Reviewing Foster Care Case Plan Tasks and Permanency Outcomes

Introduction

Senator Oletha Faust-Goudeau requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its June 1, 2020 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- Do tasks included in foster children’s case plans appear reasonable and relevant to their successful reunification with their families and are they being completed by children’s parents?

- Do outcomes for children in foster care vary based on factors such as age, race, or ethnicity?

The scope of our work on the first objective included a review of a nonrandom selection of 48 foster children’s case files from 2016 through 2020. We reviewed children’s case files and parents’ case plan tasks related to reunification. We also interviewed case management staff and judges. Our scope of work did not include a review of tasks assigned to other individuals, such as foster parents. It also excluded tasks related to other outcomes, like adoption. We also didn’t evaluate DCF or court decisions to remove or reunify children.

The scope of our work on the second objective included a review of demographic and outcome data for about 28,000 children who entered foster care between 2012 and 2020. We ran a series of logistic regression analyses to see whether children’s demographic factors affected their foster care outcomes. We interviewed case management providers and reviewed literature to help explain the results.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report limitations on the reliability or validity of our evidence. In this audit, we couldn’t find evidence identifying children’s ethnicities in 15% of the files we reviewed. We think DCF data about children’s ethnicities is generally reliable. But we couldn’t always determine whether that data was correct.

Audit standards require us to report written communications about minor internal control deficiencies not included in the report. We communicated 3 issues to DCF and the case management providers in a separate management letter. We told them about the data issue related children’s ethnicities described earlier. We told them that some tasks weren’t written as specific as they should be. Finally, we told them about 15 cases where case plan meetings were held more than 200 days apart. They should occur at least every 170 days.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

Parents’ tasks for reunifying with their child were generally reasonable and relevant, and parents generally made progress on or completed their tasks.

Background

District courts decide when children enter and leave the state’s foster care system.

- The district court decides whether a child should be declared a child in need of care (CINC). As defined in K.S.A. 38-2202, a child can be declared a CINC for reasons like parental abuse or failing to attend school.

- When the court declares a child a CINC, the child is placed in the Department for Children and Families’ (DCF) custody and enters the foster care system. While the child is in foster care, the child and their family receive case management services. These services should address why the child became a CINC and help the child exit the system. During this time, the child may stay with relatives, a foster family, or in a place like a residential facility.

- The district court decides when and how a child leaves the foster care system. A child exits the foster care system by achieving a permanency outcome.

- Reunification (or reintegration) is when a child returns home to their parent(s). This is the preferred way for a child to exit foster care.

- Adoption is when another individual(s) becomes a child’s parent(s). A relative or an unrelated family could adopt a child. Adoption is the preferred permanency outcome when reunification isn’t viable.

- Guardianship (or custodianship) is when someone becomes a child’s caretaker and assumes some of the rights of a legal parent. This is the preferred outcome when neither reunification nor adoption are viable.

- Another planned permanency living arrangement, like emancipation, should only be considered when there are good reasons to reject the prior outcomes. This outcome is only for children ages 16 and older per DCF policy.

While in foster care, children have case plans that document their permanency goals and what they or others must do to achieve those goals.

- Both state and federal law require children in foster care to have a written case plan. Case plans are also called permanency plans.

- Case plans document a child’s permanency goal(s) (e.g., reunification or adoption). The plans explain what must happen to achieve that goal.

- A case plan includes high-level objectives that are broken down into specific tasks. An objective is a high-level goal that identifies what a child or their family is trying to do (i.e., what their permanency goal is). Tasks are the specific steps needed to achieve the objective. Parents, the child, provider staff, or others can be assigned tasks.

- For example, a child whose parents physically abused him may have an objective to reunify with his parents in a home free from physical abuse. The child’s parents may have tasks to learn appropriate discipline methods or take anger management classes.

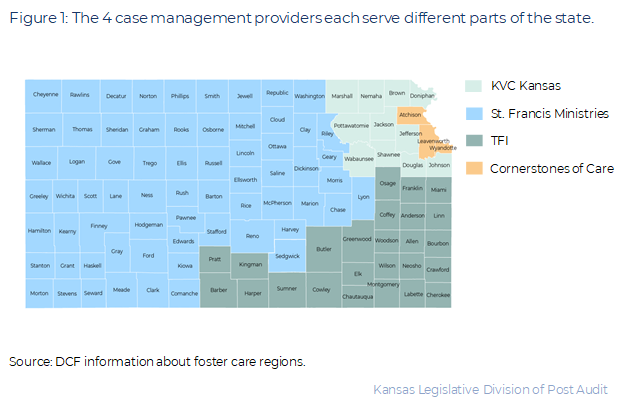

- In Kansas, private case management providers develop case plans and monitor progress toward case plan goals. DCF has grant agreements with 4 case management providers: Cornerstones of Care, KVC Kansas, St. Francis Ministries, and TFI. As Figure 1 shows, each provider covers certain regions. TFI and Cornerstones began providing services in October 2019. They took over regions previously served by KVC and St. Francis.

