Juvenile Justice Reforms: Evaluating the Effects of Senate Bill 367

Introduction

Representative John Barker requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its April 30, 2019 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- Has Kansas increased community-based services for juveniles since the passage of Senate Bill 367?

- Do juvenile court judges and other stakeholders think Senate Bill 367 reforms on the juvenile justice system have been effective?

- Does Kansas have a process to determine if the reforms included in Senate Bill 367 were successful or not?

Our review of Senate Bill 367 reforms (the reforms) covered juvenile offender placements for fiscal years 2015 to 2019 and community program funding for fiscal years 2017 to 2019.

We reviewed Kansas Department of Corrections (KDOC) and the Office of Judicial Administration’s (OJA) juvenile offender data to understand the reforms’ effects on out-of-home juvenile placements. We also reviewed KDOC expenditure data to identify savings from the reforms. In addition, we evaluated how much of those savings KDOC invested in new community programs for juvenile offenders.

We surveyed 1,759 stakeholders to collect their opinions on the success of the reforms including judges, sheriffs, defense attorneys, prosecutors, probation officers, and members of regional Juvenile Corrections Advisory Boards. We reported only on the responses we received. The results cannot be projected.

We reviewed state law and interviewed KDOC and OJA officials to understand Kansas’ process to monitor the reforms’ effectiveness. We compared Kansas’ process to those in three other states (Kentucky, Nebraska, and South Dakota). We choose those states because they all had recent juvenile justice reforms like those in Kansas.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

However, our ability to fully answer the first audit question was limited by a lack of juvenile offender data. These data issues limited our ability to conclude on how the use of in-home probation and Immediate Intervention Programs have changed since the reforms.

Audit standards require us to report on any potential impairments to our independence. We reviewed the work of the Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee as part of this audit. Although not a legislative committee, members of the legislature serve on this committee (in addition to other stakeholders). However, our work related to this committee was limited and we do not think our independence was impaired.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. In this audit, we found issues with KDOC’s process to ensure judicial districts use grant funding appropriately. That finding is discussed in more detail later in the report.

Senate Bill 367 reforms reduced out-of-home placements and increased community program funding for juvenile offenders in Kansas.

Senate Bill 367 Reforms

Senate Bill 367 aimed to reduce the number of juvenile offenders put in out-of-home settings like prisons, jails, and group homes.

- National research suggests that limiting juvenile offenders’ time in out-of-home placements lowers their risk to reoffend. This includes limiting their time in juvenile facilities like prison, detention centers, and group homes.

- Senate Bill 367’s reforms (the reforms) passed during the 2016 legislative session. The reforms sought to limit juveniles’ time in out-of-home placements and the juvenile justice system. They did this in three main ways:

- The reforms aimed to reduce the number of juveniles entering the justice system. It did this through the Immediate Intervention Program. This program existed as an option before the reforms. The reforms made it mandatory that the program be offered to juveniles for a first misdemeanor offense. Some crimes are excluded from this requirement (e.g., sex offenses). Intervention programs are similar to diversion in that they do not result in a conviction. However, individuals on an intervention program do not have to waive certain constitutional rights like they do for a diversion.

- The reforms reduced out-of-home placement options. Before the reforms, juvenile offenders could be sentenced to in-home probation or an out-of-home placement. Juvenile offenders on probation live at home but are monitored by community probation officers. Out-of-home placements are in facilities, such as group homes or a juvenile correctional facility. The reforms practically eliminated group homes as a placement option. It also restricted placement in a juvenile correctional facility to just the highest risk and most serious offenders.

- The reforms put new limits on how long juvenile offenders remain in the justice system. Before the reforms, there were no limits on how long juvenile offenders could be on probation. There were also no limits for how long they could be held in detention (i.e., temporary jail placement) or their total case length. The reforms created hard limits in all three of these areas. For example, with some exception the reforms limited juvenile offenders’ probation time to no more than 6 to 12 months depending on the crime and risk level.

The reforms also sought to create new community programs aimed at reducing recidivism.

- Stakeholders anticipated the reforms would create savings for the state. That is because the reforms intended to keep more juvenile offenders at home. This would result in fewer occupied beds at juvenile facilities, which would lower the Kansas Department of Correction’s (KDOC) costs and create state savings.

- The reforms allowed KDOC to invest any savings to create or expand community programs. These programs serve juveniles who are at home but on probation.

