COVID Relief Funding Distribution

Introduction

Senator Caryn Tyson and Representative Kristey Williams requested this audit, which the Legislative Post Audit Committee authorized at its May 5, 2021 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- What is Kansas’ process for distributing COVID relief funding?

- Have Kansas’ distributions of COVID relief funding been appropriate?

The scope of our work included examining the distribution process for CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act funding. Additionally, we evaluated a sample of CARES Act expenditures made in 42 Kansas counties.

To answer Question 1, we reviewed state and federal documents related to federal COVID relief funds the state has received since March 2020. We also reviewed state documents and talked with Office of Recovery staff and SPARK taskforce members about how the state distributed federal COVID relief funds.

To answer Question 2, we reviewed federal rules and other guidance about how CARES Act money could be spent. We also selected a sample of 78 CARES Act purchases, projects, and grants totaling $18 million (out of about $1 billion spent). These expenditures were made by county governments, businesses, and non-profits. We reviewed expense reports, invoices, and other documents to verify the amount of money spent, how it was spent, and whether federal rules allowed that expenditure. Our results are not projectable because we did not select the expenditures randomly.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. In this audit, we examined the Office of Recovery’s process for reviewing the allowability of state disbursements and county expenditures. We noted that the process relies more heavily on after the fact verification rather than pre-expenditure approval. Due to the tight timelines imposed by the federal government to distribute and spend funds, a more robust spending approval process may not have been feasible.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

Kansas used a special taskforce and legislative appropriations to distribute certain COVID relief funding.

Background

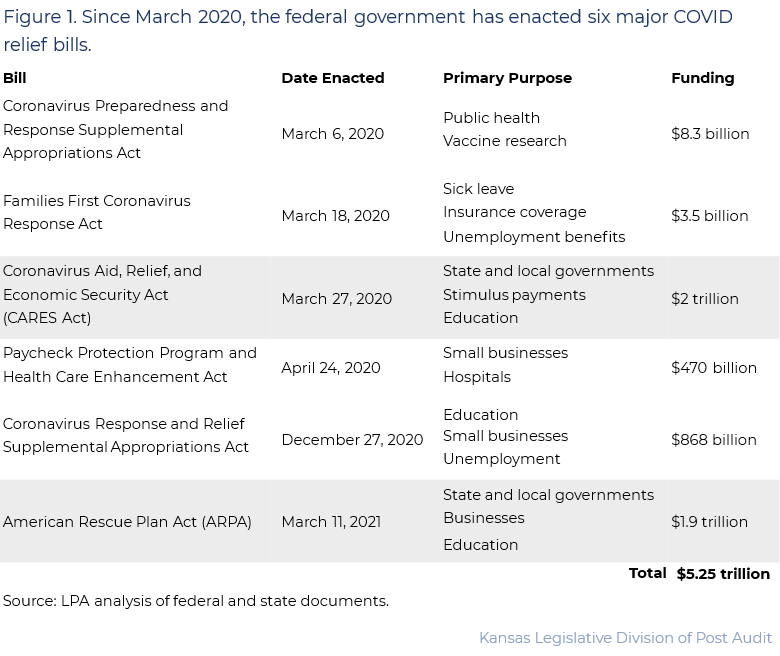

In response to the COVID pandemic, the federal government enacted six major relief bills.

- In March 2020 the federal government issued a national emergency in response to the emerging COVID-19 virus. At the same time, many state governments began closing schools and issuing stay-at-home orders.

- Due to the significant disruption in the economy and increased expenditures for COVID research and mitigation, Congress passed the first of several relief bills in early March.

- From March 2020 through March 2021, Congress enacted a total of six major laws that provided funding to federal and state agencies, local governments, and individuals. Figure 1 shows those bills and the total amount of money each one appropriated. As the figure shows, the federal government appropriated about $5.3 trillion between March 2020 and March 2021 for coronavirus relief. The CARES Act and ARPA are highlighted because most of this audit question will focus on how those funds were distributed.

Out of the nearly $34 billion the federal government allocated to Kansas, the state was given discretion on how to spend $2.6 billion.

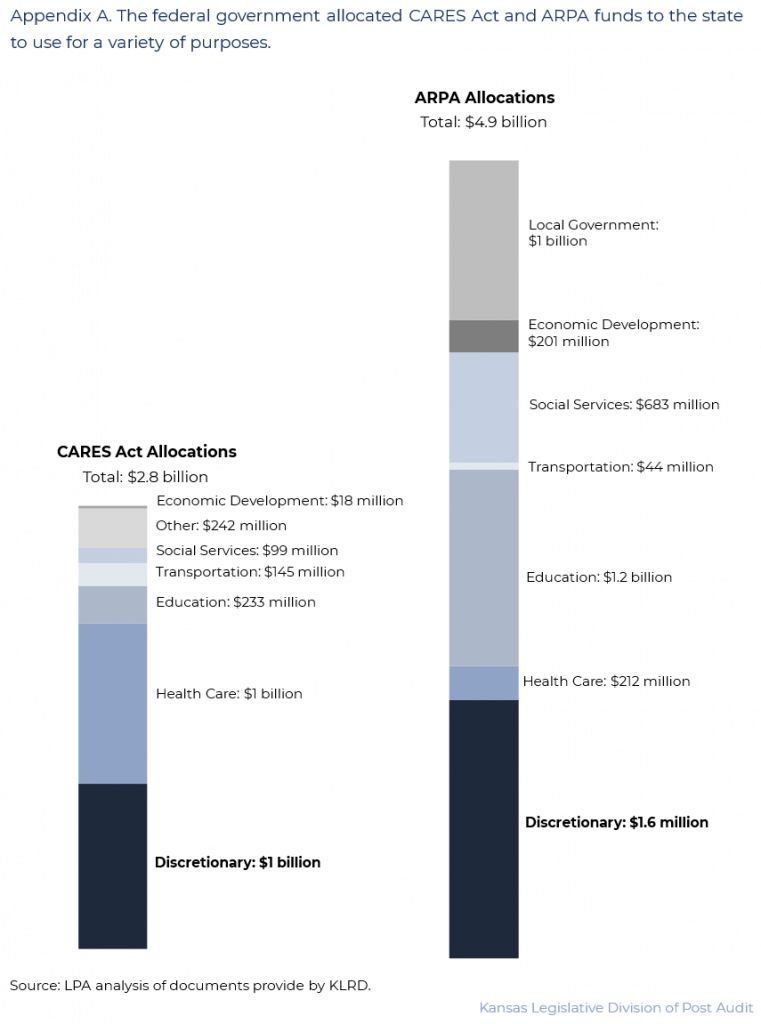

- The federal government used various methods to determine how much each state would receive. For example, the federal government distributed a portion of CARES Act funds to the states based on population. Other funds, such as those for K-12 education, were allocated based on the percentage of students who receive a free or reduced-price lunch.