A case management team develops and monitors a child’s case plan.

- The case management team includes a case manager (a case management provider employee), the child (if 14 years or older), and the child’s parents. It may also include other parties, like attorneys, relatives, or guardians ad litem. Guardians ad litem are lawyers appointed to protect the interests of children in CINC cases.

- Under DCF policy and state law, the team must develop a case plan when a child enters the foster care system. The team should update the case plan at least every 170 days at formal case plan meetings. At these meetings, the team re-evaluates the plan and modifies it to fit the child and family’s needs.

- Regional DCF foster care staff review case plans for compliance with specific DCF policies and federal rules. They do not check whether tasks are reasonable and relevant.

Task Reasonableness and Relevance

We reviewed 48 children’s case files to see if the tasks assigned to their parents appeared reasonable and relevant.

- We used DCF data to select 48 children’s case files for review. Each child was declared a CINC in fiscal years 2016 through 2020. This was a nonrandom selection, so we cannot project our findings to the approximately 20,000 foster care cases from that time.

- Our selection included cases from all 4 providers and a mix of demographic factors. For example, we reviewed cases for children of all ages. We also reviewed cases involving children with White, Black, or Hispanic backgrounds. All cases had reunification as a goal.

- Because of the audit scope, we only evaluated tasks assigned to parents that related to reunification with the child. That’s because it’s generally the parent(s) who must complete tasks to reunify with their child. We didn’t review tasks related to other people or to other goals, like adoption.

Determining whether tasks were reasonable and relevant required significant professional judgment.

- There are no clear criteria for evaluating whether case plan tasks are reasonable or relevant to the case plan goal. The terms aren’t defined in state law or DCF policy, and people’s interpretations are subjective. What one person considers reasonable and relevant someone else may not.

- We interviewed DCF staff, the case management providers, and 6 district court judges to get their opinions on what tasks should be in case plans and why. We also reviewed DCF policies. Then, we surveyed case managers assigned to 23 of the cases we reviewed to learn why they included specific tasks in those cases.

- We used those interviews, policies, and our professional judgment to define “reasonable” and “relevant.”

- We determined tasks were reasonable when they reflected appropriate expectations. In other words, tasks weren’t overly burdensome or excessive. For example, a task for a parent to have a clean and safe home would be reasonable. But a task for a parent to have an immaculate home or a home of a certain value would be unreasonable.

- We determined tasks were relevant when they addressed why the child was removed from the home or other risks to a child’s safety. For example, a parent’s drug use might put a child’s safety at risk, even if it’s not why the child became a CINC. Thus, we would consider a task for the parent to pass drug tests as relevant if there was evidence a parent used drugs.

- Case managers and judges must use their professional judgment to decide what tasks parents should complete. Going too far could place an undue burden on parents and limit families’ chances to reunify. Not going far enough could mean children return to unsafe homes or enter foster care again in the future.

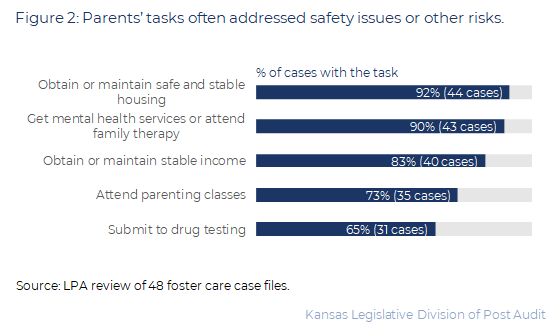

In the cases we reviewed, a parent had 11 tasks on average, mostly related to why children were removed or other safety risks.

- We reviewed about 670 tasks assigned to parents in the 48 case files we reviewed. 15 cases were open at the time of our review. It’s possible parents in those cases will get more tasks. Some cases also were open longer or were more complicated than others. This could have affected how many tasks parents had to work on.

- Parents were assigned a variety of tasks. About 530 tasks (79%) were substantive tasks meant to address safety issues or other risks. Figure 2 shows the most common tasks.

- About 140 tasks (21%) were administrative tasks like providing updated contact information and signing releases of information.

- As Figure 3 shows, a parent was assigned about 9 tasks on the first case plan, on average. This could be 9 tasks assigned to a single parent if a child had only one parent or if their parents were separated. It could also be 9 tasks assigned to both parents. Most parents weren’t assigned many more tasks in subsequent case plans. Only about half the cases had any additional tasks assigned. When there were additional tasks, there were only 2 to 3 on average.

Most tasks we reviewed were reasonable and relevant to children’s reunification with their families.