- The programs must be evidence based and seek to reduce recidivism. Examples of these programs include family therapy, anger management, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

Juvenile Offender Placement

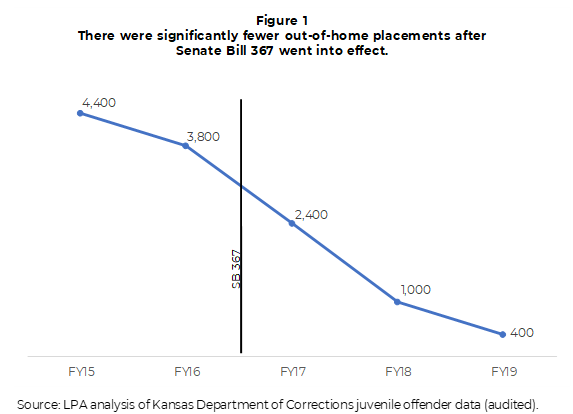

Out-of-home placements declined by 40% to 60% each year since the reforms were made.

- Out-of-home placements were declining even before the reforms were made. Figure 1 shows the change in out-of-home placements since the reforms went into effect. As the figure shows, out-of-home placements dropped from 4,400 to 3,800 between fiscal years 2015 and 2016. This was a 14% decline.

- Out-of-home placements dropped significantly after the reforms went into effect in 2017. As Figure 1 also shows, out-of-home placements declined by about 40% to 60% each year after the reforms went into effect. In fiscal year 2019 there were only about 400 out-of-home juvenile placements, including placement in the state’s juvenile correctional facility.

We lacked data to review the reforms’ effects on in-home probation or Immediate Intervention Programs.

- KDOC and the Office of Judicial Administration (OJA) are both responsible for overseeing the state’s juvenile offenders. Both agencies are responsible for supervising juvenile offenders on in-home probation.

- KDOC is also responsible for all juvenile offenders in an out-of-home placement. We expected each agency to have a complete dataset of juvenile offenders under their supervision or custody.

- KDOC did not have a complete dataset of juvenile offenders on Immediate Intervention Programs. We could not evaluate the reforms’ effects on these programs because historic data was not available. KDOC officials only began collecting this data in fiscal year 2018. Additionally, KDOC only had Immediate Intervention Program data for 79 of the 105 counites. KDOC officials told us they were still working to get reports from all counties but could not compel counties to submit data. It is also possible some counties did not have any intervention program cases or refused to implement the program, but it is not clear from KDOC’s data.

- OJA could not readily identify all individual juvenile offenders under their supervision. Although juvenile offenders are monitored and tracked in the judicial districts they live, OJA had not compiled that information into a centralized, statewide dataset. As a result, we could not evaluate the reforms’ overall effect on in-home probation placements statewide. OJA officials told us they were in the process of implementing a centralized data system to collect this information.

- As of fiscal year 2019, judicial districts reported about 1,400 new juvenile offenders under OJA supervision.

Community Programs for Juvenile Offenders

The Kansas Department of Corrections must use savings from the reforms to fund new or expand existing community programs.

- The evidence-based programs fund (the fund) was created to collect savings from the reforms. Since fiscal year 2017, the fund collected about $40 million. Most of the $40 million comes from fewer occupied beds at juvenile facilities. Every year KDOC determines how much it saved from the reduced bed use and transfers that amount from its budget into the fund.

- The reforms required KDOC to use the fund to expand or create new community programs for juveniles on in-home probation. KDOC can use the funds on new statewide contracts or on local grants to create or expand programs in the state’s 31 judicial districts.

- In both cases, the programs must be evidence based and aim to reduce juvenile offender recidivism. Examples include family therapy, anger management, education, and drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs. Contracted community service providers or probation officers delivered the programs to juveniles.

The Kansas Department of Corrections has spent about $9 million to create or expand community programs for juvenile offenders since the reforms.

- Since fiscal year 2017, KDOC spent about $9 million from the fund on new state contracts and local grants to create new community programs. This represents new, increased funding for community programs because of the reforms. KDOC used the funding on new statewide services like sex-offender treatment and family therapy.

- KDOC also funded judicial district grant requests to expand or create local programs. Since fiscal year 2018, 30 of the state’s 31 judicial districts received a grant from the fund. The one district that did not receive a grant told us they were not ready to apply. The unused $31 million remained in the fund for future use.

- Beginning in fiscal year 2021, KDOC plans to invest about $22 million a year on new community programs and services for juvenile offenders. KDOC officials budgeted this spending over a 10-year period. KDOC plans to invest these funds on new substance abuse programs, counseling services for families, and other programs to serve juvenile offenders in the community.