- The money the federal government allocated to Kansas included both discretionary and non-discretionary funds.

- Discretionary funds were provided to the state with the expectation that the state would determine how it would be spent within some general rules. For example, some of the CARES Act funds provided money to the state to spend or distribute to local governments, businesses, or non-profits.

- Non-discretionary funds were earmarked for specific purposes set by the federal government. For example, Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds were sent to the Kansas Department of Education to be distributed to K-12 schools in the state. The state cannot re-direct those funds to other purposes.

- The federal government allocated a total of $34.2 billion to the state. Of that amount, about $2.6 billion was discretionary. The CARES Act provided about $1 billion in discretionary funds to the state to spend or distribute. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided about $1.6 billion in discretionary funds for the state to spend or distribute. Appendix A provides more information on the CARES Act and ARPA funds the federal government allocated to Kansas.

- This objective will focus on the process the state used to distribute the $2.6 billion Kansas received in CARES Act and ARPA discretionary funds. That is because these are the funds the state distributed based on its own priorities.

In May 2020, the governor established the Office of Recovery and created a taskforce to distribute and administer discretionary COVID relief funds.

- In May 2020, Governor Laura Kelly established the Office of Recovery within the Office of the Governor. The purpose of the Office is to help manage the state’s economic recovery from the pandemic and related closures. The Office is a temporary entity funded by a portion of the COVID relief funds the state received. The Office is responsible for several tasks including facilitating the work of the SPARK taskforce, managing the state’s COVID funding, and reporting to the federal government.

- Also, in May 2020, the Governor established the Strengthening People and Revitalizing Kansas (SPARK) taskforce. The initial purpose of the taskforce was to make recommendations on how to distribute the $1 billion in CARES Act discretionary funds the state received from the federal government. In June 2021, the governor announced that the taskforce would also oversee the distribution of the state’s $1.6 billion in discretionary ARPA funds.

- The SPARK taskforce has changed in membership over the last two years:

- The initial SPARK taskforce that distributed $1 billion in CARES Act money included a 5-member executive committee and a 15-member steering committee. The steering committee was divided into 3 subcommittees. The governor appointed members who included legislators, agency heads, and private businesspeople.

- The SPARK taskforce that is currently distributing the $1.6 billion in ARPA funds includes a 7-member executive committee and 4 advisory panels. During the 2021 session, the legislature passed legislation requiring that the executive committee be composed of 3 members appointed by the governor, 2 by the Speaker of the House, and 2 by the President of the Senate. Each advisory panel is composed of about 10 members appointed by the executive committee. Members include people such as legislators, business people, and educators.

The federal government permits discretionary funds from CARES Act and ARPA to be used for a wide variety of purposes.

- Kansas had broad discretion in how it distributed about $1 billion in discretionary CARES Act funds. The federal government recommended that the state share its funds with local governments. Additionally, the federal government set 3 main criteria for how the funds could be spent. Any funds spent by the state, counties, or other recipients must be spent according to these rules:

- Funds must be spent on necessary expenditures incurred due to COVID-19.

- The expenditure had to be incurred between March 1, 2020 and December 31, 2021.

- The item must not have been budgeted for prior to March 27, 2020.

- Some examples of allowable discretionary CARES Act expenditures include COVID-related expenses of public hospitals, reimbursing the cost of business closures, or improving telework capabilities. States or other recipients could not spend funds on the state’s share of Medicaid, damages covered by insurance, or payroll for those not substantially involved in the COVID health emergency.

- Kansas also has discretion in how it distributes about $1.6 billion in ARPA funds. The state and any recipients may use ARPA funds if the costs were incurred between March 3, 2021 and December 31, 2024 and meet a need in 1 of 4 categories:

- responding to the COVID public health emergency or its negative economic impacts

- premium pay or grants to essential workers

- government services that suffered from reduced revenue due to COVID

- investments in water, sewer, or broadband infrastructure

- Some examples of allowable discretionary ARPA uses include COVID testing or contact tracing, mental health services, and wastewater treatment improvements. The state may not use these funds for deposits into pension systems, to offset tax revenue reductions, or for debt service.

CARES Act Distribution ($1 billion from June 2020 to September 2020)

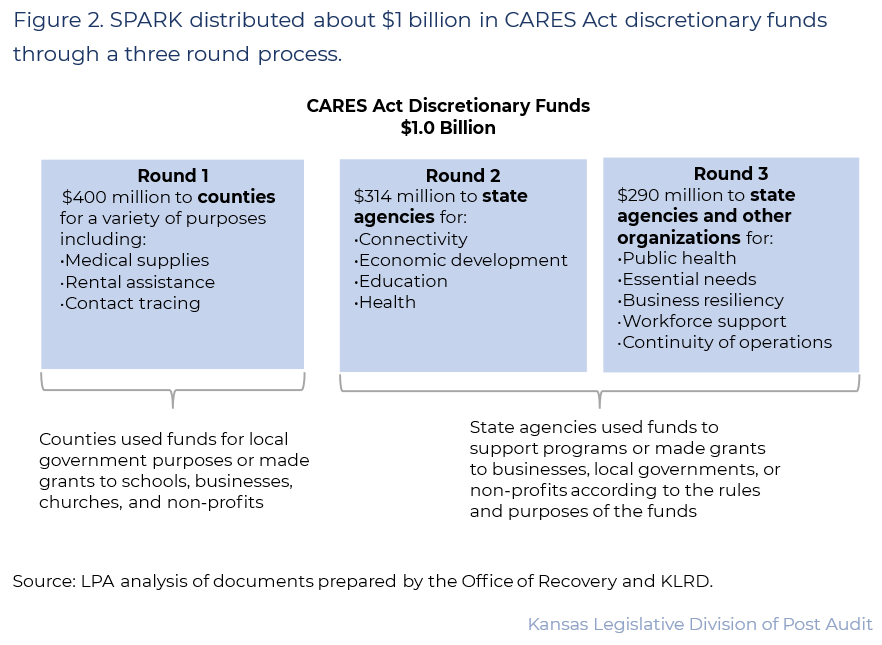

The state distributed CARES Act discretionary funding through a three round process that involved the SPARK taskforce and the State Finance Council.

- In 2020, the SPARK taskforce recommended a three-round process for distributing the $1 billion in discretionary CARES Act funds the state received. The State Finance Council approved that process. The State Finance Council includes the governor and 8 legislators. The Council approves various state activities such as settlement payments and the sale of state property. Figure 2 shows how SPARK allocated CARES Act discretionary funds. As the figure shows, the SPARK committee distributed funds in 3 rounds.

- In round 1 (June 2020), SPARK allocated $400 million to county governments. To be eligible to receive those funds, the county had to sign a resolution committing to various things, such as adhering to guidance from the US Department of Treasury and sharing with other entities in an equitable manner. All 105 counties received funds either from SPARK or directly from the federal government. The counties were responsible for deciding how to spend the funds they received.