- About 90% of the tasks we reviewed appeared reasonable and relevant to the child’s reunification objective. We determined all 140 administrative tasks and about 460 safety-related tasks seemed reasonable and relevant because they addressed problems identified in the case files. For example:

- In 1 case, a child became a CINC due to physical abuse. The case file also identified concerns about domestic violence. In that case, a parent had tasks to complete a batterers intervention program assessment and to participate in family therapy.

- Another child became a CINC when their parent was arrested for drug possession. The parent had tasks to take a drug and alcohol assessment and to submit to random drug testing.

- About 10% of the tasks we reviewed seemed unreasonable or irrelevant. We thought about 70 safety-related tasks were unreasonable or irrelevant because we didn’t see any evidence there were problems for these tasks to address. Almost half of these tasks related to income, drug testing, or housing.

- Tasks related to stable income seemed unreasonable or irrelevant in 16 of the 40 cases (40%) they were in. In 1 case, parents had a task to maintain stable income. But there was no evidence there were issues with income. The case manager we surveyed also didn’t see income as an issue in that case. They didn’t think including this task was a problem because it shows there’s a safe environment for the child to return to. They also said it doesn’t take any effort to complete this type of task if the parent already has a stable income.

- Tasks related to drug testing seemed unreasonable or irrelevant in 9 of the 31 cases (29%) they were in. For example, 1 parent had a task to submit to random drug testing. But we saw no evidence that parent had a substance abuse problem. Further, the case plan said no one had concerns about substance abuse.

- Tasks related to safe and stable housing seemed unreasonable or irrelevant in 7 of the 44 cases (16%) they were in. For example, 1 child became a CINC for reasons unrelated to housing safety or stability. In that case, another child remained in the home. There was no evidence housing was an issue, but the parents still had a task to maintain stable housing.

- There weren’t patterns in the other tasks we thought were unreasonable or irrelevant. They were generally miscellaneous tasks that seemed to address problems that didn’t exist. For example, 1 parent had a task to avoid negative contact with law enforcement. But that parent didn’t have a criminal record or a history of such contact.

Unreasonable or irrelevant tasks didn’t seem to stop families from reunifying in the cases we reviewed.

- We didn’t think unreasonable or irrelevant tasks prevented families from reunifying. In the cases we reviewed, families reunified even when parents had unreasonable or irrelevant tasks. Cases that had other outcomes (e.g., adoption) didn’t seem more likely to include unreasonable or irrelevant tasks.

- 25 cases we reviewed ended in reunification. 14 of those cases (56%) included at least 1 unreasonable or irrelevant task.

- 8 cases ended in another outcome, like adoption or guardianship. 4 of those cases (50%) had at least 1 unreasonable or irrelevant task.

- The remaining 15 cases were ongoing at the time of our review. 7 (47%) included at least 1 unreasonable or irrelevant task.

- Unreasonable or irrelevant housing and income tasks don’t likely have many detrimental effects on parents. If parents already have these things, they don’t need to do anything. Other miscellaneous tasks like avoiding negative contact with law enforcement aren’t likely a problem for the same reason. But we don’t think parents should have these kinds of tasks because they address problems that don’t exist.

- Unreasonable or irrelevant drug testing could have detrimental effects on parents. This is because drug tests could be difficult for parents to get to if they have jobs or lack transportation. Courts also sometimes required parents to pass drug tests before visiting with their children. This may create an unnecessary barrier between parents and their children.

Parents’ Completion of Tasks

Parents often completed or made progress on their assigned tasks.

- We could not determine the percentage of tasks parents completed. This was partly because parents were often assigned ongoing tasks. For example, tasks to do things like attend therapy may not have a specific end date. Further, task completion wasn’t always clearly documented in case plans. We didn’t think this was a significant problem because progress toward reunification is reviewed at court hearings.

- Parents completed or made progress on their tasks in most of the cases we reviewed.

- Parents completed at least some of their tasks in 33 (69%) of the cases we reviewed. In 25 of those cases, parents reunified with their children. 5 cases were still open at the time of our review. In the remaining 3 cases, parents completed some tasks but didn’t reunify with their children. In those cases, issues beyond whether parents completed tasks seemed to affect the outcomes. For example, in 1 of these cases, the parent did not want to reunify with their child.

- Parents appear to have not completed any tasks in 14 (29%) of the cases we reviewed. 10 of those cases were still open at the time of our review. In some of those cases, parents either had made or may still make progress on their assigned tasks. For example, 1 parent had attended some parenting classes at the time of our review. But they still need to attend more classes and demonstrate what they learned for the task to be complete. We don’t know why parents in the remaining 4 cases didn’t complete their tasks, but it doesn’t seem to be because the tasks were unreasonable or irrelevant.

- 1 case didn’t have any tasks assigned to parents. The child’s behavior problem was the root issue. The child was emancipated.

Parents didn’t have to complete all their tasks to reunify with their children.

