Evaluating Whether Services to Collect Child Support Payments in Kansas are Effective and Timely

Introduction

The Senate Ways and Means committee requested this audit, which the Legislative Post Audit Committee authorized at its April 22, 2022, meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- Is the child support services system effective in collecting child support payments?

- Does the child support services system provide timely services and payments?

- How does Kansas’s child support services system compare to other states?

For reporting purposes, we consolidated findings from questions 1 and 2 into a single answer.

To answer these questions, we interviewed officials from the Kansas Department for Children and Families (DCF), its two contractors, and Kansas court trustees. We reviewed state law, federal law, and DCF contracts to identify relevant child support requirements. We also reviewed national child support performance reports from fiscal years 2017 through 2021. We spoke to officials from 5 other child support offices in Colorado, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, and Oregon. We also conducted interviews with parents that used DCF or court trustee child support services.

Kansas court trustees are not held to any federal or state performance and timeliness requirements. Further, there is no central database of trustee cases. Because of this, we were unable to evaluate the effectiveness and timeliness of court trustees’ child support services.

DCF’s outdated computer system also prevented us from analyzing how timely or effective DCF’s child support services are. Instead, we relied on DCF’s performance on four federal child support requirements for fiscal years 2017 through 2021. These results should be seen as general indicators of DCF’s child support performance.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. In this audit, we found that DCF lacked certain processes to quickly address delinquent child support payments. We also found DCF did not provide adequate oversight over its two child support contractors.

We couldn’t determine how effective or timely the state’s child support services system is due to data limitations, but we saw several signs it’s not working as well as it could.

Background

Federal law requires states to assist parents in collecting monthly childcare payments.

- Child support is ongoing, periodic payments that non-custodial parents make to a custodial parent. These payments are intended to provide financial support and benefits to children.

- Child support obligations typically end when a child turns 18. However, non-custodial parents are obligated to pay any unpaid amounts regardless of a child’s age. For example, if a child turns 18 but a parent has unpaid child support from prior years, that parent still owes those unpaid obligations.

- Under the federal Social Security Act, states’ welfare agencies are required to provide a public child support collection system for children receiving public assistance through certain programs (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or Medicaid). For example, if a single parent signs up for and qualifies for one of these programs, their case will be referred to the state welfare agency responsible for public child support services. Parents generally must agree to the child support services to receive those public assistance programs.

- Families can also choose to hire a private attorney although cost may deter families from doing so. Doing so largely removes them from the state’s child support system. For that reason, we didn’t evaluate private child support cases.

In Kansas, the Department for Children and Families is the primary state agency responsible for administering the state’s child support program.

- The Kansas Department for Children and Families’ (DCF) Child Support Services administers the child support program to fulfill the state’s federal requirements. DCF’s responsibilities include 2 service phases:

- Establishment involves creating a case file, locating non-custodial parents, establishing paternity, and securing a court order to compel child support payments.

- Enforcement involves monitoring child support payments and taking actions to resume compliance when child support payments become delinquent. Several tools exist to help enforce child support payments. These include modifying court orders, income withholding, offsetting state and federal tax refunds, license restrictions, property liens, and contempt orders. In most cases, enforcement begins with an attempt to issue an income withholding order and may end in contempt orders for nonpayment if withholding or other actions are unsuccessful.

- While any Kansas custodian or parent can voluntarily apply for DCF’s child support services, some parents are required to use DCF. Federal law requires DCF to provide child support services to families who receive certain public assistance even when the custodial parent is not actively seeking child support.

DCF uses 2 contractors to provide child support services.

- In 2013, DCF fully privatized child support services. Since October 1, 2021, DCF contracts with 2 companies to cover statewide services:

- Maximus Human Services provides services in 4 counties: Shawnee, Johnson, Sedgwick, and Wyandotte counties. As of February 2023, DCF reported that Maximus had about 63,000 cases or 49% of DCF’s current caseload.

- YoungWilliams provides services in all other parts of the state. As of February 2023, DCF reported that YoungWilliams had about 66,000 cases or 51% of DCF’s caseload.

- The contractors are responsible for establishing cases and enforcing payments. Specifically, they perform services such as creating case files, moving support orders and enforcement cases through the court process (including establishing paternity), and monitoring payments to ensure they are on time and paid in full.

- Although contractors carry out much of DCF’s child support duties, DCF is ultimately responsible for overseeing this process. As such, DCF is responsible for creating policies and procedures for contractors to follow, ensuring compliance with federal requirements, providing training, monitoring contractors’ performance, and enforcing contract terms.