- SPARK distributed $350 million to 103 counties that did not receive a direct allocation from the federal government. Sedgwick and Johnson counties received funds directly from the federal government because they have populations greater than 500,000. The 103 counties that received money through SPARK each received $194 per person. The SPARK committee decided on this number because it equaled the amount (on a per head basis) that the federal government sent to Johnson and Sedgwick County directly.

- SPARK distributed $50 million based on counties’ unemployment rates and COVID case rates as of June 2020. Counties with higher than average unemployment and COVID counts received this additional money.

- In round 2 (August 2020), the SPARK committee distributed about $314 million to state agencies for projects related to public health, education, connectivity, and economic development. SPARK set general funding limits for each area. Agencies created proposals for how the funds could be spent. The SPARK committee voted on the proposals based on which needs were the most pressing and cost-effective. They then sent the proposals to the State Finance Council for final approval. Five agencies were awarded funds, including the Departments of Commerce, Aging and Disability Services, Agriculture, Health and Environment, and the Adjutant General. The agencies used funds to support agency programs or to distribute to businesses, non-profits, or local governments.

- In round 3 (September 2020), SPARK allocated the remaining $290 million to organizations to spend for essential needs and services, business resiliency and workforce support, and public health. SPARK recommended funding for these areas and the State Finance Council made the final approval.

- $260 million was allocated to several organizations including the Department of Labor, the Kansas Children’s Cabinet, and the Kansas Housing Resource Corporation. Projects approved for funding included grants for small businesses, rental assistance, and funds for adult care homes.

- $30 million was allocated for state agency operations and projects. Thirty-five agencies applied for one or both of these types of funding. The Division of Budget and the Office of Recovery reviewed the applications and made the final funding decisions.

- Based on our analysis of Office of Recovery data, counties received an average of $328 per person. Figure 3 shows the amount in total and per capita that each county received. As the figure shows, the per capita amount ranged significantly across the counties from $220 (Elk County) to $930 (Chase County). In the data, funds were attributed to counties in two ways:

- Round 1 funding is attributed to the county government that received those funds. For example, SPARK allocated about $37 million to Shawnee County and all of that money is attributed to Shawnee County. All funds that counties received are accounted for in the dataset.

- Round 2 and 3 funding is attributed to the county where the business, non-profit, or local government that received it is located. For example, the Attica Meat Locker received $100,000 in grant money from the Department of Agriculture. That business is located in Harper County so the funding is attributed to Harper County. About $295 million is not accounted for because it cannot be attributed to one specific county.

ARPA Distribution ($1.6 billion from April 2021 – current)

About $1.6 billion in ARPA funds are currently being distributed through legislative appropriation and the SPARK taskforce.

- The state received $1.6 billion in discretionary ARPA funds to allocate to state agencies and other organizations. Kansas counties, cities, and towns also received funds through ARPA but the federal government distributed that funding directly to them. This section will only address those funds that the state received and distributed.

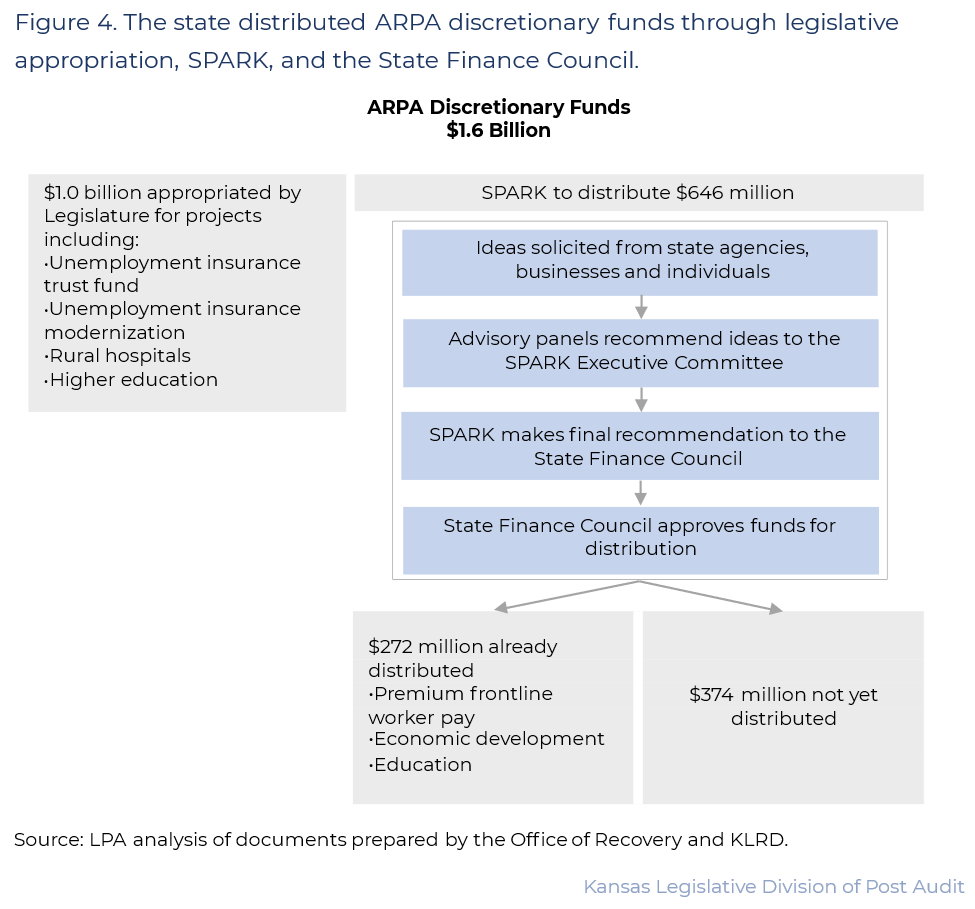

- Figure 4 shows how the state is distributing discretionary ARPA funds. As the figure shows, the Kansas Legislature appropriated about $1.0 billion of the state’s $1.6 billion in discretionary ARPA funds.

- In 2021, the legislature appropriated about $617 million for several projects including the state’s unemployment insurance fund, rural hospital grants, and a crisis hotline.

- In 2022, the legislature appropriated an additional $419 million for items such as higher education, nursing facilities, and housing grants.

- In 2021, SPARK distributed about $272 million to several projects to address immediate needs created by the pandemic. Those projects included increased pay for frontline care workers, economic development, and education.