Community programs were generally available across the state, but more programs may still be needed.

- KDOC tracked whether 10 important program types were available across the state’s 31 judicial districts:

- Anger Management

- Cognitive Behavior

- Drug and Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Education

- Family Therapy

- Independent Living

- Mental Health Services

- Mentoring Services

- Sex Offender Treatment

- Vocation

- In fiscal year 2018, 29 judicial districts (94%) offered at least 7 of the 10 community programs. Only two districts (6%) offered six or fewer of the program types. KDOC officials told us the 10 program types represented a thorough approach to juvenile treatment. However, districts are not required to offer all 10 program types.

- A little more than half (61%) of the Juvenile Corrections Advisory Board members we surveyed said there were adequate community programs in their districts. Juvenile Corrections Advisory Board members help oversee and advise on community programing for juvenile offenders. Of the 314 members surveyed, 98 members (31%) responded, representing 29 of the state’s 31 judicial districts. Of those that responded:

- 61% said there were adequate programs in their district to serve juvenile offenders. This included members from 26 of 29 responding districts.

- 30% said there were not adequate programs. This included members from 20 of 29 responding districts. Most of these districts also had at least one member that said programming was adequate above.

- 9% said they did not know.

- A lack of qualified staff was the most common reason given for not having adequate programing.

- Judicial districts can apply to KDOC for grants to address their program needs. Our review of the grant process showed that KDOC approved nearly all grant applications since 2017. However, a lack of qualified staff in some parts of the state may not be solved through additional funding.

Other Findings

The Kansas Department of Corrections did not have a process to ensure judicial districts used grant funds on appropriate programs.

- We reviewed KDOC’s internal controls to ensure judicial districts appropriately used grant funding for community programs. We did not independently verify how judicial districts used their funds.

- Judicial districts apply for grant funding from KDOC to support their local program needs. For example, in fiscal year 2019 alone KDOC issued about $3.7 million in grants to judicial districts. Judicial districts kept the grant funds in local accounts. District officials were responsible for spending those funds on KDOC approved programs. Although not required by law, we expected KDOC to have a process to ensure judicial districts spent those funds appropriately.

- KDOC described a process to reconcile each district’s grant fund balance quarterly. Districts report fund balances and provide expenditure reports to KDOC. KDOC reconciles districts’ self-reported fund balance amounts to the supporting expenditure reports. This process helps track the amounts district spend. However, it does not ensure districts spend their funds appropriately (i.e., on the programs and resources KDOC approved). As a result, there is a risk judicial districts used grant funds on programs, resources, or other items not allowed by KDOC.

- We also found errors or missing documentation to complete this check in three of the five districts we reviewed. Our review was based on a judgmental sample and cannot be projected to all districts.

Some county and district attorneys did not follow the state’s new requirements on mandatory Immediate Intervention Programs because of legal concerns.

- The Immediate Intervention Program existed as an option before the reforms’ implementation. However, the reforms made it mandatory that the program be offered to juveniles for a first misdemeanor offense. Some crimes are excluded from this requirement (e.g. sex offenses).

- Some county and district attorneys were not following the new Immediate Intervention Program requirements. We spoke with officials at 10 county attorney or judicial district offices. We spoke to these 10 because we heard they may not have been following the new program requirements.

- Six counties were not offering Immediate Intervention to any juveniles, contrary to the statutory requirement. In most cases, officials told us the county is only offering a traditional diversion program. At least two additional counties were offering Immediate Intervention but only for certain cases. This means in some parts of Kansas a juvenile may not be offered the opportunity to avoid prosecution as required by law.

- Some prosecuting attorneys had concerns with parts of the new mandatory Immediate Intervention Program requirements. Officials told us it was unconstitutional to remove their discretion to determine which cases to prosecute. They cited separation of powers as the basis for their argument. At the time of our work, the Kansas Judicial Council was working with prosecutors and other stakeholders on suggestions to amend the statute and address this concern.

It is possible the reforms impacted the state’s foster care system, but the Department for Children and Families was still compiling data on this issue during our audit.

- Childcare advocates and the stakeholders we surveyed said more juvenile offenders have entered foster care due to the reforms. Legislative concerns about this issue led to two Department for Children and Families (DCF) budget provisos to study the issue further. Additionally, KDOC officials told us there is ongoing study between multiple state agencies to address the reform’s impact on this population.

- A fiscal year 2019 budget proviso required DCF study the needs of youth involved in both the state’s foster care and juvenile justice systems (sometimes referred to as crossover youth). DCF released its findings in a June 2019 report. Among other things, the report cited a need for short-term placements, more mental health services, and more family support.