Kansas court trustees also can provide child support services, but they generally only provide enforcement services.

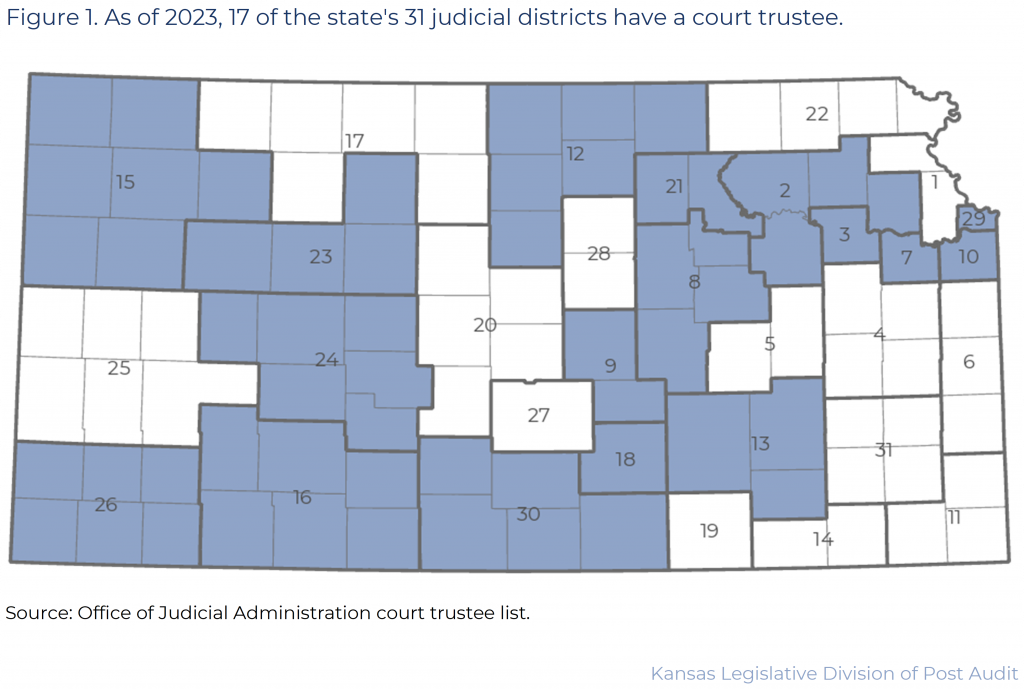

- State law (K.S.A. 20-377) established the “court trustee system” in 1972. Trustees are licensed attorneys who collect court-ordered debts and payments. In Kansas, this includes child support payments. By law, the chief judge of each of the state’s 31 judicial districts can decide to appoint a court trustee for their district. Figure 1 shows which judicial districts have a trustee. As the map shows, 17 of the state’s 31 judicial districts currently have a trustee.

- Court trustees mostly provide enforcement services. Generally, cases are only assigned to a court trustee after a child support order has been established. For this reason, it’s rare for trustees to handle cases that require things like establishing paternity. Trustees’ primary responsibility is to help ensure court ordered debts and payments are made on time and in full.

- The enforcement tools trustees use varies by district. For example, trustees in some districts participate in order modification or garnish wages, but trustees in other districts don’t have those tools. Further, trustees have limited tools for enforcing child support payments from non-custodial parents living outside of Kansas. DCF has more enforcement tools for those interstate and international cases.

- State law only allows court trustees to administer child support cases that are not DCF’s responsibility. This means court trustees cannot serve parents who are receiving public assistance.

- This creates a unique dual track system in Kansas. If a parent is receiving public assistance, their case is automatically assigned to DCF. If a parent isn’t receiving public assistance, the entity that handles their case may be determined by where the parent lives.

- Cases may be automatically assigned to a court trustee or a parent may need to apply for their services, depending on the judicial district they live in. However, these cases may still end up with DCF for two reasons. First, parents can choose to use DCF instead of the trustee if that’s their preference. Second, trustees can choose to refer a case to DCF if trustees can’t provide the necessary services.

- Parents in the other 14 judicial districts without a trustee must apply with DCF to receive services or use a private attorney.

Overall System Issues

A small number of parents we talked to expressed frustration and a lack of communication, regardless of whether they were served through DCF or court trustees.