- In all 25 cases that ended in reunification, parents had ongoing tasks or other tasks to complete when they reunified with their children. For example, in 1 case, a child was reunified with their parent even though the parent hadn’t obtained a source of income. In another case, a child was reunified with their parent even though the parent hadn’t completed the assigned parenting class.

- Most case managers and judges we spoke with said parents don’t always have to complete all tasks to reunify with their children. They told us reunification may be appropriate when parents have addressed safety concerns, have a safe and stable home, and have shown behavioral changes—even if that means some case plan tasks are incomplete. They told us parents can finish some tasks, such as parenting classes or therapy, after they’ve reunified with their child(ren).

- But tasks that don’t need to be completed don’t seem relevant to reunification. At least one judge agreed with this idea. She said she’d question why a task would be on a case plan if a family can reunify without completing that task. This means some case plans could include fewer tasks while still allowing children to safely reunify with their parents.

Other Findings

Parents identified issues with their cases aside from the relevance and reasonableness of their tasks.

- We surveyed 11 parents to get their opinions about the relevance and reasonableness of their tasks. 5 were parents of children whose cases we reviewed. 6 were parents who complained to DCF, but whose children’s cases we didn’t review. We did not select these parents randomly, so we cannot generalize their experiences to all parents.

- The 11 parents we surveyed expressed several concerns.

- That DCF mishandled investigations.

- That caseworkers weren’t communicative (e.g., they didn’t respond to phone calls). A few mental health center officials we spoke with also said communication with caseworkers was an issue.

- That caseworker turnover was high and parents didn’t always know who their caseworker was.

- That scheduling certain appointments, like for mental health evaluations, took months.

- We didn’t substantiate parents’ concerns as part of this audit. That’s because doing so was outside the scope of our audit. But information from past audits and DCF’s case reviews support some claims parents made:

- DCF case reviews from 2016 through 2020 found visits between caseworkers and parents weren’t always adequate to promote achievement of case plan goals. Those reviews found visits were adequate in only 55% to 74% of cases.

- In our 2016 and 2017 foster care audits, we identified issues with high staff turnover rates and caseloads.

- In our 2018 mental health services in jails audit, community mental health centers reported barriers to adults accessing mental health services.

- These issues show parents may still face challenges when trying to reunify with their children. Their tasks may be reasonable and relevant. But that doesn’t mean those tasks are easy to complete. This may be especially true if it’s hard to access some kinds of services. And parents may not get enough support from caseworkers to complete their tasks.

Permanency outcomes for children in foster care varied based on demographic factors like age, race, and ethnicity.

Background

Children can leave the foster care system in 6 ways, which are called permanency outcomes.

- We looked at outcomes for all children who entered foster care between 2012 and 2020 and left foster care by January 2021. Our analyses included about 28,200 cases. Our analyses did not include children still in foster care.

- According to DCF data, there were 6 ways children could leave foster care. These are different from the permanency goals discussed in Question 1, but there is some overlap. A child wouldn’t have a goal to transfer to another agency, for example.

- Reunification is when a child goes back home to their parents. This is the preferred way for children to exit foster care.

- Adoption is when another individual(s) becomes a child’s parent(s). This is the next-most preferred way for children to exit foster care.

- Guardianship (or custodianship) is when someone becomes a child’s caretaker but not their legal parent. This is only preferred when reunification and adoption aren’t viable.

- Emancipation is when a child becomes legally responsible for themselves. It’s generally only allowed for children aged 16 or older. It’s also only allowed when the prior 3 outcomes aren’t viable.

- Transfer to another agency is when responsibility for a child moves to another agency. For example, a child could be transferred to the Department of Corrections or to a tribal court. The data we reviewed didn’t show what happened to children after they transferred.

- The “other” outcome captures other situations, such as when a child runs away or dies. We don’t discuss this outcome as part of our findings. That’s because we weren’t confident our analyses accounted for enough information to evaluate this outcome. About 1% of children had this outcome.

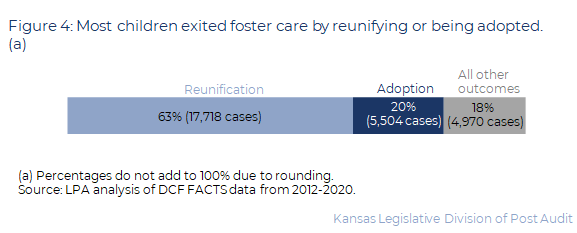

- Reunification and adoption were the most common outcomes. As Figure 4 shows, children reunified with their families in more than half of the cases in our analysis. About 20% of the cases ended in adoption.

Legislators expressed interest in knowing whether children’s foster care outcomes varied based on things like race or age.

- Children’s foster care outcomes may vary based on their demographics. For example, it could be that children of certain races or ages are less likely to reunify with their families. This could be cause for concern if reunification is the desired outcome. It could also mean children experience inequitable outcomes for reasons related to their demographics.

