Reviewing Kansas’s Procedures for Election Security, Part 1

Introduction

Senator Dennis Pyle requested this audit, which the Legislative Post Audit Committee authorized at its April 22, 2022 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

The audit request included 5 questions. For reporting purposes, we divided them into 2 separate audit reports. This report answers the following 3 questions:

- Do county election officers receive adequate training to administer federal elections?

- How do Kansas’s practices for maintaining, using, and sharing ballot images and cast vote records compare to other states’ practices?

- What policies and practices do the Secretary of State and county election officers have to protect the integrity of voting for long-term care facility residents?

We focused on the 2022 elections when answering these questions. We reviewed state and federal requirements. We also talked to officials and reviewed documentation from the Secretary of State’s office, 8 judgmentally selected Kansas counties, 7 judgmentally selected long-term care facilities, 5 judgmentally selected states, and several national organizations, such as the National Conference of State Legislatures. As part of this work, we surveyed 98 county election officers and interviewed 15 of them. Finally, we talked to and reviewed documentation from citizens concerned with election integrity.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives and any limitations on our ability to answer the audit questions. In this audit, we evaluated the Secretary of State and select counties’ controls for ensuring proper training. Through that work we found that neither the Secretary of State’s office nor 1 county tracked training attendance. Those issues prevented us from answering the audit question about training adequacy as described more later in the report.

In this audit, we also talked to select counties about their controls for preventing fraud and undue influence in long-term care facilities. Our work is limited to describing those controls. We were not able to evaluate them.

Legislative Post Audit Committee rules require us to report when an agency fails to respond to a recommendation or responds negatively. The Secretary of State’s office rejected our recommendation.

County election officers told us they felt prepared to oversee elections, but we couldn’t verify training for officers or workers because this generally isn’t tracked.

Background

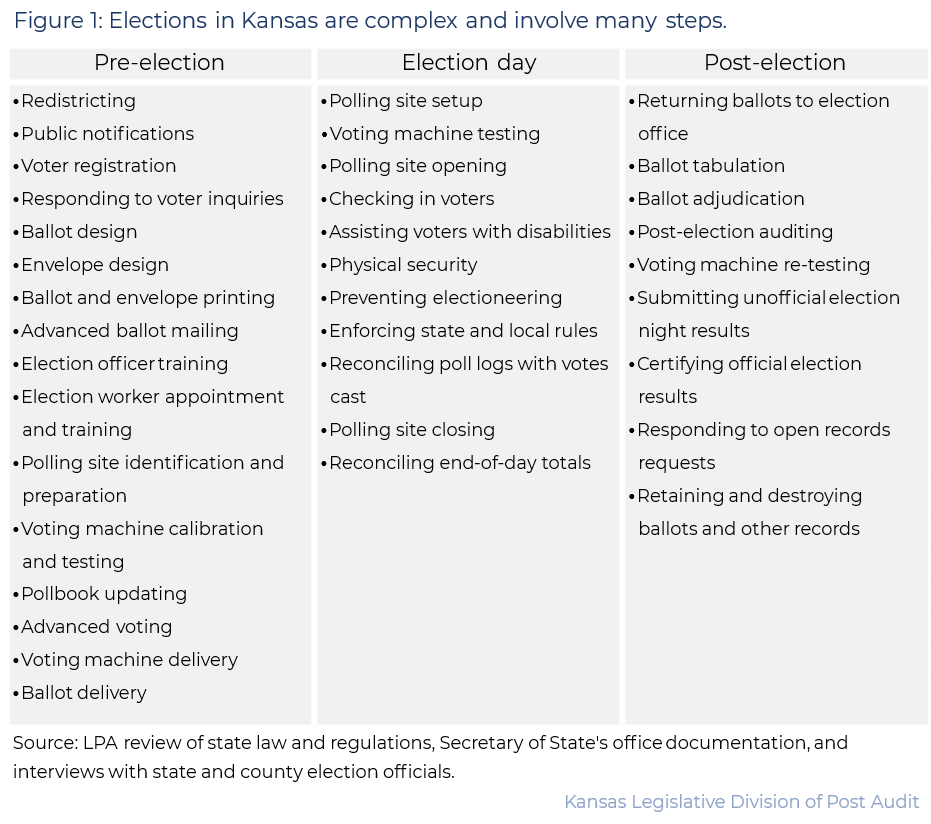

Elections are complex and require lots of people and processes.

- Operating and overseeing an election requires many people and processes working at different times and locations. Figure 1 lists the major steps necessary to run an election. As the figure shows, dozens of things must happen before, during, and after election day for an election to run smoothly.

- For instance, county election officials must design and print ballots prior to elections. This requires them to account for things like redistricting, variations across precincts, rotating candidates to appear in different orders, and translating the ballot into Spanish if required. Some county election officials must prepare hundreds of distinct ballot styles for a single election.

- The time constraints put on election processes compound this complexity. All these steps must take place within specific weeks, days, or hours. For example, state law (K.S.A. 25-106) says the polls can only be open on election day for a maximum of 14 hours.

- Successfully running and overseeing such complex processes requires preparation. Training election officials to do these things in alignment with state law and regulations is important for ensuring elections run smoothly and accurately reflect the will of the voters.

Each of Kansas’s 105 counties has a county election officer responsible for overseeing all elections in the county.

- In 101 counties, the elected county clerk is the county election officer. This is on top of their non-election duties, like county payroll and tax assessments.