- We spoke with a handful of parents who participated in these services to understand their experiences. Specifically, we contacted about 300 randomly selected parents who used DCF services to participate in our interview (out of an approximately 130,000 caseload). We also reached out to 203 parents we had contact information for who used trustee services. Of those, 18 parents agreed to speak with us. 2 of those parents responded to 2 different interviews about their experiences with both CSS and Trustees. Although their responses are not projectable, they indicate potential problems.

- The parents we interviewed were both mothers and fathers, came from different judicial districts in Kansas, and were comprised of different races and ethnicities.

- Several parents (6 of 11) who used DCF services were dissatisfied with their overall experience. The other 5 parents were either satisfied (4) or neutral (1). Of the 11 parents surveyed, 6 parents expressed concerns with the overall time it took to process their case. 4 mentioned needing additional communication or information on their case. 3 parents told us that contractor staff lost their case paperwork. Below are a few examples of parents’ dissatisfaction with DCF.

- “I think [if] they are asking for [a] certain document, they need to stay on the phone with you and explain or answer questions about other information you need to fill out on there, rather than not being sure what we need. It would be easier if someone walked you through it.”

- “I called them, and they had lost all of our information and we had to start all over. It was May or June [and] I gave them the paperwork in April. Then, 90 days had gone by, and nothing had been done.”

- “I contacted DCF . . . in May . . . I called back in August; they had lost the paperwork.”

- “I have tried to get through and the wait time was long. I wait anywhere from 30-45 minutes then decide to give up.”

- Several parents (6 of 10) who used a trustee told us they needed more communication about their case. 4 of the 10 parents told us they did not know they had a trustee who oversaw their case. 1 parent we spoke to did not understand why their case was transferred from their trustee to DCF. Below are some examples of parents’ dissatisfaction with trustees.

- “I guess I would be dissatisfied [in general with my trustee] because I have never been given contact information and have never had anyone reach out if I had any questions.”

- “It was very hard to contact the trustee. [There were] lots of phone messages and emails. I would go a month or multiple weeks at least without hearing anything back after leaving multiple messages.”

- “I hadn’t heard anything from September to the end of November and I had to contact them again because nothing has changed. And now here we are mid-January, and it is still not back to the correct amount.”

- “The trustee told me I had to go to CSS [DCF], and this didn’t make sense because I thought the whole point of trustees is to help with enforcement. When I needed help with enforcement, it wasn’t available because the non-custodial parent had moved to Florida.”

- Those parents who were satisfied with or neutral towards DCF (5 of 11) and trustee services (5 of 10) reported being happy with services, hopeful about progress knowing someone was working on their case, and supportive staff. Below are a few examples of what parents told us:

- “I am hopeful that things will get better. We are working toward a common goal of helping a child out.”

- “I am more hopeful than when I was not working with them. I didn’t think I would ever have something come of the situation. Since working with them, I feel like someday or sometime, I will be getting the results I am looking for.”

- “It is stress free. I can focus my time on raising my child, and not having to go back to the courts every time a payment isn’t made.”

- “They are doing what they can to fix the situation…The situation is difficult, but they are trying.”

- Due to the small number of respondents, it’s unclear whether these issues represent a systematic problem within DCF and the trustees. However, these responses do indicate a potential issue surrounding a lack of communication from both sides of the state’s child support system.

Kansas’s dual track child support system may create unequal costs for some Kansas parents.

- Parents who use DCF services (either voluntarily or mandated) do not get charged for the services. DCF’s child support program relies solely on state and federal funding. About 70% of its funding is provided through federal funding and grants. About 30% of its funding comes from the state’s social welfare fund.

- Parents using a court trustee are subject to service fees. Unlike DCF, court trustees do not receive state or federal funding. As such, their child support services are funded through a parent-assessed fee.

- Trustee fees varied from 3% to 5% across judicial districts. As a hypothetical example, a monthly child support payment of $200 would cost parents $6 a month in the 13th judicial district (3% fee) and $10 a month in the 7th judicial district (5% fee). State law prohibits trustees from assessing more than a 5% fee.

Kansas’s dual track system prevented us from evaluating the state’s child support system as a whole.

- We were asked to evaluate the state’s child support system. As part of this work, we were asked to determine if one provider (i.e., court trustees or DCF and its contractors) is more effective than the other. We were also asked to determine if people had equal access to public child support providers in the state.