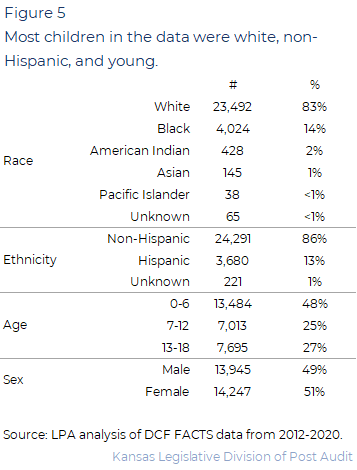

- We looked at 4 demographic categories: race, ethnicity, age, and sex. Figure 5 shows the demographic makeup of the foster children whose outcomes we reviewed.

- We can’t definitively say why there are relationships between children’s outcomes and their demographic factors. It could be that a demographic factor itself causes differences in outcomes. For example, race could directly cause differences in children’s outcomes because of biases. But race could also be linked to income, and it could be income that’s causing differences in children’s outcomes. Language in this report should not be taken to mean demographic factors are necessarily directly responsible for the differences in outcomes we identified. This work is an initial step in seeing whether factors like race or age affect outcomes and to what extent. We’d need to do more work to fully understand differences we identified. We’d also need to do more work to see whether those differences could be addressed.

Findings Related to Race

We used regression analyses to help us determine how specific factors like race or age affect children’s foster care outcomes.

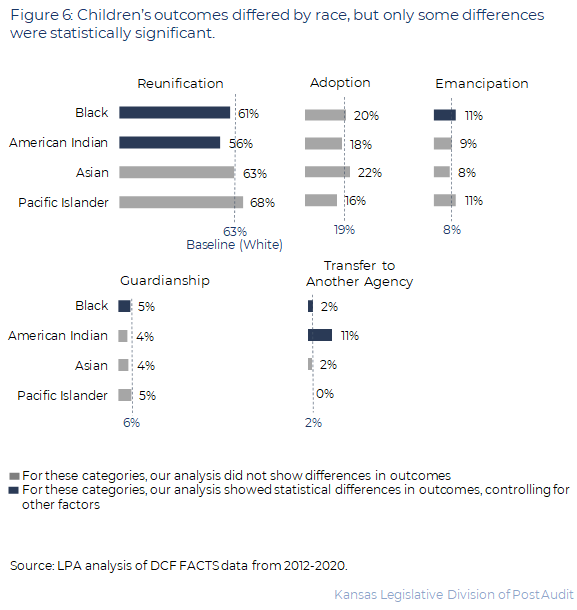

- We started by grouping children based on their demographics and looking at outcomes. Figure 6 shows actual outcomes for children by race. The figure shows how outcomes for children of 4 races compare to outcomes for White children. For example, Black and American Indian children didn’t reunify with their parents quite as often as White children.

- For each demographic factor, we had to pick one group to use as a baseline. For race, we used White children as the baseline because White children are most of the foster care population.

- The results in Figure 6 don’t tell us whether it was children’s races that were related to the differences we see. If Black children happened to simply be older than White children, it could be that age (and not race) were related to the differences we see.

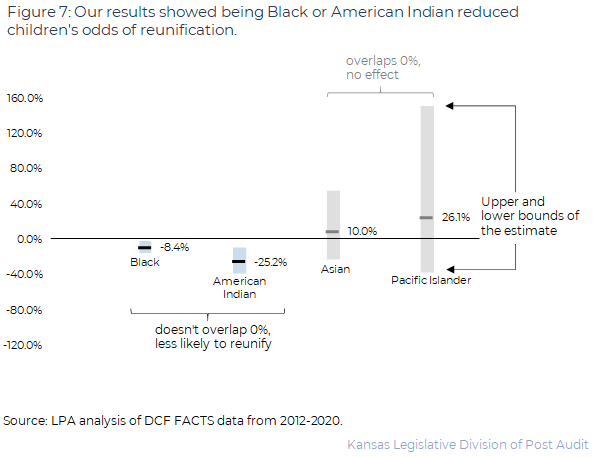

- We used regression analyses to isolate the effects of each demographic characteristic. For example, to compare outcomes based on race, we held things like age and sex constant. For multiracial children, our analysis used children’s first listed race. Figure 7 shows what this analysis revealed about how race affected children’s odds of reunification.

- The figure shows being Black or American Indian (in this report, this includes being Alaskan Native) reduced a child’s odds of reunifying with their parents by about 8% and 25%, respectively. The range of the estimate was small enough to be meaningful. In other words, being Black or American Indian had a statistically significant effect.

- The figure also shows being Asian or Pacific Islander (which includes being Hawaiian) didn’t have a clear effect on a child’s odds of reunifying with their parents. The range of the estimate was too large to be meaningful. In other words, being Asian or Pacific islander didn’t have a statistically significant effect.