- State law (K.S.A. 19-3419) requires the Secretary of State to appoint election commissioners in counties with populations over 130,000. Johnson, Sedgwick, Shawnee, and Wyandotte counties have election commissioners. This commissioner serves as the county election officer. They don’t have non-election duties like county clerks do.

- County election officers oversee all aspects of elections in their counties. For instance, they maintain voter registrations, accept candidate filings, appoint election workers, choose polling places, and certify county election results.

County election officers appoint election workers who perform frontline election duties.

- County election officers rely on county election workers to help run elections. State law (K.S.A. 25-2808) generally requires each polling place to have 3 or more election workers. This includes a supervisor who’s responsible for overseeing the polling place and the other election workers.

- Election workers do the frontline work necessary to hold an election. They do things like open and close polling places, check voters in and assist them, and distribute and collect ballots.

Kansas’s Election Training

State law has almost no requirements related to training county election officers and workers.

- State law (K.S.A. 25-124) only requires county election officers to receive training relating to their duties. It doesn’t say what this training should cover, how much they should get, or how often they should receive it.

- The Secretary of State is responsible for determining this training’s content and delivery. Agency officials told us training is held annually at the Kansas County Clerks and Election Officials Association’s (KCCEOA) conference. They said this session often lasted about half a day and attendance was mandatory.

- Secretary of State’s office officials said the content of the annual training changed depending on current events. They didn’t intend for it to train county election officers to do the basics of their jobs. Instead, it’s meant to keep them updated. For example, the 2022 training materials covered legislative updates and the current LPA election security audit.

- Secretary of State’s office, county, and KCCEOA officials also told us county election officers sometimes attended other optional trainings, though they’re not required. Those optional trainings included things like a KCCEOA training for new county election officers that’s held every 4 years. They also included weekly conference calls with other county election officers led by Secretary of State’s office officials that they said covered things like election planning. 1 county official also said some county election officers had gotten training for a national election administration certification through the National Association of Election Officials.

- For county election workers, state law (K.S.A. 25-2806) requires only that county election officers provide them training before each election. State law (K.S.A. 25-2502) defines the primary and general elections as distinct elections. State law doesn’t say what this training should cover or how much workers should get.

- State law makes county election officers responsible for determining this training’s delivery and content. We looked at 2022 county training materials to better understand what counties did.

- The training materials the counties developed generally covered frontline election administration. They included things like opening and setting up polling places, checking in and assisting voters, operating voting machines, and sealing and returning ballots to the county election office.

- However, the counties we reviewed delivered their training materials very differently. For example, Johnson County produced a highly developed online video series available to election workers on demand. Chase County training was simply going over a 2-page briefing in the 30 minutes before the polls opened on election day. It covered how to check in voters and a few miscellaneous reminders, like not to promote certain candidates.

We couldn’t tell whether county election officers got adequate training because no one tracks this, and state law says very little about it.

- We intended to evaluate whether all 105 county election officers received adequate training by reviewing attendance records. Ultimately, we couldn’t determine if they received adequate training for 2 reasons.

- First, the training requirements for county election officers are so minimal we couldn’t define and measure adequacy. There aren’t any federal requirements or best practices, and state law (K.S.A. 25-124) requires only that county election officers receive training relating to their duties.

- Second, neither Secretary of State’s office nor KCCEOA officials tracked who attended their annual training session. Secretary of State’s office officials said they feel like they can’t require county election officers to do things like attend trainings because most election officers are elected officials who are independent of the Secretary of State’s office. They said there’s no punishment for not attending these trainings.

- Secretary of State’s office officials said they rely on county election officers to do what they need to learn to do their jobs. They see their annual training session as supplemental. But neither they nor anyone else can measure whether county election officers are adequately trained to oversee elections.

Some counties we reviewed trained all their election workers before the 2022 general election, but most either didn’t or couldn’t show they had.

- We intended to evaluate whether Chase, Douglas, Ford, Harvey, Jackson, Johnson, Riley, and Wyandotte counties trained their election workers before the 2022 general election. We judgmentally selected these counties because they varied in things like population and geographic location. We didn’t review the 2022 primary election because of time constraints. And we thought reviewing the general election would likely be enough to show whether there were problems. State law doesn’t include documentation requirements, but we hoped to see some evidence of election workers’ training.

- Harvey, Riley, and Wyandotte counties provided documentation showing they trained all their 2022 general election workers immediately before this election.

- But 2 counties didn’t train all their 2022 general election workers immediately before this election. State law (K.S.A. 25-2806 and K.S.A. 25-2502) requires that county election officers provide their election workers training before each primary and general election.

- 50 of 312 (16%) Douglas County workers weren’t trained before the 2022 general election. County election officials said 27 of these had been trained before the 2022 primary election. But 21 others were trained in previous years, and there weren’t training records for 2.

- 33 of 1,477 (2%) Johnson County workers weren’t trained before the 2022 general election. County election officials said 26 of these had been trained before the 2022 primary election. But 5 others had worked previous elections and may have received training in previous years, and 2 had never been trained.

- Not all these issues likely had the same impact. Workers without previous experience or training may be unprepared for their frontline election duties. And workers trained in previous years may not have gotten important updates. The impact is likely less for workers trained immediately before the August primary election because it was only 3 months before the general election.

- Finally, 3 counties either didn’t provide documentation about election worker training or gave us documentation we couldn’t confirm. This included Chase, Ford, and Jackson counties. These counties’ election officials said they trained their workers immediately before the 2022 general election. We hoped to see documentation verifying this, but smaller counties may be able to track their election workers’ training without it.