- The trustee system has no statutory requirements to collect consistent performance data. Trustees told us they follow guidance from statute, administrative orders from the district court judge, and local court rules. However, none of these items include payment timeliness or requirements to report data. Additionally, court trustees don’t need to meet federal standards because they don’t receive federal funding. As such, the state’s trustee child support system did not have any statewide performance data for us to evaluate. We did not ask individual trustees to provide us with data they may keep. We would not have been able to make useful comparisons across trustees or to DCF because of differences in systems, services, and performance expectations.

- The lack of statewide trustee data and performance requirements prevented us from assessing trustees’ effectiveness or timeliness. This also prevented us from comparing the trustees’ performance to DCF. The Office of Judicial Administration (OJA) officials told us they are in the process of updating their system to have statewide data. As a result, the remainder of the report focuses on DCF’s child support services.

Issues Related to DCF Effectiveness and Timeliness

DCF’s outdated computer system prevented us from determining how timely and effective its services are.

- DCF and its contractors use a nearly 25-year-old computer system for child support case management. The system runs on a mainframe and cannot be used to meet current business needs. It requires extensive training to use and requires manual user input for many of its functions.

- The limitations of the case management system prevented us from analyzing data to determine the timeliness and effectiveness of DCF services. We attempted to get detailed, case-level data from DCF’s system. While DCF collects this data, they were unable to extract it from their system. DCF officials told us this was due to system limitations such as limited staff being able to write and run queries on the system.

- We were also unable to review a sample of child support cases because of the time and training it would require to learn and use DCF’s case management system. DCF staff told us it would also require a substantive amount of their time to train us on the system. Lastly, we would have to review the live system, which creates a risk we could disrupt child support operations or corrupt the live data.

- DCF officials were aware of the limitations of the case management system. In 2020, DCF received an independent evaluation from Midwest Evaluation and Research, LLC (a company helping foundations, schools and governments evaluate and improve their programs). That report noted similar obstacles in obtaining detailed child support data from DCF’s system. The report recommended DCF update its computer system to address these limitations. DCF staff told us that a computer upgrade could improve their ability to query its data and make it easier to review individual case files. Staff also agreed it could improve their ability to oversee its two contractors.

- DCF is in the process of updating the outdated case management system by moving it off the mainframe and to a more modern platform. The $11.7 million project also includes more automation and less manual staff involvement. DCF began the system upgrade in 2021 with an original anticipated completion by February 2024. As of February 2023, the project was behind schedule. The most recent IT project management report placed this project in alert status. At the time of this report, DCF staff was working on additional software procurement and an updated project schedule.

- The Kansas Payment Center (KPC) processes all child support payments in the state. We reviewed data on payments processed through the KPC and did not find any issues with payments made being properly dispersed. This means if a payment is made in the state, it is getting to the parent in an allowable timeframe. Therefore, lack of collection is not due to disbursement issues.

We relied on 4 federal performance benchmarks as indicators of DCF’s child support performance.

- To get federal funding, DCF is required to meet 5 federal requirements related to child support, 4 of which directly measure establishment and enforcement. Because we could not independently evaluate DCF’s child support data or case files, we relied on their performance on these 4 federal requirements instead. These should be seen as general indicators of DCF’s performance. Specifically, we reviewed the following performance measures from fiscal years 2017 to 2021.

- Paternity Establishment: This measures the percentage of children born out-of-wedlock with established paternity compared to a prior year. Determining paternity is a critical step to secure a child support court order.

- Support Order Establishment: This measures DCF’s ability to move a case from the establishment phase to the enforcement phase. To do this, DCF must successfully obtain a child support order from the court.

- Collection Enforcement: This measures the total amount of child support collected on DCF cases compared to the total amount owed.

- Debt Enforcement: This measures the number of delinquent cases actively paying towards a debt.

- Each of these federal requirements has a minimum and maximum threshold for states to meet. These thresholds vary between establishment and enforcement services. States must meet the minimum threshold to avoid financial penalties. Conversely, states performing near or above the maximum threshold may receive additional funding incentives. A state’s performance on these requirements provides a general indicator of how well its child support system is working.

- The data DCF uses for federal reporting is different than the detailed data we attempted to review. We reviewed the data DCF submits to the federal government and found no significant errors or inconsistencies. This data is also subject to federal data reliability reviews. Although we determined the data to be generally reliable, these metrics are not based on detailed case-level data. These metrics measure high-level child support case information, largely based on aggregated data. Historically, DCF has been able to use certain queries to obtain this level of information from its computer system.