- In January 2022, SPARK solicited investment ideas from state agencies, county governments, businesses, and individuals for how to spend the remaining $374 million. Interested entities could submit an idea through an online submission form. SPARK received over 800 suggestions. A few included:

- Premium pay for essential workers

- HVAC replacement for the Topeka Performing Arts Center

- Computer replacement at the Kansas Bureau of Investigation

- Radio system upgrade the Marysville Police Department

- There are currently 4 SPARK advisory panels, consisting of about 10 members each, to evaluate spending ideas. The panels include subject matter experts, business leaders, legislators, and staff from state agencies. The panels identified priorities and filtered the ideas down to about 100. The panel then identified high priority submissions based on criteria such as allowability, whether other funding already existed, feasibility, and whether the project will have a high impact. Each advisory panel recommended submissions and a funding amount to the SPARK executive committee. The SPARK executive committee will evaluate these submissions and and make recommendations to the State Finance Council for approval. However, SPARK has not yet done so as of the writing of this report.

The state’s distribution of CARES Act funding appears appropriate but some spending may be problematic.

We evaluated the state’s CARES Act funds distribution process and a sample of CARES Act expenditures.

- We evaluated the state’s process for distributing CARES Act funds. We reviewed policy and guidance documents and talked with staff at the Office of Recovery. We reviewed federal documents to understand the rules for distributing funds. We also spoke with several SPARK members to get their opinions on the process and if anything could be improved.

- We focused on CARES Act discretionary spending because it was at high risk of waste. This is because the federal government required the money to be spent quickly or the entity would lose the money. The pressure of “use it or lose it” increased the risk that money would be spent in wasteful or unnecessary ways. Additionally, legislators expressed concerns about how the funds were spent. For these reasons, we evaluated spending in more detail.

- To evaluate spending we took several steps:

- We selected a sample of about $18 million (out of $1 billion) in CARES Act discretionary spending. We chose these expenditures because based on a brief description of the expenditure it appeared high risk. In some cases, the state’s consultant flagged the expenditure during its preliminary review. In other cases, the expenditure seemed unusual on its face or appeared excessive. Our results are not projectable because we did not choose expenditures randomly.

- We reviewed the expenditures for allowability under federal rules. To do this, we reviewed federal rules and guidance documents. We talked with county staff and business owners to understand what they spent the money on and why. We reviewed expenditure reports, invoices, and other documents. In a couple instances, we observed land and buildings that were purchased with CARES Act funds.

- We also reviewed spending to make sure that the expenditure seemed reasonable. We did this because federal allowability rules are extremely broad and nearly all expenditures were likely to be allowable. Further, we identified some problems with federal rules that increased the risk that funds could be spent in unreasonable ways. Due to these issues, it was likely that even allowable expenditures could be problematic for other reasons.

- We did not evaluate ARPA distributions or spending for two reasons. First, ARPA distributions and spending were still ongoing at the time that we conducted this audit. Second, much of the distributions were made through legislative appropriations. To maintain the professional independence of this office, it would be improper for us to review the appropriateness of the Legislature’s choices.

CARES Act Distribution

The state’s distribution of CARES Act funding appeared appropriate and reasonable.

- The federal government gave broad discretion to states in how to distribute certain CARES Act funds. The federal government recommended states share a portion of its funds with local governments. Outside of that, each state could set its own priorities and disburse the funds in accordance with them.

- The state’s process for distributing the money appeared appropriate because:

- It involved people from a variety of backgrounds including business, legal, and legislative. It involved people from a variety of industries including banking, aerospace, and farming. The SPARK committee also sought the input of subject matter experts at state agencies and educational institutions.

- The SPARK committee considered spending allowability while making distribution decisions. The Office of Recovery used a consultant to review certain proposals to make sure they were allowable before approving them. Further, the Office provided training to county and agency officials to ensure that they understood what types of spending were allowable.

- The county distribution method was logical and fair. Counties were allocated a per person amount based on what the federal government sent Johnson and Sedgwick counties. Further, additional money was allocated based on COVID counts and unemployment rates.

- We reviewed the broad categories of funds that SPARK distributed for allowability and did not identify any concerns. However, federal allowability rules are for actual spending, not the distribution. The state may distribute money to a program that appears allowable. If the recipient spends funds on something that is not allowable, they may have to return the money to the federal government.

- We talked to several CARES Act SPARK members. They thought the distribution decision process went well although many noted that it was rushed. Most members we spoke with had only minor suggestions on how to improve the process. Those included suggestions such as reducing the layers of review or including more business stakeholders. However, none of the suggestions were mentioned consistently to indicate a systemic concern.

CARES Act Spending

Although SPARK distributed funds, it was the responsibility of counties and agencies to ensure those funds were spent appropriately.

- Counties that received CARES Act discretionary funds could either spend the money for local government operations or make grants to other organizations. Each county could set its own process for making those decisions. Some counties we talked with told us they set up special committees to determine how they would spend the money. Others hired consultants to assist them.

- It is the responsibility of the counties to make sure the funds they distributed were spent appropriately. The majority of the 35 counties we talked with reported that they reimbursed expenditures only after the organization submitted receipts. A few counties mentioned they required subrecipients to sign an MOU with the county to ensure that the organization understood how they could use the money.

- State agencies that received funds to distribute to other organizations were responsible for monitoring those expenditures. Agencies required sub-recipients to sign MOUs to ensure the recipients understood how they could spend their funds. Further, agencies worked with the Office of Recovery to make sure the agency monitoring process was adequate. It was then the agencies’ responsibility to make sure funds were spent appropriately.

- Due to time constraints we were not able to assess the effectiveness of the different processes the counties and agencies used to monitor those funds. Instead, because the funds were at high risk of waste, we focused on the actual spending of the funds, as described in the next section.

Most CARES Act expenditures we reviewed were likely allowable under federal spending rules.

- We reviewed 78 CARES Act purchases, grants, or projects totaling about $18 million to determine if federal rules allowed them. When counties made grants, we reviewed the purpose of the grant and accounted for the funds it disbursed. We reviewed expenditures made in 42 Kansas counties. Additionally, a few of the purchases or projects we reviewed were made by private organizations under grants made by state agencies.

- In some cases, a purchase included just a single expenditure. For example, if the county purchased a vehicle. In other cases, a project might include many expenditures. For example, if a county distributed funds to upgrade a community kitchen, that could include a dozen different expenditures (i.e. a new refrigerator, construction work, etc.) In these cases, we reviewed all the expenditures associated with the project.

- To determine if an expenditure was allowable we followed federal guidance. The federal government allowed CARES Act funds to be spent on activities or items that were necessary to address the COVID emergency. The expenditure must have been incurred between March 1, 2020 and December 31, 2021. Further, the item must not have been budgeted for prior to March 27, 2020. Last, although we consulted federal guidance, this is our assessment of allowability. Ultimately, the federal government will determine whether an expenditure is allowable or not.