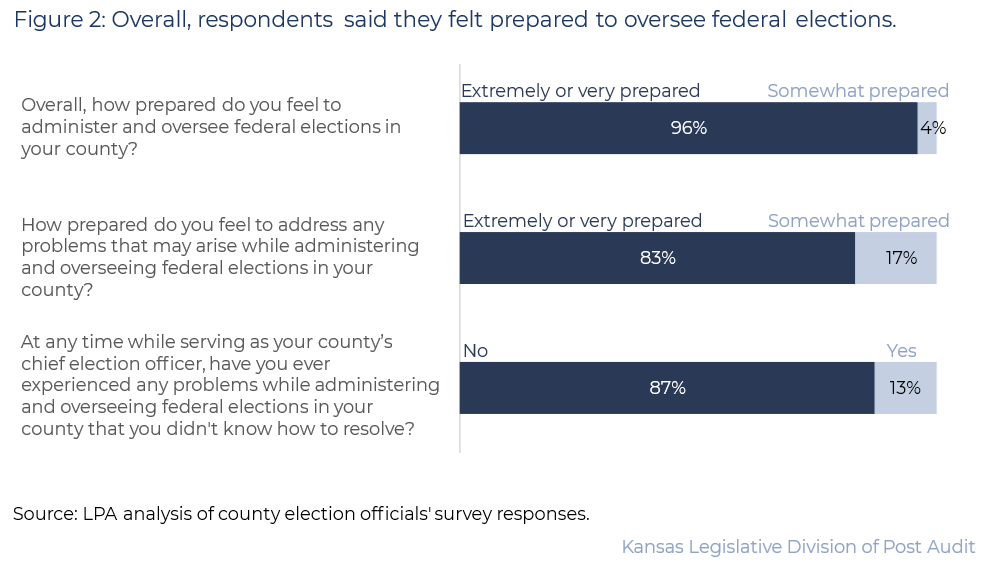

The county election officers we surveyed reported feeling well prepared to oversee federal elections.

- We surveyed county election officers to ask whether they felt prepared to oversee federal elections in their counties. We emailed our survey to all 105 of them, and 98 of them got the email. Of these 98, 76 responded (78%). Our results aren’t projectible. Many county election officers told us they currently feel under intense scrutiny from the media and the public. It’s possible this heightened focus on elections could have influenced their responses.

- Figure 2 shows survey responses related to whether respondents felt prepared to oversee federal elections. As the figure shows, 73 of 76 (96%) said they felt extremely or very prepared. But 13 (17%) said they felt only somewhat prepared to address problems that may arise during elections. 10 (13%) others said they’ve experienced a problem they didn’t know how to solve.

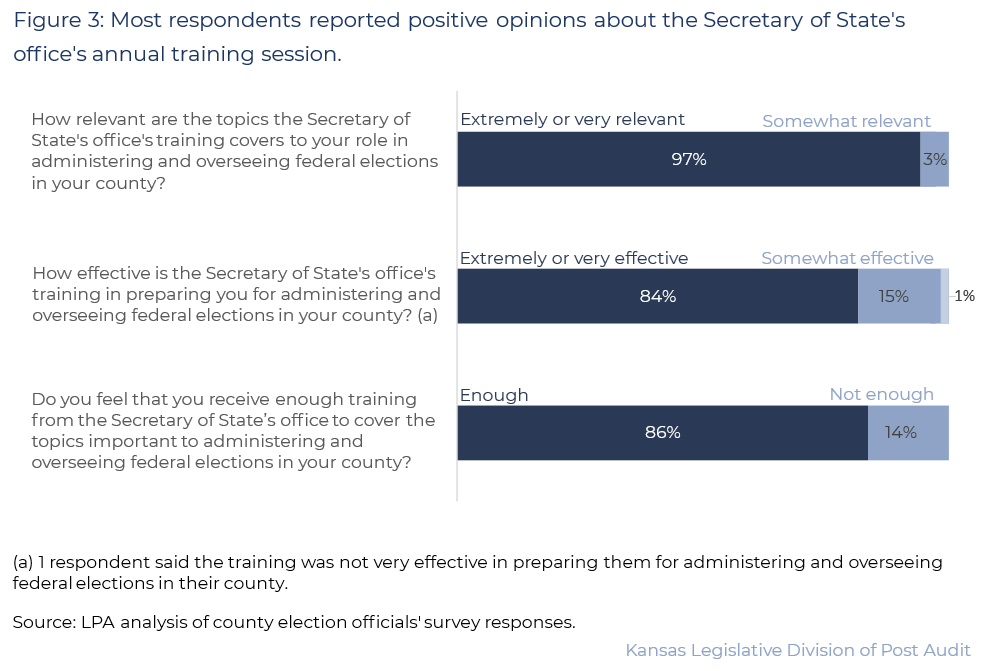

- Figure 3 shows survey responses related to the Secretary of State’s office’s annual training session. As the figure shows, 71 of 73 (97%) who reported receiving this annual training said it covered topics extremely or very relevant to overseeing elections. But 11 (15%) said this training was only somewhat effective, and 1 said it wasn’t very effective.

- Finally, 20 of 76 (26%) respondents said they got regular training from sources other than the Secretary of State’s office. They included election officials’ associations and voting machine vendors. 18 of 20 (90%) said this training covered extremely or very relevant topics. 16 (80%) said it was extremely or very effective in preparing them to oversee elections.

Some county election officers wanted different training or more help from the Secretary of State’s office.