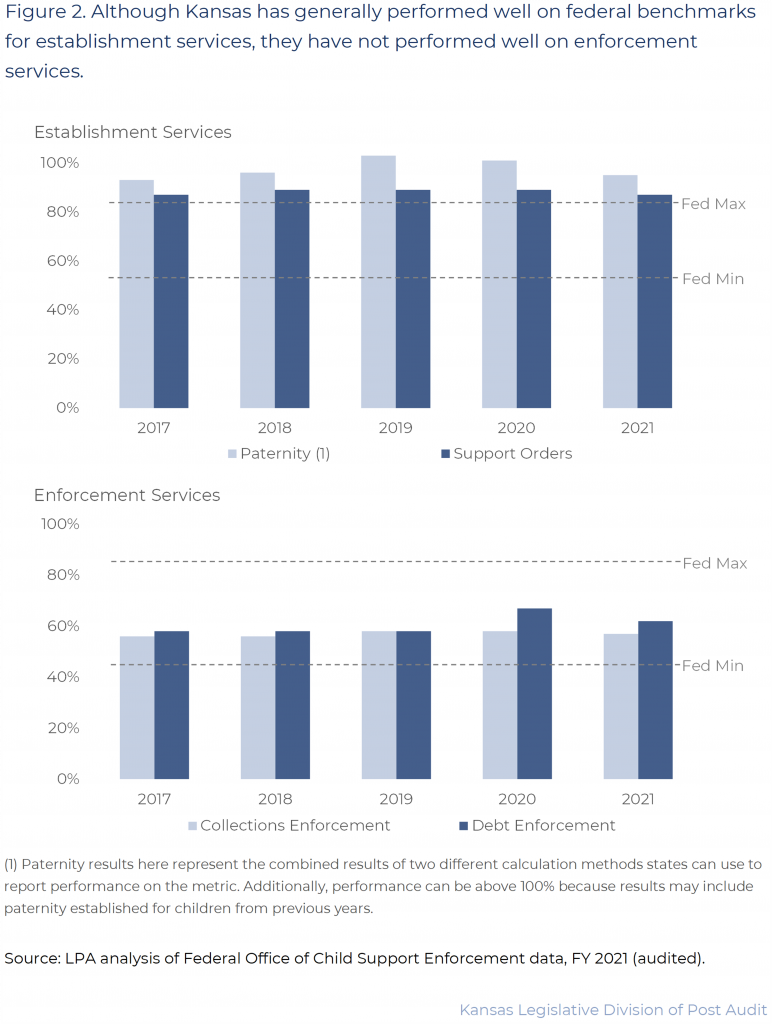

In recent years, DCF performed well on federal requirements to establish child support cases, but not on requirements to enforce those cases.

- We reviewed federal child support performance reports from fiscal years 2017 through 2021. During this time, DCF consistently performed well on establishment requirements and worse on enforcement requirements, as Figure 2 shows.

- As the top portion of the figure shows, DCF consistently exceeded the maximum performance threshold for establishing paternity and support orders. DCF’s performance on these two requirements was relatively consistent over the 5 years we evaluated.

- As the bottom portion of the figure shows, DCF’s performance was above the minimum requirements for enforcing payments, but well below the upper threshold. DCF’s performance on these two requirements was relatively consistent over the 5 years we evaluated.

- Although DCF met the minimum requirements for enforcing payments, DCF’s performance still resulted in a significant number of unmade payments. For example, in fiscal year 2021, DCF only collected 57% of child support payments that were owed. We estimated that of the roughly $584 million in total payments owed that year, only about $333 million was collected.

DCF officials told us the difficult nature of their cases and certain administrative hurdles make it difficult to enforce child support payments.

- The nature of DCF’s child support cases can make them difficult for DCF and its contractors to enforce. Many of DCF’s cases involve low-income families. Some parents also actively try to avoid paying court-ordered child support. DCF officials told us both things make collecting child support payments difficult for contractors. For example, low-income parents are more likely to experience financial hardship preventing them from making payments. Also, parents who actively avoid payments may not be easy to track down.

- Cases being transferred from a trustee are often more difficult to enforce payments. DCF officials told us that when trustees’ cases come to them (either because the trustee or the parent initiates the transfer) the cases generally are already delinquent. This makes it even more unlikely for DCF’s contractors to successfully enforce payment on these cases.