- We used regression for each demographic factor we evaluated (race, ethnicity, age, and sex). This helped us determine how much each factor contributed to the outcomes we saw. In reality, of course, children are a combination of all of these factors. That’s why actual outcomes may be very similar even if specific factors (e.g., race or age) have a meaningful effect.

- To understand the relationships we saw, we interviewed the foster care case management providers and Dr. Becci Akin, a professor in KU’s School of Social Welfare, to get their perspectives. We also reviewed research publications and reports from the Children’s Bureau that discussed how demographic factors affect groups’ experiences with foster care.

Black children had outcomes similar to White children, but our regression analysis showed that being Black had a meaningful effect on several outcomes.

- As Figure 6 shows, Black children’s outcomes differed only slightly from White children.

- Despite only slight differences in actual outcomes, our regression showed that being Black had a statistically significant effect on 4 outcomes. Holding all other factors constant:

- Being Black decreased a child’s odds of reunifying with their parents by about 8% relative to being White.

- Being Black decreased a child’s odds of entering a guardianship by 23% relative to a White child.

- Being Black increased a child’s odds of emancipation by 34% relative to a White child.

- Being Black increased a child’s odds of transferring to another agency (e.g., the Department of Corrections) by about 28% relative to a White child.

- By contrast, our regression work did not show being Black affected a child’s odds of adoption. We didn’t identify statistical relationships between adoption and any of the races in our analysis. That could be because race isn’t related to different outcomes for adoption. Or it could be the data didn’t include information we’d need to discern a relationship. For example, if children of certain races were adopted less often than they could have been because adoption was never a goal.

- Dr. Akin and the case management providers we interviewed said Black children may experience different outcomes because of bias, mistrust in the system, and lack of resources.

- They told us Black children and families are held to higher, more stringent standards. A 2016 publication from the Children’s Bureau supported this idea. It said parties in the child welfare system may let biases influence their judgments. For example, it cited two studies showing Black families were more likely to have their children removed. This was even though case workers didn’t perceive Black families to have more safety risks. Some providers identified a need for more cultural awareness training and outreach.

- A couple of providers told us some Black families don’t trust the foster care system. This could make Black families less willing to engage with foster care services. It might also make Black individuals less willing to serve as placements or guardians for Black youth.

- They also told us a lack of resources may make it harder for Black families to reunify. One provider told us many Black families face poverty or have limited access to services. A 2003 publication from the Children’s Bureau identified similar issues. For example, it said Black parents often lacked information about how the child welfare system works. It also said they lacked financial resources to navigate the system (e.g., by hiring an attorney).

American Indian children were less likely to reunify with their parents and more likely to transfer to another agency than White children.

- As Figure 6 shows, American Indian children were reunified with their parents 56% of the time, whereas White children were reunified 63% of the time. Moreover, American Indian children were transferred to another agency 11% of the time compared to 2% for White children.

- In addition, our regression work showed that being American Indian had a statistically significant effect on certain outcomes. Holding all other factors constant:

- Being American Indian decreased a child’s odds of reunifying with their family by about 25% relative to a White child.

- Being American Indian increased a child’s odds of transfer by 596% relative to being White.

- This is likely due to the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). ICWA requires CINC cases involving American Indian children to be transferred to a tribal court in some cases. For example, tribes can request transfers for American Indian children. The data didn’t make clear what happened to children after they were transferred. We therefore can’t say what permanency outcomes these children ultimately experienced.

Asian and Pacific Islander children had similar outcomes to White children.

- As Figure 6 shows, Asian or Pacific Islander had similar outcomes to White children. For example, Pacific Islander children were reunified with their parents slightly more often than White children (68% of the time compared to 63%).

- Our regression analysis showed that when there were differences in outcomes between Asian or Pacific Islander children and White children, they weren’t because of race.

- It’s important to note that our results are based on limited data. That’s because very few Pacific Islander children have been in DCF custody. There were only 38 in DCF’s data.

Findings Related to Ethnicity

Hispanic children had similar outcomes to non-Hispanic children, but ethnicity had a meaningful effect on several outcomes.

- A child’s ethnicity reflects whether they’re of Hispanic culture or origin. DCF’s data breaks out children into specific groups, such as Cuban or Puerto Rican. In our analysis, we simply looked at whether children had a Hispanic origin.