- Many county election officers said they wanted more or different training from the Secretary of State’s office. For instance, a couple said the annual trainings are held in larger cities, burdening smaller counties’ election officers. They suggested webinars would be easier to attend. And a couple asked for more training on specific topics, like Kansas’s voter registration system.

- Secretary of State’s office officials said they’re developing a new statewide county election officer certification program. They anticipated it would begin in 2023 and require election officers to complete a series of courses. Several county election officers told us this will be a useful new resource. It’s still being developed, so we didn’t review any program materials.

- Some respondents wanted clearer statewide guidance. For instance, some asked for better information on state law and regulations, such as how to respond to open records requests. They said they’ve recently started getting lots of them but didn’t always know how to respond. Others said things like county election worker training manuals or calendars showing critical election dates would be useful.

Other States’ Election Training

Not all states we reviewed required training for county election officers, but those that did generally had more requirements than Kansas.

- We reviewed state law and talked to election officials from Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Missouri, and Utah to determine how their training requirements compared to Kansas’s. We looked at both county election officers and county election workers. We judgmentally picked these states because they had different training requirements.

- 3 of 5 states we reviewed required or incented election officers to receive more training than Kansas.

- Colorado required county election officers to complete a Secretary of State certification program with a specific format, curriculum, number of hours, and frequency. It included 14 initial core and elective courses covering topics like election security and public service. To maintain their certifications, county election officers had to complete at least 4 courses each year going forward.

- Maryland required county election officers to attend a statewide training every other year. The state didn’t require this training to be a particular format, curriculum, or number of hours. It often took up 1 day of the county election officers’ association’s annual conference. It recently covered topics like election security and legislation updates.

- Florida didn’t require county election officer training to be a specific format, number of hours, or frequency. However, it incented election officers to get an optional Secretary of State certification. Completing both initial and ongoing courses earned them a higher salary.

- Neither Missouri nor Utah had statewide training requirements for county election officers.

Most states we reviewed required training for county election workers, which some states were more involved in developing than Kansas.

- 3 of 5 states we reviewed were more involved and had developed more detailed requirements for county election workers than Kansas.

- Maryland required county election officers to administer county election worker training the State Board of Elections created. It covered frontline election duties like checking in voters, handling provisional ballots, and security awareness. County election officers had to train their county election workers before each election cycle and update them between the primary and general elections.

- Missouri required county election officers to develop county election worker training programs using curriculum the Secretary of State’s office created. It included a reference manual covering frontline election duties like setting up polling places and handling ballots. The Secretary of State’s office also provided county election officers guidance for providing effective training.

- Florida required county election officers to train their county election workers before each election. Polling place supervisors had to have 3 hours of training before each election. Other county election workers had to have 2 hours. The Secretary of State’s office also created a statewide polling place procedures manual covering 11 frontline election duties like operating voting machines and handling ballots.

- Colorado was like Kansas. Both required county election officers to train their county election workers before the first election they worked and again before each subsequent election. Both states’ officials said their state suggested training topics, such as new election laws. But county election officers were responsible for developing and delivering their own training.

- Utah didn’t have any county election worker training requirements. Utah officials told us they assumed county election officers trained their county election workers.

Kansas maintains and uses ballot images and cast vote records similarly to most other states we reviewed but is more restrictive than some about sharing them.

Background

Counties use digital scanners to record and tally voters’ paper ballots.

- Ballot images and cast vote records are created and stored by a voting machine called an optical scanner during the vote counting process.

- Voters’ paper ballots are fed through optical scanners after voters have made their selections. This happens either at each polling place or centrally in the county election office. The scanners automatically read ballots and tally how many votes went to each candidate. The scanners can create ballot images or cast vote records during these scans.

- County election officials combine all the county’s scanners’ vote tallies on a central election management computer. They transfer this information from the scanners to the computer using physical media, such as a USB stick. This computer shouldn’t be connected to the Internet and shouldn’t have other software applications on it. County election officials use this computer to determine the overall election results. And they can use it to view ballot images and cast vote records.

Digital scanners are also capable of producing digital copies of paper ballots that can be helpful during certain election processes.