- Most of DCF’s and its contractor’s actions require court approval, which can slow their collection efforts. DCF and contractors have several enforcement tools to help them collect delinquent payments. For example, DCF can garnish income from checking or savings accounts, but this requires court approval. DCF officials told us this extra judicial step, while necessary, also slows down the collection process.

Issues Related to DCF’s Child Support System and Processes

DCF and its contractors don’t have the tools to quickly identify and address delinquent payments.

- Once a child support case has been established with the court system, and the non-custodial parent’s employment information is known, DCF contractors file an income withholding order. The withholding order automatically deducts child support payments from the parent’s paycheck. Payments are automatically made so long as the employment information remains current, and the employer cooperates. A payment is considered delinquent if it doesn’t come through on time. This can happen when a parent loses employment, has a reduction in work hours, or doesn’t keep their employment information current.

- There are a few reasons why it is important to quickly identify delinquent payments. First, addressing the problem quickly ensures custodial parents don’t experience undue financial hardship from late payments. Second, the more time that passes, the more difficult it could be for staff to identify the non-paying parent’s location, current employer, or additional assets that could be used as payment.

- Neither DCF nor its contractors had a process to quickly identify delinquent payments. The state’s case management system is old and limited in its capabilities. We spoke to officials from both of DCF’s contractors. Those officials told us they can view individual cases in the system but cannot use it to flag delinquent cases automatically (outside of system-wide reports they run). Instead, DCF officials told us they and the contractors largely rely on parents to call and notify them of any late payments. DCF does have various system reports and alerts, but they are not immediate notifications.

- DCF is updating its case management system, but that project is experiencing significant delays. DCF officials told us they think the computer system, once updated, should help automate parts of the case review process, especially in terms of flagging late payments.

DCF’s use of federal performance measures to monitor contractors’ performance is too simplistic to identify poor performance.

- DCF’s current child support contracts require that contractors meet certain performance measures. Those performance measures are largely based on the same 5 federal metrics discussed above. When privatizing a state function, it’s important to establish strong performance metrics to monitor contractors’ performance. As discussed above, the contractors consistently met those federal metrics. However, relying on those metrics may limit DCF’s ability to monitor its contractors’ performance.

- Additional metrics with specific performance expectations could help identify performance issues and increase child support payments. The 2020 Midwest Evaluation report had similar findings. It also found that relying on the federal measures limited DCF’s ability to monitor its contractors’ performance.

- DCF officials told us they also require contractors to meet other outcomes related to things like maintaining confidentiality, customer service, number of income withholdings filed, etc. DCF officials told us they have a compliance unit that helps review these and other performance metrics. Although these are important things to monitor, they do not directly monitor timeliness or payment accuracy.

- DCF officials told us they were working on developing additional and more specific performance metrics for its contractors. Updating the system would help DCF evaluate things like the length of time to modify a court order, identification of cases by payment timeliness, and the geographic trends across the state. However, DCF’s system upgrade was behind schedule at the time of the report and DCF was working on an updated project schedule.

Kansas’s low national rankings in child support enforcement may be due to the state’s unique system and outdated technology.

Kansas’s child support services through DCF and its contractors performed worse on federal enforcement benchmarks than most other states.

- We compared Kansas’s performance on the 4 federal child support requirements to all 49 other states in fiscal years 2017 through 2021. Results were consistent across all 5 years, so we only discuss the most recent year, 2021, below.

- Kansas performed near the middle compared to other states on the 2 establishment requirements. For example, Kansas established paternity in 95% of cases compared to a high of 165% in Arizona and a low of 81% in New York as shown in Figure 3 in the online version of this report. Kansas consistently ranked near the middle of all other states in all 5 years we reviewed.

- Kansas ranked near the bottom nationally on the 2 enforcement requirements. For example, Figure 3 shows all states’ performance on collections enforced. As the figure shows, Kansas collected 57% of payments compared to a high of 84% in Pennsylvania and a low of 51% in Louisiana. Kansas consistently ranked near the bottom in all 5 years we reviewed. Kansas did see an increase in collections during 2020 due to COVID-19 assistance that DCF could intercept for child support collections. However, it did not have a significant impact on performance and levels have since returned to pre-COVID collection amounts.

Kansas’s trustee option appears to be unique compared to other states, which may skew its national performance metrics.

- Kansas has a dual track child support system in parts of the state, where child support cases may be administered by DCF or by court trustees.