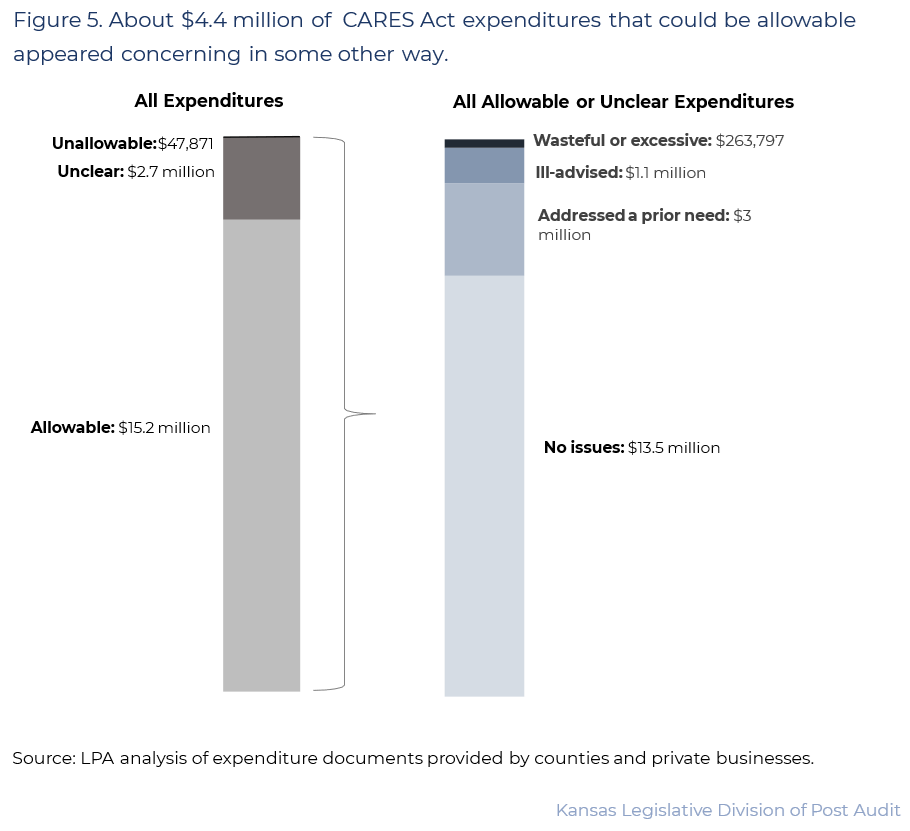

- About 85% ($15.2 million) of the expenditures we reviewed appeared clearly allowable under federal rules. This was because it appeared to directly address a COVID related need. Some of the types of spending we thought were allowable included food supplies for food pantries, personal protective equipment, equipment to increase meat processing capacity, and funds to pay for COVID-related sick leave. For each of these expenditures, the need and connection to the COVID emergency was clear.

- The allowability of 15% ($2.7 million) of the spending we reviewed was unclear. This was because the federal allowability rules were extremely broad. Some of the expenditures in this category included electronic signs, security systems, and teacher salaries. In these cases, the connection to a COVID-related necessity was less clear to us. For example, one county spent $218,000 on large electronic signs that could be placed at the border of each town in the county. Officials told us they could convey COVID-related messages on them. Whether this represents a necessary expenditure related to the COVID-emergency is debatable. While we think this type of spending might be allowable, we cannot be sure how the federal government will view it.

- Less than 1% (about $48,000) of the expenditures were likely unallowable under federal rules because they did not appear necessary to address the COVID-emergency. In these cases, there was no clear connection to the COVID-emergency. For example, one county used its funds to buy flu vaccines. Another county spent funds on donuts, pastries, and coffee for meetings. About $4,700 was unallowable because the organization incurred the costs in February 2020 which was before the allowable time frame of March 1, 2020. CARES Act money that is spent in ways the federal government does not allow must be paid back to the federal government.

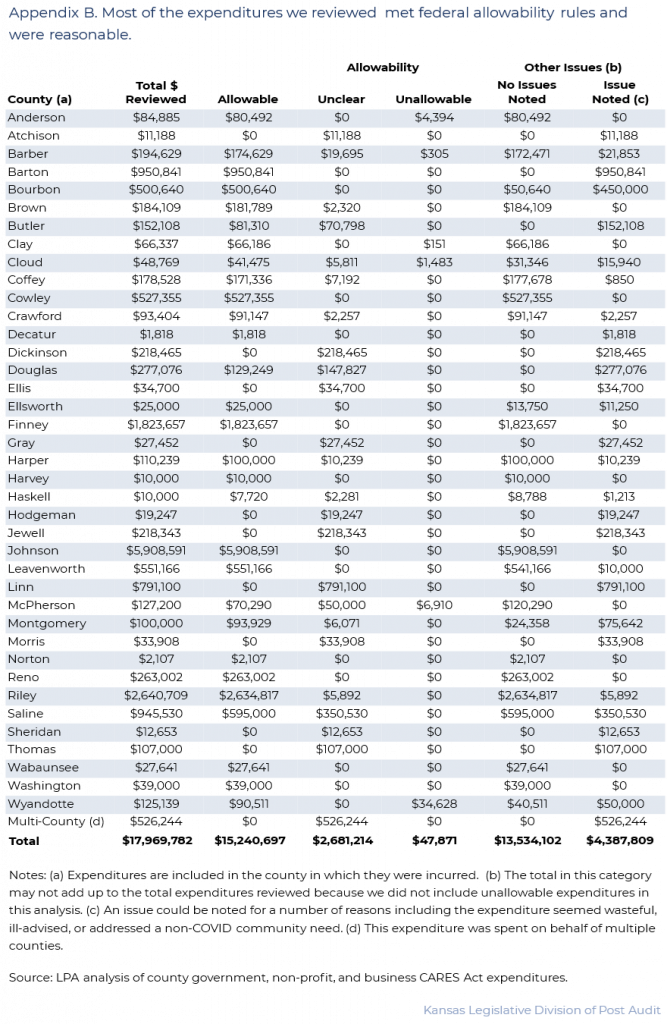

- We were not always able to evaluate whether the spending had been previously budgeted for. Federal rules do not allow CARES Act money to be spent on items that were budgeted for prior to March 27, 2020. In other words, the CARES act funds were not to be used for anticipated normal operations. Most expenditures we reviewed obviously were not budgeted prior to that deadline because there was no need for those items prior to March 2020. For example, masks, large quantities of hand sanitizer, or plexiglass panels. However, for some expenditures we lacked the time to review county budgets to determine if and when the county budgeted for the item. Appendix B provides more information on the expenditures we reviewed.

Although most expenditures we reviewed were likely allowable, some expenditures appeared wasteful or raised other concerns.

- During our review we noted a number of expenditures that might be allowable but raised other concerns. In some cases, the expenditure seemed wasteful. In other cases, it seemed ill-advised or the expenditure addressed a problem that existed prior to COVID. Given the broad nature of federal allowability rules, most expenditures were likely to be allowable. However, an allowable expenditure might not be a reasonable or prudent one.