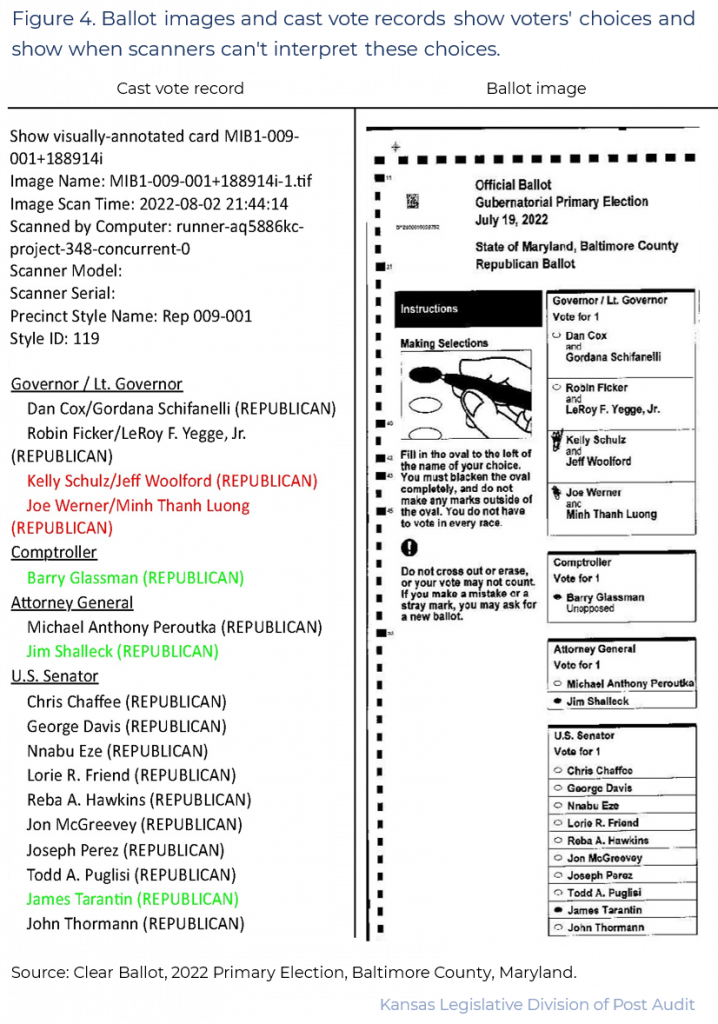

- Figure 4 shows parts of both a ballot image (on the right) and the related cast vote record (on the left).

- Ballot images are pictures of voters’ paper ballots, as the figure shows.

- Cast vote records are data files showing voters’ selections. They show how scanners read voters’ ballots and which candidates they selected. But they’re text files, not pictures. As the figure shows, they don’t look like ballots.

- When they exist, ballot images and cast vote records can be helpful for determining voter intent or auditing election results.

- County election officials can use ballot images to determine voter intent when scanners can’t. As Figure 4 shows, sometimes voters mark ballots incorrectly, such as with an X or by scratching out an unwanted response. In this instance, the scanner couldn’t understand which Governor and Lieutenant Governor candidates the voter intended to select. Officials could review the ballot image or the paper ballot to interpret the voter’s intent and count their vote accordingly.

- County election officials can also use ballot images to search for ballots from a specific voting location to help with post-election audits.

- And county election officials can compare ballot images and cast vote records to review how the scanner read the ballots and ensure it’s working correctly.

However, nothing requires county election officials to use digital copies, and not all scanners create them.

- Although they must select from a pre-approved list, county election officials have voting machine options. Optical scanners differ in terms of whether they can create ballot images and cast vote records.

- County election officials don’t always pay for ballot image or cast vote record functions. Even when scanners can create ballot images and cast vote records, sometimes vendors charge extra for them. County election officials don’t always think these functions are useful enough to be worth the price. For instance, 2 of the 6 counties we reviewed had scanners that couldn’t create ballot images. 4 of these 6 counties had scanners that couldn’t create cast vote records.

- State law doesn’t require counties to use either ballot images or cast vote records, so they decide based on their needs. Things like the county’s numbers of registered voters or ballots it processes in each election affect this decision. For example, a county with a small number of voters may not gain much from having digital copies. Officials can easily review ballots by hand.

Ballot Image and Cast Vote Record Practices

The Kansas counties and 5 other states we reviewed generally used ballot images similarly, but some other states made them public and maintained them like paper ballots.

- We talked to election officials from Chase, Douglas, Ford, Harvey, Lincoln, and Wyandotte counties to determine how they maintained, used, and shared ballot images and cast vote records. We judgmentally selected these counties because their voting populations differed, and we expected they would do different things with digital copies of ballots.

- We also reviewed state law and talked to election officials from Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Missouri, and Utah to determine what they did either statewide or county-by-county. We judgmentally selected these states because they did different things with digital copies of ballots. Only Missouri didn’t do anything with ballot images.

- As far as maintaining ballot images, other states retained them as long as paper ballots, but Kansas county election officials said they retained them for varying lengths of time. State law (K.S.A. 25-2708) says Kansas counties must keep state and national ballots for 22 months, but it doesn’t address ballot images. So, 1 county we reviewed told us they maintained ballot images for 22 months whereas others said other things determined how long they kept them. For instance, some county officials said they kept them until their election management computers ran out of hard drive space or needed a software upgrade. Either could be longer or shorter than 22 months. The other 5 states we reviewed said they maintained ballot images for at least 22 months, just like paper ballots.

- Some Kansas county election officials told us they used ballot images for purposes similar to 4 of the 5 states we reviewed. Election officials from Harvey, Douglas, and Wyandotte counties said they used ballot images to determine voter intent when a scanner couldn’t interpret a ballot. Harvey and Wyandotte counties said they also used them for post-election auditing because it’s more efficient than searching through thousands of ballots by hand. This was similar to how Colorado, Maryland, and Utah used ballot images statewide and how Florida used them on a county-by-county basis.

- As far as sharing ballot images, some other states made them public or available, but Kansas county election officials whose systems created ballot images said they didn’t share them. State law only addresses paper ballots, but the Kansas county election officials we talked to said they treated ballot images the same. As such, county election officials held ballot images as closed records. Conversely, Colorado, Florida, and Maryland made ballot images public. Officials said they either put them in online databases available to the public or provided them through open records requests. Missouri and Utah didn’t allow ballot images to be shared.

Unlike the Kansas counties in our sample, a couple states used and shared cast vote records.

- Kansas county officials said they maintained cast vote records for varying lengths of time. This depended on things like their election management computers’ hard drive space or software upgrades. State law doesn’t address cast vote records, so it isn’t clear they should be treated like paper ballots. But other states’ election officials said they maintained cast vote records the same as paper ballots. They kept them for the same length of time.