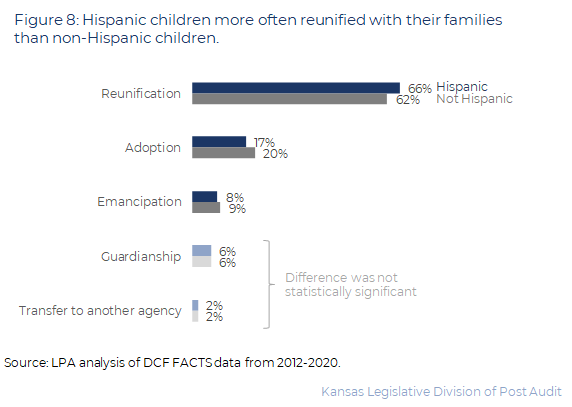

- Figure 8 shows outcomes for Hispanic and non-Hispanic children. As the figure shows, rates differed slightly for reunification, adoption, and emancipation.

- Despite only slight differences in actual outcomes, our regression showed that being Hispanic had a statistically significant effect on 3 outcomes. Holding all other factors constant:

- Being Hispanic increased a child’s odds of reunifying with their family by 20% relative to a non-Hispanic child.

- Being Hispanic decreased a child’s odds of being adopted by 17% relative to being non-Hispanic.

- Being Hispanic decreased a child’s odds of being emancipated by 16% relative to being non-Hispanic.

- Dr. Akin and the case management providers told us Hispanic families tend to have stronger community supports. Some providers told us families tend to be more likely to reunify when they have more support structures. A publication from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families reported Hispanic mothers are as likely or more likely than White mothers to have stable family lives during the first 5 years of their children’s lives. This may help explain why Hispanic children are more likely to reunify.

Findings Related to Age

The older children were when removed from their homes, the less likely they were to reunify or be adopted.

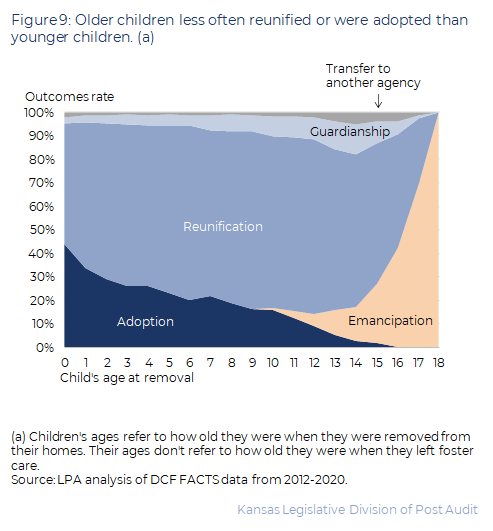

- As Figure 9 shows, children’s outcomes appear to vary based on the ages they were removed at. For example, younger children were adopted much more frequently than older children. Older children were emancipated much more often than younger children.

- Our regressions showed age affected all the outcomes shown in Figure 9. In other words, children’s ages had statistically significant effects on their foster care outcomes. In this case, our regression supported the conclusions one might draw by looking at children’s actual outcomes.

Outcome differences by age may be due to perceptions about children’s behaviors, their access to benefits, and their preferences.

- Some case management providers told us people like parents and foster placements have less tolerance for behavioral problems in older children. For example, when an older child acts out, people may see it as more dangerous than when a younger child acts out. They also said older children often have behavioral issues due to past trauma. Lack of tolerance for these issues may explain why older children are less likely to reunify with their parents or be adopted. It may also explain why they are more often emancipated.

- Two providers also told us children have better access to benefits if they are emancipated. For example, they told us children can get better access to medical services and financial assistance with college if they age out.

- Finally, Dr. Akin and two providers told us some older children may be resistant to permanency outcomes like adoption. For example, older children may not want to go through the process of building a relationship with a new family. One provider further told us some children may prefer to age out and then independently reunify with their parents.

Findings Related to Sex

Female children had similar outcomes to male children.

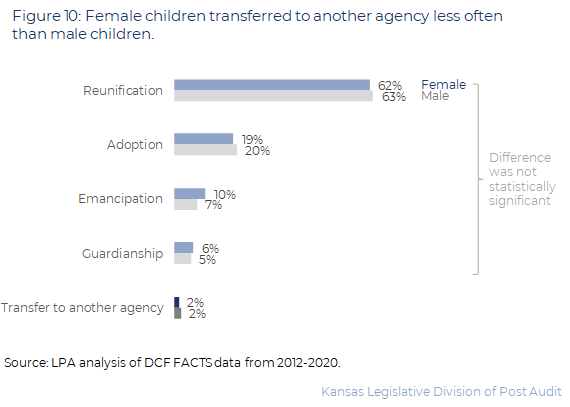

- As Figure 10 shows, male and female children experienced only slightly different outcomes.

- Moreover, our regression results showed sex only affected children’s odds of transferring to another agency. Our results showed being female decreased a child’s odds of transfer by about 36% relative to being male.

- Some case management providers said this could be because people judge male children more harshly when they act out. This could mean individuals in the foster care system are more likely to get law enforcement involved when male children act out. It could also mean male children receive harsher penalties when facing legal charges.

Other Findings

Black children were overrepresented in the foster care system and among children still in foster care.