- Figure 5 shows the results of our additional review of expenditures. As the figure shows, 76% ($13.5 million) of the expenditures we reviewed seemed reasonable. They included items such as personal protective equipment, supplies for food pantries, grants to small businesses, and equipment to enable work from home. These expenditures did not appear wasteful or excessive. Further, they seemed like a reasonable and prudent use of funds meant to address COVID-related necessities.

- About 17% ($3.0 million) were expenditures that appear to have addressed a need that existed prior to COVID. These expenditures did not appear wasteful and often addressed a community-wide need. For example, one county spent about $218,000 to add showers to a community emergency shelter. County officials told us they identified the lack of showers as a problem during previous uses of the shelter. The building has not, so far, been used as a shelter for COVID-related reasons. Installing showers likely improves its function as a shelter for any future use. Although an upgraded shelter is likely useful to the community, the need for it was unrelated to COVID.

- About 6% ($1.1 million) of the expenditures appeared ill-advised. These expenditures often did not appear cost effective or seemed counterproductive. For example, one county spent $450,000 to start a new grocery store in an underserved part of town. The store lasted only a few months. The consultant that reviewed the proposal flagged it as “high-risk” because its necessity was not clear and it did not appear feasible. County officials told us there were concerns about it but went forward with the project anyway. In another case, a recipient that received a small business grant spent $20,000 to help the community put on a local festival. Expenditures encouraging mass gatherings during a pandemic seem contrary to the efforts to contain the spread of COVID.

- About 1% ($264,000) of the expenditures appeared wasteful or excessive. We identified expenditures for electronic signs, sports equipment, lanyards, and excessive office supplies. For example, one grant recipient spent a third of its $2,500 grant on chalkboards, a blowup tube man, and electronic LED signs for advertising. The grant was meant to purchase food for a food pantry.

We also reviewed expenditures for a few other issues but did not find any serious concerns.

- We reviewed expenditures to determine whether the expenditure may result in long-term costs to the state. We found only 1 expenditure that could result in a small ongoing cost to the state. In that case, the school district used funding to pay for a portion of an additional PE teacher’s salary. Because the state pays the school district’s portion of KPERS, this will result in a cost to the state.

- About half of the expenditures were not the original planned amount. In many cases this was because the planned amount was only an estimate. When the county spent more than planned, it often used other funds to cover the overage. When a county spent less, they often told us they distributed the difference to other projects.

- In a few instances, the county did not spend the planned amount at all. This was usually because it decided the project was not a priority or were concerned about allowability. For example, one county decided spending $26,000 on a movie theater was not a priority. The county told us they re-allocated that money to other projects. Another county originally planned to build a new community building. However, consultants raised concerns about necessity and feasibility. The county decided to not fund the project at all.

- In 2 instances, we were not able to review a recipient’s expenditures at all. This was because the recipient failed to submit documentation by the deadline.

Federal rules likely contributed to many of the problems we encountered.

- At the state level, the quick distribution and spending timeframe reduced the ability to thoroughly review requests. Kansas counties received their funds from July 2020 through September 2020. The initial federal rules required money to be spent by December 30, 2020. Although the federal government extended the spending deadline by another year in December 2020, most counties had already allocated or spent the funds.

- The tight time frame meant the state did not have sufficient time to require prior approval before the funds were spent. As a result, most of the state’s activities have focused on monitoring expenditures after they were made rather than approving them before they were made.

- The Office of Recovery provided guidance but did not approve purchases or projects prior to the expenditure. The Office provided training, guidance, and technical assistance to counties to help them understand what was allowable. It required counties to sign resolutions indicating they understood the purpose of the funds. Additionally, the Office required counties to submit a spending plan to consultants for review. However, the consultants did not approve those expenditures either. They provided guidance to counties and gave advice on the potential allowability of expenditures.

- The Office of Recovery’s most in-depth review has occurred after recipients spent the funds. Counties are required to submit monthly expenditure reports. Office of Recovery staff review those reports for compliance with federal allowability rules. Additionally, agencies that make grants are required to submit expenditure reports and are expected to monitor recipients’ expenditures.

- The counties did not have time to fully assess their needs. In some cases, county officials said they had a need but did not actually evaluate it. For example, one county told us they thought the county may have greater mental health needs due to COVID. However, they did not have time to fully evaluate what those needs were. The faster an organization has to spend money, the less likely they are to make informed decisions.

- “Use it or lose it” rules for spending may incentivize wasteful spending. Any funds a recipient did not use would revert to the state. Any funds the state did not use would return to the federal government. Often, recipients may decide to spend money on something that may not be very defensible, rather than lose it. This can result in wasteful and unnecessary spending.

- Federal spending allowability rules were extremely broad. Largely, any expenditure considered necessary due to the COVID public health emergency was allowable. The broad and poorly defined nature of “necessary” leaves a lot of gray area. This increases the likelihood that recipients will spend money in ways not truly intended.

- Last, Federal rules for CARES Act discretionary spending do not require any performance metrics. Recipients were not required to prove they met the goals they said they would when they received the funds. Further, there are no requirements to repay the money if the project is unsuccessful. For example, one county spent $450,00 to open a new grocery store. The store opened in January 2021 but closed in May 2021. Because there were no requirements for the store to remain open for any particular length of time, the quick failure is unlikely to result in the county having to pay any of the money back. Clear goals that must be met can help counties focus their spending on projects that are likely to be successful. Without them, they may be less careful and inadvertently waste money.

Other findings

The Office of Recovery operates a fraud, waste, and abuse hotline but does not directly investigate fraud allegations.

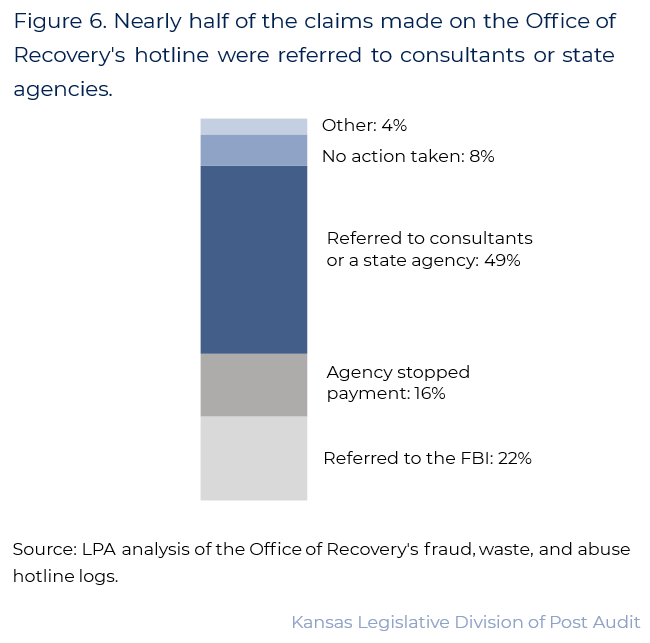

- In June 2020, the Office of Recovery set up a fraud, waste, and abuse hotline. We reviewed the log of complaints the office maintained. At the time that we reviewed the log, there were 73 complaints. The general public made most (47) of those complaints. State agency officials could also report concerns to the office. They reported 26 issues.