- No Kansas county election officials said they used cast vote records, but other states were mixed. Colorado and Maryland told us they used them statewide for post-election auditing. For instance, they compared ballots to their cast vote records to review how the scanners read them. Both states said this makes this process more efficient. Like the Kansas counties we talked with, Florida and Missouri officials said they didn’t use cast vote records. Utah officials weren’t sure whether anyone there used them.

- No Kansas county election officials said they shared cast vote records, but some other states did. County election officials whose systems created cast vote records said they viewed them like paper ballots and held them as closed records. But Colorado, Florida, and Maryland made cast vote records public just like ballot images. Missouri and Utah didn’t allow cast vote records to be shared.

Kansas officials we spoke with noted the transparency benefits of making ballot images or cast vote records public but also had privacy and logistics concerns.

- Some concerned citizens want to review ballot images or cast vote records to conclude on election integrity.

- For example, some people would like to see ballot images to ensure ballots were counted correctly. They could compare the official totals with their own counts based on the ballot images. If ballot images and cast vote records were displayed side by side, they could compare these, too. But county election officials told us this could cause confusion. As Figure 4 shows, it’s not always clear what a voter intended if they filled out their ballot incorrectly.

- Some people would also like to see their own ballot images and cast vote records to ensure their votes were counted as they wanted. But voters’ names aren’t on their ballots or cast vote records. And it’s illegal to add marks to ballots, including any that might make the voter identifiable through a ballot image.

- We talked to election officials from Chase, Douglas, Harvey, Lincoln, and Wyandotte counties and the Secretary of State’s office about making ballot images and cast vote records public.

- All county election officials we talked to said making ballot images and cast vote records public may increase election transparency and public trust. Colorado officials mentioned this, too. But Secretary of State’s office officials said voters expect their ballots to be secret. Releasing images of them might make people feel their privacy had been violated. Agency officials said they get calls from voters who want assurance their ballots are secret.

- Most county election officials also said it would be logistically difficult to post ballot images and cast vote records online. They said many counties would need to buy upgraded voting machines because their current machines didn’t create these digital copies. And it would require transferring and storing large amounts of data, even for a single election. Colorado officials also noted the costs and technology requirements as drawbacks.

- 1 county election official said an online database of ballot images would need robust security. For example, it would be important to keep people from downloading, doctoring, and distributing ballot images that show something different from the official election results. And it would be important to redact any identifying information people may have illegally added to their ballots.

Facility and county election officials described having a few basic practices to protect voting in long-term care facilities.

Background

Kansas has about 700 long-term care facilities, such as nursing and assisted living facilities.

- We reviewed September 2022 data from the Department for Aging and Disability Services to determine how many long-term care facilities Kansas had. We also determined what kinds of residents they served.

- Kansas had about 700 long-term care facilities in September 2022. The most common type (41%) was nursing facilities, including mental health nursing facilities. These provided 24-hour care for people who couldn’t live independently. They also provided room and board.

- Assisted living facilities were another common facility type (21%). These provided group residential settings. Residents got private living spaces but may have needed help with things like dressing or bathing. They didn’t need nursing care.

- Kansas had other facility types, like intermediate care facilities or boarding care homes. We didn’t review these. We only looked at a few facilities, so we focused on the more common facility types.

The national literature on this topic is sparse and much of it is dated, but it identified a few practices to address fraud and undue influence.

- We reviewed national literature to understand long-term care facilities’ voting-related challenges and practices that might help. This literature came from sources like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, National Conference of State Legislatures, U.S. Election Assistance Commission, and U.S. Government Accountability Office.

- The national literature on this topic is sparse and much of it is dated. However, it identifies a few key challenges long-term care facility residents face. According to national literature, residents may have physical or cognitive impairments (e.g., dementia) that mean they need help voting, such as requesting or filling out mail-in ballots. Further, they may have limited access to information and may have few chances to talk or learn about candidates or issues with people outside their facility. These situations may give people a chance to commit fraud or try to influence facility residents.

- The literature suggests that improving residents’ voting access and access to information may help to address these challenges. For example, it suggests:

- County election officials could set up polling places in facilities. Or facilities could help residents find and travel to their assigned polling places. Both would likely help residents vote on their own, reducing the need for assistance.

- Long-term care facilities could allow residents to select their voting assistants. Residents would likely choose someone they trust and therefore may not feel unduly influenced. Alternatively, the literature says that county election officials could provide bipartisan teams to help residents vote. In either case, the literature recommends that facilities document who helped residents vote to increase transparency and accountability.

- Facility or county election officials could provide neutral information on candidates or issues. Or they could provide sample ballots before elections so residents can take their time considering how to vote and aren’t rushed on election day.

- Facility staff could be trained on how to talk to residents about voting. This could include topics like registering to vote, voting by mail, and meeting important deadlines. This may also help residents vote on their own.

Kansas has a few basic laws related to fraud and undue influence, but nothing specifically for long-term care.

- We reviewed state law and talked to Secretary of State’s office officials to determine what requirements Kansas has to protect voting in long-term care facilities.

- State law requires a few, very basic practices that may help prevent or minimize fraud and undue influence. Those requirements apply to voters both inside and outside long-term care facilities.

- State law (K.S.A. 25-1124 and K.S.A. 25-2909) says officials must let certain voters choose who helps them fill out their ballots. Or bipartisan teams must help them if they’re at a polling place. These voters include those with illnesses, physical disabilities, limited English proficiency, and in some cases those who are simply 65 or older.

- State law (K.S.A. 25-1124 and K.S.A. 25-2911) also says that anyone who helps a voter must document this. For voting by mail, they must also attest they didn’t influence the voter. This relies on the assistant telling the truth.