- Black children represented a larger share of foster care cases than expected, based on U.S. Census Bureau data for 2019.

- Census Bureau data is for individuals who have only one race. In this section, the percentages we report cover only children who had a single identified race.

- According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Black individuals were about 6% of Kansas’ population in 2019. But Black children accounted for about 12% of the cases in the data.

- By contrast, White individuals were about 86% of Kansas’ population. White children accounted for about 78% of cases.

- DCF data for fiscal year 2020 shows Black children were about 2.5 times more likely to be removed from their families than White children. This corroborates that Black children are overrepresented in Kansas’ foster care system.

- Further, Black children were overrepresented among children who were still in foster care. There were about 6,500 cases in which children were still in foster care at the time of our analysis.

- Black children represented about 1,000 (16%) of the children still in foster care but only about 12% of all foster care cases.

- By contrast, White children represented about 4,800 (73%) of the children still in foster care but about 78% of all foster care cases.

- The case management providers and Dr. Akin said this could be because of Black families’ interactions with mandatory reporters. The 2016 Children’s Bureau publication identified a similar issue. When Black families experience poverty, they may make more use of social services. This increases their exposure to people who must report concerns about child abuse. If reporters have racial biases, they may be more likely to report Black families.

Conclusion

The Kansas foster care system is very expansive and complex. There are a lot of people and organizations involved, the process is very complicated, and a lot of discretion must be applied.

We don’t think it’s likely there are systemic problems with case plan tasks based on the results of our work. But it’s important to realize that case plan tasks are only a small part of the big picture. Moreover, because case plans are a key factor in parents being reunited with their children, even small problems can be a big deal. Parents are already under a lot of stress and trauma. So even the addition of one or two seemingly irrelevant or unreasonable tasks can feel overwhelming to parents. Moreover, the other systems these individuals often rely on (e.g., mental health centers) may also be overwhelmed and unable to provide quick support to parents.

We didn’t identify many significant differences in actual outcomes across the four demographics we looked at (race, ethnicity, age, and sex). Despite similar outcomes, our regression analyses showed demographic factors sometimes have a meaningful effect. This isn’t sufficient evidence to draw any firm conclusions. But it does highlight the fact that children may experience different outcomes (at least in part) because of their race or ethnicity. And that’s certainly worth further consideration of everyone involved in the foster care system.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On June 1, 2021, we provided the draft audit report to the Department for Children and Families, Cornerstones of Care, KVC Kansas, St. Francis Ministries, and TFI. Responses from DCF and TFI are below. DCF and TFI officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions. The other auditees chose not to submit written responses. Because we did not make any recommendations, auditees were not required to submit responses.

DCF Response

Dear Mr. Luthi:

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the draft performance audit report, Reviewing Foster Care Case Plan Tasks and Permanency Outcomes. We appreciate the time you and your colleagues devoted to this audit work. The performance audit addresses the following questions;

- Do tasks included in foster children’s case plans appear reasonable and relevant to their successful reunification with their families and are they being completed by the children’s parents?

- Do outcomes for children in foster care vary based on factors such as age, race, or ethnicity?

We are supportive of the report’s conclusions and we wish to acknowledge the receipt of the document and thank the Legislative Division of Post Audit for undertaking this important work. While the report does not provide any recommendations at this time, we would like to acknowledge the importance of continued racial equity exploration. DCF will continue to explore practices that promote improved outcomes and racial equity. We are partnering with the Kansas Strong collaborative to improve outcomes for children and families and the Change the World workgroup on Racial Disparities. We have expanded our efforts to include education and resources for all staff regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion training and crucial conversations on these topics. Lastly, DCF continues to monitor data and outcomes in an effort to identify factors which may impact children and family outcomes based on their demographics, race, and ethnicity.

Sincerely,

Laura Howard,

Secretary of Kansas Department for Children and Families.

TFI Response

Dear Mr. Luthi,

In response to the Foster Care Legislative Post Audit report, TFI supports the concerns about racial disparities as outlined in the written audit. TFI agrees that case plan tasks should be tied to the referral reason.

TFI appreciates the identification of the listed concerns, and we are actively reviewing steps our agency can take to continue our work in the foster care system.

We look forward to hearing the audit presentation at the Legislative Post Audit committee meeting later this month.

Sincerely,

Ashley Marple, LMSW

Vice-President of Performance and Risk Management

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- Case Planning for Families Involved with Child Welfare Agencies (April, 2018). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

- Children of Color in the Child Welfare System: Perspectives from the Child Welfare Community (December, 2003). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

- Family Stability and Instability among Low-Income Hispanic Mothers with Young Children (February, 2017). National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

- Racial Disproportionality and Disparity in Child Welfare (November, 2016). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau.

- United States Census Bureau QuickFacts: Kansas (July, 2019). United States Census Bureau.