- A fiscal year 2020 budget proviso required DCF study the reforms’ effects on foster care placement and the juvenile justice system. DCF is working to compile and analyze data on this issue and plans to report its findings in January 2020.

Stakeholders told us several Senate Bill 367 reforms had a negative impact on the juvenile justice system.

We asked stakeholders whether they thought eight key reforms had a positive or negative effect on the juvenile system.

- We surveyed stakeholders about whether they thought Senate Bill 367’s reforms (the reforms) had a positive or negative effect on the juvenile justice system.

- We surveyed 1,759 stakeholders, including judges, sheriffs, defense attorneys, prosecutors, probation officers, and members of regional Juvenile Corrections Advisory Boards. Of those surveyed, 404 responded (about 23%). We only surveyed stakeholders directly involved in implementing the reforms. As such, we did not survey juvenile offenders or their families. We did not rely on a sample for our survey. Instead, we attempted to survey all stakeholders licensed or employed with the state, counties, or judicial offices from the groups listed above. We reported only on the responses we received. The results cannon be projected.

- The eight key reforms we asked about were:

- Probation limits

- Detention limits

- Cases length limits

- Graduated responses for probation violations

- Youth level of service assessment tool

- Detention risk assessment tool

- Mandatory Immediate Intervention Programs

- Multidisciplinary teams for Immediate Intervention Programs

- Stakeholders were not required to provide an opinion on each reform. For this reason, stakeholders’ responses on the eight reforms did not add to 100%. We could not draw conclusions from stakeholders that choose not to provide an opinion on a given reform.

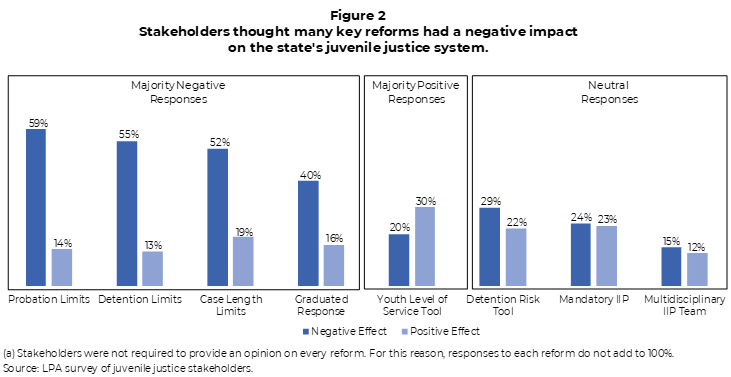

More than 50% of those who responded said the new probation, detention, and case time limits had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system.

- The reforms created new limits on how long most juvenile offenders can be put on probation, held in detention, or sentenced to prison. Prior to the reforms, judges had much more discretion over how long to sentence juveniles and under what conditions.

- Figure 2 summarizes overall stakeholders’ responses on the eight key reforms. As the figure shows, between 52% and 59% of all respondents said the three new time limits had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. For example, 59% of respondents thought probation limits had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. Conversely, 14% thought it had a positive effect. The remaining 27% did not select probation limits as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

- Some stakeholders said the new limits made it difficult to hold juvenile offenders accountable.

- “I filed less cases because there is no accountability or repercussion due to case/probation/detention limits.”

- “Lack of accountability for juvenile offenders. They have quickly learned that the Court system can do very little to them, in a short window of time (probation and case length limits).”

- Defense attorney respondents had a more positive opinion of the three limits than other stakeholders. For example, between 35% and 44% of defense attorneys thought the three limits had a positive effect. By contrast, no prosecutors thought they had a positive effect.

About 40% of respondents said the new graduated responses to probation violations had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system.

- Under the reforms, probation officers must follow a list of graduated responses if juvenile offenders violate the terms of their probation (e.g. staying out past curfew). Those responses are based on the risk level of the offender and the severity of the violation. Examples of these responses include verbal warnings, adjusted curfew, or community service work. The reforms also made it so courts can only consider detaining juveniles who have at least three violations. Before the reforms, probation officers and the court had more discretion over when and how to discipline juvenile offenders.

- As Figure 2 shows, 40% of respondents thought the new graduated response process had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. Only 16% said it had a positive effect. The remaining 44% did not select this reform as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

- Some stakeholders said the new graduated responses limited their disciplinary discretion. They also said the new responses were ineffective.