- Finally, state law (K.S.A. 25-2310) says county election officials must publish voter registration information. This includes important locations and dates, including how to vote by mail.

- Additionally, state law (K.S.A. 25-604 and K.S.A. 25-2812) allows county election officials to distribute sample ballots before elections and set up mobile polling places in facilities. For mobile polling places, bipartisan teams of county election workers would come to the facility and administer voting for the residents. State law outlines several privacy and security requirements for mobile polling places.

Facility and county election officials we talked to said they have some general practices to help protect voting in long-term care facilities, but very few specific practices.

- We talked to Ford, Lincoln, and Wyandotte county election officials and officials from 7 long-term care facilities to understand their voting-related practices. These facilities included 5 nursing and 2 assisted living facilities in Ford, Harvey, Lincoln, Miami, Sedgwick, and Wyandotte counties. 3 nursing facilities offered both types of care. We judgmentally selected these facilities from the counties we reviewed for other work. They varied in things like geographic location and the types of residents they served. We also tried contacting a few other facilities but didn’t get responses.

- Our work is limited to interviews with facility staff and county election officials and the processes they described. We didn’t evaluate and can’t conclude on whether the processes worked or whether fraud or undue influence occurred. Doing so would have required watching residents vote, a private activity. We also didn’t review other situations where fraud or undue influence could occur, such as with vulnerable people living with family outside of facilities.

- The long-term care facility officials we talked to generally relied on normal facility practices to facilitate residents’ voting. They had very few election-specific practices but said they met state law’s very basic requirements.

- For example, most facility officials said their residents largely voted by mail. Some facilities used the same practices as for any other mail residents received or sent, such as the same communal mailbox. They didn’t do anything different with mail-in ballots. But a couple officials said they hand-delivered completed ballots to the county election office.

- A few facilities said they employed social workers or other staff to help residents however they needed. This included help with voting if residents asked. But these staff weren’t specifically hired or trained for this role.

- Finally, the 2 assisted living facilities we talked to didn’t have any election-related practices. They said their residents lived mostly independently, so they left it to them to vote if they wanted to. These facilities offered general transportation services to their residents. They could use these services on election day, just like on any other day.

- The county election officials we talked to generally said they followed the very basic requirements in state law but didn’t use optional practices. For instance, a couple said they didn’t have enough election workers for things like mobile polling.

- Other election officials weren’t sure how the practices would work. For instance, 2 county election officials said they didn’t want to set up mobile polling places in long-term care facilities because they thought this would require opening them to the public as general polling places. But state law (K.S.A. 25-2812) only allows residents to vote at mobile polling places set up in long-term care facilities.

- Finally, several facility officials told us mobile polling would benefit their residents. It would give them a designated time and place to vote within their facility. And it would allow county election workers to assist residents, rather than facility staff who may not know election law. 1 facility official said their residents sometimes lost their mail-in ballots or asked facility staff how they should vote. Mobile polling places may help prevent these types of things.

Conclusion

Elections are complex processes, and Kansas has many statutes related to their administration and oversight. For this report, we didn’t review them all. Instead, we were directed to focus on 3 specific aspects of the election process. State law was either silent or high level in all 3 areas. County officials run elections, and the counties we reviewed handled things differently in some areas. Whether election processes should be more uniform statewide is a policy decision for the Legislature. Some states we reviewed had more detail and clarity in areas such as digital ballot copies and training, whereas others were more like Kansas.

Recommendations

- The Secretary of State should more proactively hold county election officers accountable for receiving annual training, which may include requiring and tracking training session attendance.

- Agency Response: While the Secretary of State’s Office agrees that county election officers should receive annual training, the Secretary of State’s Office has concerns with this recommendation. The Secretary of State’s Office recognizes and respects that county clerks are independent, elected officials. State law does not authorize the Secretary of State’s Office to exercise enforcement authority over county clerks in their role as county election officials and does not compel county election officials to attend in-person training. It is important to note that if a county election officer does not attend in-person training, it does not mean the training was not received. The Secretary of State’s Office currently works with county election officers who are unable to attend in-person training to ensure they receive and understand the material. Ultimately, tracking in-person training session attendance is not an indicator of whether training was received. Therefore, the Secretary of State’s Office will continue its current practice of proactively working with all counties to ensure they receive annual training without imposing an unenforceable requirement on an elected official to receive training. However, the Secretary of State’s Office will work to enhance training delivery to provide additional options for counties to receive required annual training.

- The Secretary of State’s Office notes that for counties that do not attend annual in-person training, the county election official generally notifies the agency in advance, and the Secretary of State’s staff contacts the county election official to provide and review the training material and ensure they have the opportunity to ask questions about the material. The agency is committed to developing additional ways to deliver training to county election officers, including webinar options.

- In addition to providing the statutorily required annual training, the Secretary of State’s Office works closely with county election officials to help them administer elections. This includes leading weekly conference calls with counties that can serve as informal training opportunities. For example, calls may 1) discuss time-sensitive election issues 2) review the election calendar and discuss planning for upcoming election activities and 3) provide time for Q & A for county election officials.

- In April 2022, the Secretary of State’s Office took the initiative to launch a certification training program to provide enhanced training to county election officers. The training, which will begin this year, will require participants to complete a series of classes covering many aspects of election administration, including voter registration list maintenance, security of election systems, ballot preparation, and poll worker training. Once a county election official has taken all the required courses, a county election official will achieve a certified election official designation. The Secretary of State’s office will provide the curriculum and trainers for this program.