- DCF officials confirmed that to their knowledge, Kansas was unique. We also spoke to officials in Colorado, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, and Oregon to understand how their child support systems compared to Kansas. We chose these states because they included a variety of approaches to child support management. We also selected these states because they represented various performance levels compared to Kansas. Those states did not report they have a trustee option for child support cases.

- It’s possible Kansas’s unique dual track system negatively skews its performance compared to other states. That’s because the data does not include any of the cases trustees handle because they are not required to report on federal performance requirements. Typically, trustees handle cases that require less enforcement intervention. Conversely, DCF tends to handle more complex cases that require more significant enforcement. As a result, Kansas’s performance reflects some of the state’s more challenging cases to enforce. This is unlike any other state.

Kansas’s DCF child support services did not have key computer system features and collection tools that some other states had.

- We spoke to child support officials in the same 5 other states to understand their enforcement processes. We also reviewed national reports on state child support systems.

- Several states’ computer systems are capable of automatically flagging delinquent payments. Officials in Colorado, Nebraska, and Oregon told us their systems produce automatic alerts when cases are delinquent and need attention. Montana officials told us their system has some, but not fully automated capabilities. DCF and its contractors cannot automatically flag late payments. This means DCF mostly relies on parents and delayed system reports to notify them of late payments. In turn, this delays possible enforcement actions and payments, especially when parents are less vocal about problems with their cases.

- Colorado, Oklahoma, and Texas use a mandatory insurance payment intercept program. In these states, when a non-paying parent files an insurance claim, agency officials are automatically notified. States can then intercept any insurance payment made to the parent to use towards child support. Kansas does not have a mandatory reporting requirement for insurance companies. That means insurance companies may not submit information on insurance claims. DCF officials also told us, when insurance companies do report a claim, it requires a very manual process to intercept the payment. Even with an updated case management system, this tool may still be limited in Kansas because insurance companies are not required to report this information.

- Officials from Oregon and Nebraska told us they can also (automatically) administratively suspend parents’ drivers’ licenses for failure to pay. DCF officials told us they can work with the Department of Revenue to restrict drivers’ licenses, but it may require a prior contempt charge and is not applied to all cases. An updated case management system may help with this tool, but court approval is still required in some instances with this tool. DCF is working with federal partners to maximize what they can administratively do with garnishments.

Conclusion

We did not draw any conclusions beyond the findings already presented in the audit.

Recommendations

- The Legislature should consider requesting DCF officials to periodically report on the status of its case management system upgrade to relevant legislative committees.

Agency Response

On April 4, 2023, we provided the draft audit report to DCF and the Office of Judicial Administration. Only DCF chose to submit a response. Their response is below. DCF officials disagreed with a few of our findings regarding the status of their ongoing IT modernization project, automated capabilities, and their oversight of their contractors. We reviewed the information agency officials provided and made minor changes to parts of the report to clarify our conclusions. However, we did not substantially change our findings.

Department for Children and Families Response

Thank you for the opportunity to provide a response to the Performance Audit Report: Evaluating Whether Services to Collect Child Support Payments in Kansas are Effective and Timely (April, 2023). We appreciated the professional conduct of the LPA staff during the course of the review. The Kansas Department for Children and Families (DCF) respectfully submits the following responses for the audit findings listed below.

- Kansas court trustees also can provide child support services, but they generally only provide enforcement services.

The report indicates that the presence of the court trustee system in Kansas creates a sort of “dual track system”. From a DCF perspective, the impact is even larger. The availability of trustees in over half the counties does not create just a “dual track system”, but rather a multi-track system, unlike any other state in the nation. In all other states, parties have only two options – the IV-D program or private counsel/self-representation. In Kansas, DCF shares cases not only with private counsel, but also with the Trustees. This creates a layer that does not exist anywhere else.

Overall System Issues. The LPA report indicates that the small sampling of case participants “indicate a potential issue surrounding a lack of communication from both sides of the state’s child support system.” DCF would suggest that the represented sample of customers is far too small to be projectable or arguably to draw any conclusions about a systemic issue with communication. While there are always going to be issues of human error in any organization, it is not something DCF believes is unique in Kansas. The actions DCF is regularly taking were not explained in the LPA report, leaving the reader with the impression that nothing is being done to address communication gaps.