- “I have seen kids who continue to violate once they realize there are very few impactful consequences for their violations and that the sanctions are not impactful to them. So they continue to reoffend.”

- “Most profound negative impact is inability to impose detention sanctions for technical violations absent findings juveniles pose danger to others or others’ property.”

- “For some cases, juveniles have little incentive to change their behaviors as they know that detention is not a penalty for probation violations.”

- Defense attorney respondents had a more positive opinion of the graduated responses than other stakeholders. For example, about 38% of defense attorneys thought the responses had a positive effect. By contrast, only 2% of prosecutors thought it had a positive effect.

A new youth level of service assessment tool was the only reform that had more positive responses than negative.

- The reforms required KDOC and OJA to adopt a single, uniform risk and needs assessment tool to be used in all judicial districts. The agencies implemented a youth level of service assessment tool for this purpose. The tool assesses a juvenile offender’s risk to reoffend and helps determine the types of programs and supervision they need while on probation. The intent was to ensure juvenile offenders were receiving the right type of services while on probation.

- As Figure 2 shows, 30% of respondents thought the youth level of service tool had a positive effect on the juvenile justice system. 20% thought it had a negative effect. The remaining 50% did not select this reform as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

Respondents were generally split on how the other reforms impacted the juvenile justice system.

- The reforms required KDOC and OJA to create a new detention risk assessment tool. The tool is used to determine a juvenile’s risk to fail to appear for court and risk to public safety. High-risk juveniles can be held in detention while lower-risk juveniles can be released home. As Figure 2 shows, 29% of respondents thought the detention risk assessment tool had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. This was compared to 22% that thought it had a positive effect. The remaining 49% of respondents did not select this requirement as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

- Before the reforms, district and county attorneys had discretion to offer Immediate Intervention Programs. The law now requires any juvenile with a first-time misdemeanor offense (excluding sex offenses) to be offered the program. As Figure 2 shows, 24% of respondents thought the new mandatory program requirement had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. 23% thought it had a positive effect. The remaining 53% of respondents did not select this requirement as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

- The reforms also created a new multidisciplinary team that meets as part of the Immediate Intervention Program process. The team can be made up of a juvenile’s family, probation officer, and other stakeholders. The team meets to address program violations. As Figure 2 shows, 15% of respondents said the multidisciplinary team had a negative effect on the juvenile justice system. 12% said it had a positive effect. The remaining 73% of respondents did not select this requirement as having a positive or negative effect on the system.

Kansas created a process to determine if Senate Bill 367 reforms were successful, but the process has not been used.

State law created a Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee and required it to monitor the success of Senate Bill 367’s reforms.

- State law (KSA 75-52,161) established the Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee (the committee) in 2016.

- The committee’s main purpose is to guide and evaluate the implementation of Senate Bill 367’s reforms.

- The committee includes 21 members, including members of the Kansas House and Senate, judges, a defense attorney, a prosecuting attorney, a juvenile crime victim advocate, KDOC officials, OJA officials, and several others.

- State law also created monitoring requirements for the committee and other state agencies. We identified about 20 requirements related to implementing, monitoring, or reporting on the reforms.

- As designed, Kansas’ process is like those in three other states that recently made juvenile justice reforms: Kentucky, Nebraska, and South Dakota.

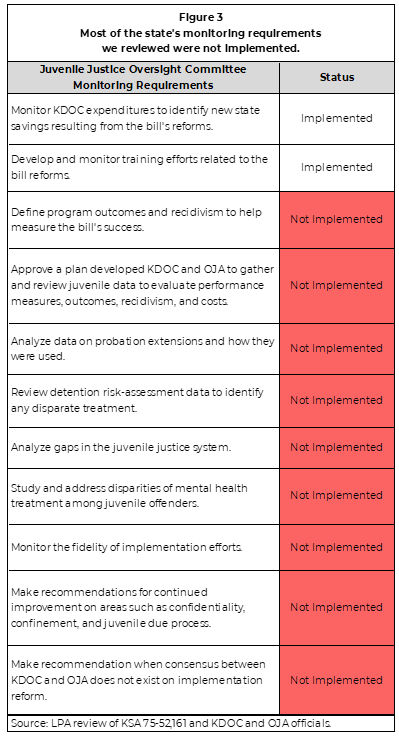

Kansas has not yet implemented most of its monitoring requirements.

- We selected 11 of the 20 requirements to review further. We selected these 11 because they were both measurable and directly related to monitoring the effectiveness of the state’s new reforms.