- The Secretary of State’s Office strongly believes that county election officers, as independently elected officials accountable to the voters, are in the best position to determine what training and assistance they need to conduct their local elections. The agency is looking forward to working with county election officers to provide enhanced training through the certification program and intends to increase delivery options of annual training through webinars or similar options.

- The Legislature should consider amending state law to strengthen training requirements for county election officers and workers. It could do this by specifying minimum training requirements such as hours, frequency, or topics. Or it could do this by strengthening the Secretary of State’s role in setting, developing, and overseeing these requirements.

- The Legislature should consider amending state law to clarify how ballot images and cast vote records should be maintained and shared when counties choose to use them.

Agency Response

On January 20, 2023 we provided the draft audit report to the Secretary of State. Their response is below. They generally agreed with our findings and conclusions but rejected our recommendation.

We also provided the draft report to Chase, Douglas, Ford, Harvey, Jackson, Johnson, Lincoln, Riley, and Wyandotte counties. We didn’t make recommendations to the counties, so their responses were optional. Only Jackson County provided a response, which is included below.

Jackson County officials disagreed with how we described their training records. They provided documentation and video camera screenshots they said proved they trained all their election workers before the 2022 general election. We reviewed the information they provided but chose not to make changes. That’s because their documentation showed dates from 2021, the 2022 primary election, and the 2022 general election. As such, we couldn’t tell whether they reflected 2022 general election training. Similarly, we couldn’t tell whether the screenshots they provided showed a training session and if so whether all their 2022 general election workers attended.

Secretary of State’s Office Response

The Secretary of State’s Office appreciates the work of Legislative Post Audit in preparing the audit report reviewing Kansas’s procedures for election security, and their understanding of the impact of conducting an audit on county election officers during an election year. The agency offers the following comments on the LPA’s audit recommendations.

2. The Legislature should consider amending state law to strengthen training requirements for county election officers and workers. It could do this by specifying minimum training requirements such as hours, frequency, or topics. Or it could do this by strengthening the Secretary of State’s role in setting, developing and overseeing these requirements.

The agency appreciates the recommendation for strengthening the Secretary of State’s role in setting, developing, and overseeing county election officers training requirements. The agency notes that it is the prerogative of the Legislature to act on this recommendation. The agency encourages consideration of the following regarding current training:

- The Secretary of State’s Office selects annual training topics based on a number of factors, not limited to, current issues in election administration, timeline in the election cycle, legislative or regulatory changes, and experience and knowledge of clerks, with the intent of providing timely and practical training. A set curriculum could become quickly outdated if incorporated into statute and fail to provide the most timely and useful information to county election officers.

- In 2022, the Secretary of State’s Office identified a need to provide enhanced training for county election officers and initiated the development of a certification training program. Beginning in 2023, a multi-year county election office certification program will begin for county election officials. This program will offer a series of classes covering many aspects of election administration, including voter registration list maintenance, security of election systems, ballot preparation, and poll worker training. Once a county election official has taken all the required courses, they will achieve a certified election official designation. The Secretary of State’s Office will provide the curriculum and trainers for this program.

- The agency would welcome the opportunity to formalize and enhance existing annual training to ensure that it complements and provides a foundation for the certification training the agency will begin providing counties later this year.

- Finally, the agency recognizes that 101 county election officers are independently elected officials, fulfilling the role of county clerk in 101 counties. They have many responsibilities in addition to election administration, such as preparing and mailing tax statements, including revenue-neutral rate notices which are required to be sent as clerks are preparing for primary elections; serving as the clerk of the board of county commissioners, working with budgets of all local jurisdictions within the county, as well as many other duties that occur year-round regardless of the election calendar. The agency encourages recognition of these responsibilities and timelines when considering election training requirements.

3. The Legislature should consider amending state law to clarify how ballot images and cast vote records should be maintained and shared when counties choose to use them.

The Legislature recognized the need to clarify the treatment of ballot images and cast vote records (CVRs), and enacted legislation during the 2022 session. KSA 25-2912(a)(2), states that “the voting system shall not preserve the paper ballots in any manner that makes it possible, at any time after the ballot has been cast, to associate a voter with the record of the voter’s vote without the voter’s consent.”

Based on this legislative directive, the Secretary of State’s Office drafted regulations barring public release of ballot images and CVRs to ensure that a ballot that has been cast cannot be associated with the voter who cast the ballot. These regulations should go into effect in April 2023. This legislative and regulatory clarification to safeguard ballot images and CVRs provides assurance to voters that their right to vote a secret ballot is secured.

Jackson County’s Response

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- Assisting Cognitively Impaired Individuals with Voting: A Quick Guide (2020). American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging and the Penn Memory Center.

- Compliance with Residents’ Rights Requirement Related to Nursing Home Residents’ Right to Vote (October, 2020). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Elderly Voters: Information on Promising Practices Could Strengthen the Integrity of the Voting Process in Long-Term Care Facilities (November, 2009). U.S. Government Accountability Office.

- Knowing It’s Right, Part One: A Practical Guide to Risk-Limiting Audits (May, 2019). Jennifer Morrell.

- Preserving Voting Rights in Long-Term Care Institutions: Facilitating Resident Voting While Maintaining Election Integrity (2016). Nina Kohn.

- Serving Voters in Long-Term Care Facilities (October, 2008). U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

- Voting for Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities (December, 2013). National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Voting Rights for Residents of Long-Term Care Facilities (2022). National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care.