- Office of Recovery staff told us they maintain the hotline but do not conduct fraud investigations. Staff reported they log claims and evaluate whether they are related to fraud, waste, and abuse. They also refer confirmed issues to consultants, state agencies, or the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). They have not been tasked with conducting fraud investigations themselves.

- Figure 6 shows what actions the Office of Recovery took for the 73 claims. As the figure shows, many claims (49%) were referred to consultants or state agencies. The state’s consultant told us they only check to make sure the paperwork is complete and accurate but do not conduct fraud investigations. State agencies can sometimes resolve issues because they have additional information but they do not conduct fraud investigations either. However, 22% of the claims were referred to the FBI for further investigation.

- For some of the allegations we reviewed, it would be difficult to conduct any sort of investigation. This was because some were reported anonymously and the reporter did not provide enough information to investigate the claim. Additionally, some claims were not actionable. For example, one person claimed that the county had committed a fraud because they had not received any CARES Act money. This person reported that the county received $194 per person but the caller had not received any funds personally. That was likely a misunderstanding about the distribution of the funds. A fraud investigation was not necessary in this case but someone from the governor’s office reached out to the individual to alleviate the concern.

Conclusion

We did not draw any conclusions beyond the findings already presented in the audit.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On August 15, 2022 we provided the draft audit report to the Office of Recovery. Its response is below. Agency officials generally agreed with many of our findings and conclusions. However, they disagreed with how we characterized some of the CARES Act expenditures we reviewed. We agree with the Office that many of the specific examples we noted are likely to be allowable under the federal guidance. As stated in the report, the federal rules required funds to be spent very quickly and the rules were often overly broad. However, some expenditures were concerning to us for other reasons. The examples we provided were expenditures that may be allowable but still seemed questionable.

Office of Recovery Response

Office of Recovery Response to LPA Report on COVID Relief Funding Distribution

The State of Kansas has received billions of dollars in federal funding in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on Kansas. The Kansas Office of Recovery (RO) was established by Governor Laura Kelly in May of 2020 to manage and administer federal COVID relief funds as the state began its response to the pandemic.

Since then, the RO has assisted in the distribution and management of billions of dollars of relief funding to local governments, state agencies, businesses, non-profits, and other entities with an emphasis on transparency, equity, and accountability.

Guidelines for these relief funds were set by the federal government through guidance documents from the U.S. Department of Treasury, and spending in Kansas was done according to processes set out in Kansas legislation passed in the 2020 and 2021 legislative sessions.

While the RO generally agrees with the conclusions of the LPA report, the report takes a narrow view of the allowability and “reasonableness” of certain relief fund expenditures that does not take in to account the full scope of the pandemic situation as it existed at the time funding decisions were being made. Additionally, some of the characterizations of the compliance support utilized by the RO and of the Office’s Fraud, Waste, and Abuse procedures have been mischaracterized or otherwise not presented with full context. The RO disagrees with some of the conclusions of the Legislative Post Audit and will provide additional context regarding these conclusions in this response.

The RO does not seek to respond on behalf of the federal government or local governments. Our response will focus on the RO’s role in the process, which is to ensure compliance and allowability for all expenditures.

RO Compliance Support

As stated in the report, it was the responsibility of CRF recipients to ensure funds were spent appropriately. However, the RO provided significant guidance, resources, and technical support to both counties and state agencies to assist with compliance and allowability for use of funds.

All counties were required to submit monthly CRF expenditure reports, which were reviewed by RO staff. Any issues or concerns identified in the expenditure reports were then communicated to the counties to make necessary changes. These changes could include determining if additional information about the expenditure could address the issue and, potentially, identifying alternate eligible expenses the funding could be reallocated towards. Counties were then required to submit an updated monthly report reflecting any changes along with a change log highlighting the items addressed.

State agencies receiving CRF were also required to submit CRF expense reports to the RO. These reports were reviewed by the RO for compliance and documentation. Similar to the county process, the RO provided assistance to state agencies to identify alternate eligible expenditures, submit change logs, and update reports when necessary.

The RO utilized contracted subject matter expert consultants to assist in the development of compliance materials, technical review of CRF expenditures and reports, communication with CRF recipients, and general compliance. These expert consultants work alongside RO staff and are directly managed by RO leadership. Because of this the consultant support team is considered an extension of RO staff.

One of the reasons the RO utilizes these consultants is their strong expertise on federal allowability and the administration of federal relief dollars. The complexity and timeline for allocating and expending federal relief funds necessitated the expertise provided by these consultants.

The consulting firms the RO contracts with work with multiple states/entities beyond Kansas and are in regular contact with the US Treasury regarding federal guidance on allowability and use of funds. The US Treasury has the final authority on the allowability of relief fund expenditures. The unique perspective provided by the subject matter expert consultants puts Kansas in a strong position to defend the eligibility determinations and use of funds for both CRF and SFRF expenditures.

As acknowledged in the audit, federal allowability for CRF and SFRF is a complicated area that evolved over the course of the pandemic. Relief fund recipients had to make timely decisions around how to use funds to meet the immediate needs of their communities given the best information available to them at the time, and as such funding decisions should be considered in that context when evaluated in hindsight. It should be noted the RO leveraged the benefits of webinars and direct consultation with Treasury staff, as well as the above stated expertise of the consultant support team to provide a deeper, real-time understanding of federal requirements.

Reasonableness of CRF Expenditures

As stated above, the RO’s role is to administer funds in accordance with federal guidelines and state law. Operationally, that means the RO coordinates with the entities that implement the programs funded with federal relief dollars. Decisions on spending are made through the SPARK committee with final approval made by the State Finance Council. In calendar year 2020, $400 million CRF was distributed directly to local governments, who had the ability to determine what was needed in their communities.

This local CRF spending was directed by local elected officials, in accordance with the concept of local control. It should be noted that in order to receive these funds, local governments agreed to resolutions stating that they understood federal requirements for use of CRF and would abide by them. Per these resolutions the local governments themselves would ultimately be responsible for returning any CRF dollars used for ineligible expenses to the federal government.

The RO served to ensure that federal allowability guidelines were being followed. Therefore, the RO would like to provide some additional context around the allowability of CRF expenditures identified in the report as “unreasonable.”

The US Treasury provided guidance to state governments on the allowability and eligibility of expenses. “Reasonableness” as used within this report was not a term identified or defined by the Treasury. In making allowability and eligibility determinations the RO relied on the guidance issued by the Treasury for CRF as established by Congress through the CARES Act. Using this guidance, the RO identified expenditures into one of two categories: allowable or unallowable.