- We interviewed KDOC and OJA officials who served on the committee to determine if they had implemented the requirements. We also reviewed the committee’s 2017 and 2018 annual reports. As Figure 3 shows, only 2 of the 11 requirements have been implemented.

- The committee could not fully monitor the reforms’ progress because of incomplete data on juvenile offenders. KDOC and OJA are both responsible for overseeing parts of the state’s juvenile offender population. The two agencies do not have complete information on the juveniles they oversee. Further, the two agencies have not agreed on how to share data to compile a single, statewide dataset of all the state’s juvenile offenders. Without comprehensive data the committee cannot monitor the reforms’ effect on important outcomes like recidivism.

- State law did not specify a timeline for the monitoring requirements. The reforms represented a large and complicated transformation of the state’s juvenile justice system. KDOC and OJA officials told us the committee’s focus in the first few years was on implementing the reforms. They told us the committee should be able focus more on monitoring the effectiveness of the reforms in the future.

Conclusion

Kansas’ recent reforms for its juvenile offenders are extensive and still relatively new. They appear to be keeping juvenile offenders out of institutions like jails and prisons. However, many stakeholders familiar with the new reform processes had negative views of how the reforms have affected the state’s juvenile justice system. We could not tell if the negative opinions reflect stakeholders desire to maintain the status quo or whether they reflect actual shortcomings of the reforms. That is partly because the state lacked adequate data and has not yet completed many of the monitoring efforts included in state law.

Recommendations

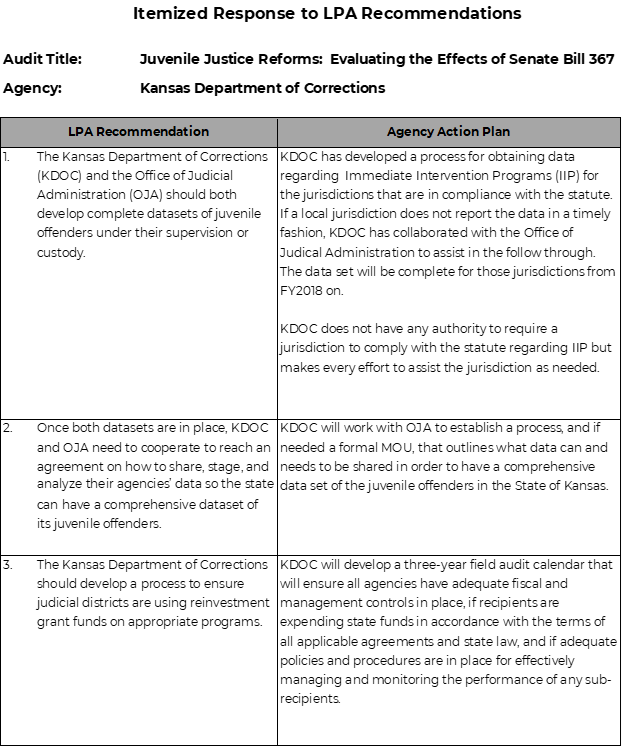

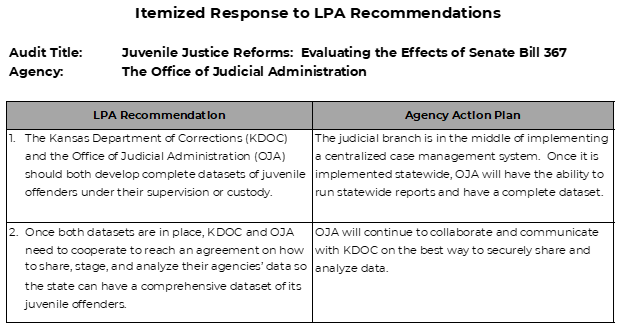

- The Kansas Department of Corrections (KDOC) and the Office of Judicial Administration (OJA) should both develop complete datasets of juvenile offenders under their supervision or custody.

- Once both datasets are in place, KDOC and OJA need to cooperate to reach an agreement on how to share, stage, and analyze their agencies’ data so the state can have a comprehensive dataset of its juvenile offenders.

- The Kansas Department of Corrections should develop a process to ensure judicial districts are using reinvestment grant funds on appropriate programs.

Agency Response

On January 8, 2020 we provided the draft audit report to the Kansas Department of Corrections and the Office of Judicial Administration. Their responses are below.

Agency officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- 2017 Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee Annual Report (November, 2017). The Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee

- 2018 Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee Annual Report (November, 2018). The Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee

- Crossover Youth Services Working Group Report (June, 2019). The Kansas Department for Children and Families