The dissatisfaction of customers noted in the LPA report is something DCF addresses continuously with its contractors. There are bi-weekly meetings regarding the Interactive Voice Response System (IVR) and Customer Contact Centers; clear expectations for performance and monthly reporting requirements. In addition, quality assurance reviews are conducted within CSS Administration as well as by the contractors themselves. Further, DCF Kansas was one of ten core states that voluntarily participated in a nationwide child support survey in 2022 to garner opinions from not only the IV-D customers, but all others as well. One goal we had this year was to learn more about what is causing confusion for customers in the child support program and how we can better assist to streamline processes or help people navigate the very complex system. The final report is not yet available; however, these points were relayed to LPA during the interviews.

- DCF’s outdated computer system prevented us from determining how timely and effective its services are.

The report indicates that 0% of the tasks for the Replatforming efforts have been completed. The statement that 0% of the tasks for the Replatforming are done is inaccurate. The first Phase of the Replatforming as a whole is not complete; however, there has been extensive work toward completion. These include:

- All contracts and software have been procured;

- project organization and staffing is complete;

- communication protocol is complete;

- project documentation site has been created and kept current;

- project dashboards are in place; data has been de-identified; and

- data migration to the testing environment is 95% complete just to name a few tasks.

The project overall does have some risk due to unforeseen circumstances with the data migration and project staff losses; however, it has stayed on scope, and within budget. Architecture and Design/Development teams are on track. Interfaces and Security teams are also on target. Currently, the anticipated rollout for phase one is still 2024.

- Issues Related to DCF’s Child Support System and Processes

The Report states that DCF and its contractors don’t have the tools to quickly identify and address delinquent payments indicating that, “Neither DCF nor its contractors had a process to quickly identify delinquent payments.”

DCF respectfully disagrees with this conclusion. While the system does not support an immediate notification such as more modern systems may, there are alerts that are generated daily indicating many things regarding non- payment or the end of employment. For example – any time an obligor obtains new employment that is reported, and an alert is generated for the workers to issue income withholding. Alerts are also generated notifying workers when employment ends so that they may initiate locate or research for new employment. We receive alerts from the federal quarterly wage report as well as Kansas New Hire to identify employment for obligors. In addition to the alerts, workers are provided a non-paying report that is generated monthly. Both contractors utilize this report in their own internal case management software to be worked daily by case workers. While parents are a great resource in alerting DCF and contractors to nonpayment or new employment, they are far from the most reliable or utilized method.

The auditors also concluded that DCF’s use of federal performance measures to monitor contractors’ performance is too simplistic to identify poor performance–stating, “DCF’s current child support contracts only require that contractors meet 5 federal performance metrics.”

DCF respectfully disagrees with this finding. The current contracts have a multitude of requirements, with potential liquidated damages for noncompliance. The contracts state: “Effectiveness will be measure by outcomes that are within the contractor’s control such as meeting all federal and state timeframes; sending and processing customer service paperwork timely and accurately; calculating financial credits and debits accurately and timely; maintaining program and system confidentiality and security; and, addressing customer issues timely, professionally, realistically, and while applying IV-D policy and procedure correctly.” Within the contract, there are specific requirements regarding training, casework, etc. The federal measures referenced in the LPA report are not actually specific measurements for which the contractors must meet. The requirement was that they improve baseline numbers. (Kansas RFP EVT0007816, p. 75). This is but one criterion used to measure contractor performance.

DCF has a dedicated Contract Compliance unit that reviews monthly reports submitted by both contractors that include: Case Management, Legal Management, Finance Management, IVR Management and Contact Center Management. DCF conducts internal reviews of samplings of cases in each area, as well as reviews of reports submitted, and makes recommendations monthly based on findings. Any deficiencies have been addressed immediately through meetings with contractors and/or documented findings. In addition to the DCF controls, both contractors are required to have internal Quality Assurance units that conduct regular reviews of random samplings of case work. Those findings are required to be submitted monthly to DCF. While it is true, this unit is a work in progress, DCF monitors far more than federal performance measures and does hold contractors accountable.

Conclusion

We thank the Legislative Post Audit team for the opportunity to discuss the child support program. It is a very complex area with many nuances when comparing programs to programs; and there are vast differences between state programs depending on population, budget, updated systems, etc. Thank you for the opportunity to provide clarification and response.

Sincerely,

Laura Howard, Secretary

Patrick M. Roche

Patrick Roche, Audit Services Director

Appendix A – Cited References

- Midwest Evaluation (2020). Final Report: Evaluation of the Managerial Accountability and Consonance of the Kansas IV-D Program.

- Office of the Washington State Auditor (2020). Child Support Payments: Increasing past-due collections through mandatory interception of insurance payments.