The reasonableness of the following local CRF expenditures is questioned by LPA in the report. Included below is additional context around these expenditures based on the RO’s understanding of federal allowability:

- “For example, one county spent $218,000 to install large electronic signs at the border of each town in the county.“ – Large electronic sign boards are a traditional response by EMS and other first responders to an emergency. What made the COVID pandemic unique was the lack of availability of these resources. Normally first responders borrow needed sign boards from their transportation department or from the state. Because the pandemic was not an isolated event like a tornado, fire, or flood, every jurisdiction including the state was utilizing these sign boards at the exact same time. The sign boards were being used to coordinate testing locations or make the community aware of other COVID related updates. For a county to make a determination that the sign boards were a valid investment related to COVID and could not rely on the traditional practice of borrowing these resources would be allowable given the conditions on the ground at the time.

- “For example, one county used its funds to buy a plastic “tube man” to advertise a food pantry.“ – Food scarcity was a very real issue during the early days of the pandemic as restaurants, grocery stores, and convenience stores were either closed, had scaled back operations, or were experiencing supply chain disruptions. Additionally, many individuals were furloughed or lost their jobs. Communities saw a sharp increase in the number of individuals that needed to utilize services such as food banks and pantries for the first time. Many communities used communication strategies and marketing techniques like a “tube man,” which would be an allowable expenditure, to inform the public about the availability of these resources.

- “Another county spent funds on donuts, pastries, and coffee for meetings.” –Many restaurants and convenience stores were experiencing operating issues at this time due to the pandemic. At this time in-person meetings were rare to begin with but to expect attendees to be able to stop on the way to a meeting and/or leave the meeting during breaks to get refreshments was not realistic. All efforts were being made to reduce the size of groups, limit unnecessary exposure, and provide resources to critical employees during the pandemic. Having basic refreshments available for critical front-line staff for an in-person meeting during the pandemic would be allowable given the proper context.

- “For example, one county spent almost $225,000 to add showers to a community emergency shelter.” – The criticism of this expense is that the shelter was never activated for COVID. At the time local and state governments were being told by public health officials to plan for the worst and thus upgrading an existing emergency shelter to be ready to be used for congregate housing or some other pandemic related purpose was an entirely valid investment. There are examples from across the country of temporary shelters being established, field hospitals being erected, and defibrillators and other medical equipment being procured. The fact that these resources were not activated for COVID response does not take away from a local government‘s proactive preparations to respond to the pandemic.

- “For example, one county spent $450,000 to start a new grocery store in an underserved part of town.” – Information provided by local leaders suggested they felt that investing in a grocery store would not only provide access to critical food resources in a known community food desert but also would provide jobs and hopefully help jumpstart the economy of a part of town that was disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. Economic development to aid the response and recovery from the COVID pandemic was deemed an allowable use of relief funds. This concept of serving disproportionately impacted individuals and communities became a signature component of subsequent Treasury funding.

- “$20,000 to help communities put on a local festival.” – As public health officials started to signal the all clear and a return to the “new-normal,” it was a priority of many local leaders to jump start their local economies and provide economic opportunities to local businesses. Providing support for an outdoor local festival was a strategy that many communities across the country employed as residents were still leery of returning to more traditional brick and mortar stores. These festivals also provided an opportunity for local leaders to distribute information about available resources including testing and vaccine options.

- “For example, one grant recipient spent a third of its $2,500 grant on chalkboards, markers, and electronic LED signs for advertising. The grant was meant to purchase food for a food pantry.” – The marketing component related to addressing food scarcity has already been touched upon but even a simple expenditure like office supplies needs to be viewed through the context of the pandemic. Efforts to mitigate disease transmission were paramount during the pandemic. Common office items like markers, staplers, tape dispensers, that were always shared were viewed as a potential opportunity for contamination and spread of the disease early in the pandemic. Thus, employers were forced to invest in additional resources like office supplies so each employee had their own if working in-person, or to send with the employee if working virtually.

There was also one example included in the report of expenditures occurring prior to March 2020. The RO concurs that any CRF expense prior to March 2020 would be unallowable. These expenditures were not reported by the jurisdiction in their required reporting to the RO and the RO does not have a record of these expenditures. If LPA could provide additional information about the jurisdiction and the transaction, the RO will follow-up on that item.

Fraud, Waste, and Abuse Process

The Office of Recovery works to prevent fraud, waste and abuse in the solicitation and use of Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) and State Fiscal Recovery Funds (SFRF) funds. The RO established robust policies and procedures to detect and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. This primarily occurs through agency training and support and preliminary investigations for claims of fraud, waste, or abuse reported to the Office.

Any individual can submit a report of fraud, waste, or abuse of CRF or SFRF funds (“AFWA report”) by phone, mail, or online. The AFWA Portal is an online tool that ensures allegations are collected and investigated appropriately. This portal allows the public to report any suspected fraud, waste, or abuse of CRF funds and SFRF funds. If RO staff receive an AFWA report by phone or email, they will enter the information into the AFWA Portal.

In accordance with RO policies, each AFWA report received is reviewed by RO staff during a preliminary investigation. The preliminary investigation includes, but is not limited to, evaluating the complaint, gathering information, and coordinating with relevant agencies. Staff then determine whether the reported conduct coincides with fraud, waste, or abuse. It should be noted that the expertise of consultant support is sometimes utilized in these preliminary investigations.

Following the evaluation and determination that the conduct coincides with fraud, waste, or abuse, the report is referred to the appropriate entities and/or authorities as either a potential criminal investigation, civil legal concern, or constituent inquiry. Once the RO makes a suspected fraud, waste, or abuse referral, it is up to the entity that received the report to make the final determination to take legal action.

If, after evaluation, staff determines that the conduct does not coincide with fraud, waste, or abuse, that determination is documented. All AFWA reports are recorded in a centralized location to ensure that allegations of fraud, waste, or abuse are adequately and consistently addressed.

In cases of potential criminal or civil legal concern, and at the direction of law enforcement or in accordance with the findings of any state legal actions, the RO may utilize one or more of the following tools to remediate fraud, waste or abuse of funds:

- Recommendation to the appropriate agency or government official to take administrative or corrective action;

- Performance of additional audits or focusing existing audit requirements on areas of concern;

- Administrative measures such as temporary or permanent ineligibility, removal from competition, withholding disbursements for payments and other similar actions; and

- Recoupment of funds from recipient.

The Office of Recovery thanks Legislative Post Audit for their work on this report and for the opportunity to submit this response.

Appendix A – Federal Allocations

This appendix provides additional information on the CARES Act and ARPA funds allocated to the state by the federal government.

Appendix B – Expenditure Details

This appendix provides additional details about the CARES Act expenditures we reviewed. Expenditures are accounted for in the county where the recipient is located. Additionally, recipients could be local governments, private businesses, or non-profits.