Reviewing Foster Care Services for the Health and Safety of Children

Introduction

Representative Susan Concannon and Representative Jarrod Ousley requested this audit, which the Legislative Post Audit Committee authorized at its May 5th, 2021 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- Are foster care stakeholders following adequate policies and procedures to ensure the safety of children in foster care?

- Do foster care case management providers have sufficient capacity to provide necessary foster care services?

The scope of our work looked at the most recent grant period for DCF and its case management providers (October 2019 through present). Our scope only looked at safety and services for children in out-of-home placements (foster care). We did not include investigations of abuse and neglect, family preservation, or aftercare in our work. We also did not evaluate DCF or court decisions on the appropriateness of removal or reunification decisions.

We reviewed a random selection of 86 foster care case files from October 2019 through November 2021. The files are not projectable across the entire population of children in foster care in the state. However, the files generally represent the state’s foster care population. We reviewed the files looking for key safety processes such as required monthly worker-child visits. We used our professional judgment to determine if documentation of the visits was sufficient to prove the visits occurred and the child’s safety was effectively monitored. We also reviewed DCF and case management provider policies, statutes, and federal outcome reports. We interviewed stakeholders across various roles in the foster care system.

We also conducted separate surveys of case management provider staff and licensed foster homes. We asked both groups about the ability of case management providers and DCF to ensure the safety of children in foster care and the capacity of the state to provide services to those children. We sent the foster parent survey to most of the 2,600 licensed foster homes in 100 counties in the state. We sent the case management staff survey to all 600 foster care case management staff across all 4 case management providers. Response rates for both surveys were just under 40%. The results of the surveys are not projectable. However, the response rate is high enough and spread across the state enough to give us confidence that the answers from both groups represent systemic issues.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report limitations on the reliability or validity of our evidence. In this audit, we found reliability issues with DCF’s runaway and missing foster child data. DCF internal data varied significantly from their public runaway reports. We were unable to resolve these issues satisfactorily, but we were able to make general conclusions about DCF runaway and missing foster child policies and procedures.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. In this audit we looked at DCF and case management providers internal controls to ensure case files and reports are accurate and complete. We found case management providers follow their individual internal quality control process, but the controls are not always effective. We also found DCF has processes to monitor data and case provider performance.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

Although DCF generally has adequate written policies, DCF and case management providers’ practices were not adequate to ensure the safety of children in foster care in several areas.

Overview

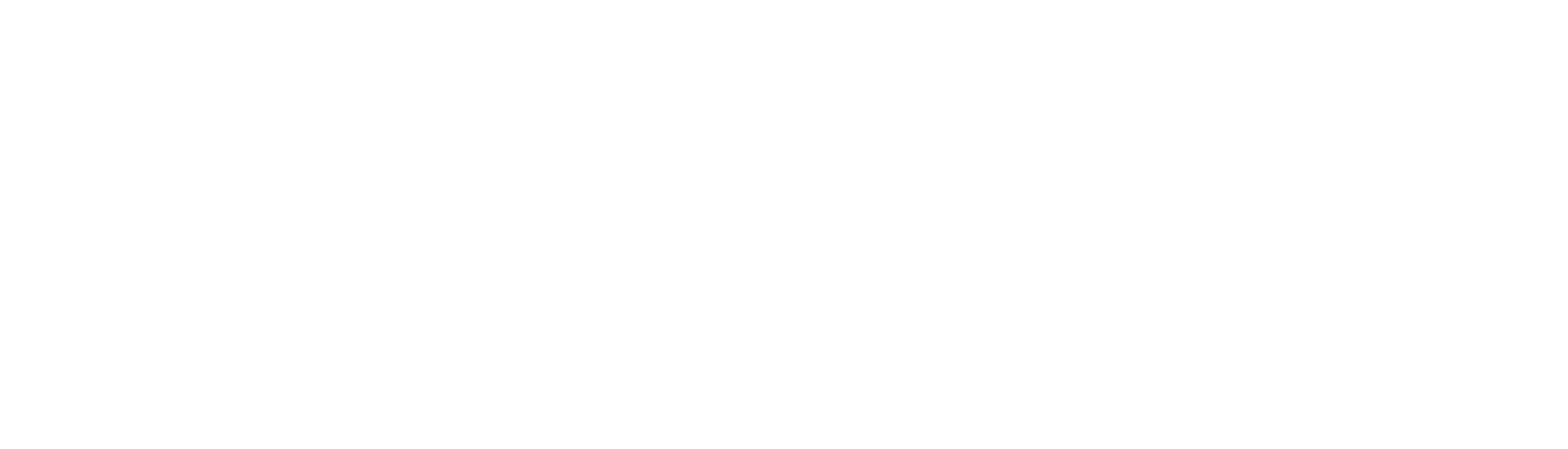

Many entities are involved in the foster care system.

- Figure 1 summarizes key entities and groups involved in the state’s foster care system and their roles. In this audit we focused on DCF and the case management providers.

- DCF receives and investigates all reports of abuse and neglect of children in the state. Sometimes law enforcement is also involved in the investigation. DCF makes recommendations to the court on whether to remove the child from their home based on the investigation’s findings.

- District courts then determine whether a child should be removed from their home and declared a child in need of care (CINC). Reasons for removal can range from abuse to neglect to truancy. When a child is declared a CINC, the court places them in the custody of DCF and they enter the foster care system. This typically includes an out-of-home placement.

- Once a child enters an out-of-home placement, otherwise known as foster care, DCF refers the child’s case to one of the private case management providers in the state based on the child’s location. Case management providers are responsible for monitoring the child and case progress. Case management providers may also coordinate with child placing agencies (CPAs) to identify a foster care placement for the child. CPAs are responsible for monitoring the foster home.

In fiscal year 2021, 4 case management providers served about 7,000 children in foster care statewide.

- The number of children in the state’s foster care system was just under 7,000 in fiscal year 2021. That is about a 10% decrease from fiscal year 2018. The number of children removed from their homes also declined from about 4,200 in fiscal year 2018 to 3,100 in fiscal year 2021. That’s about a 26% decrease. DCF told us these decreases are a result of their Family First efforts. Family first is a federal program that provides funding for services to families to keep children safely in their homes.

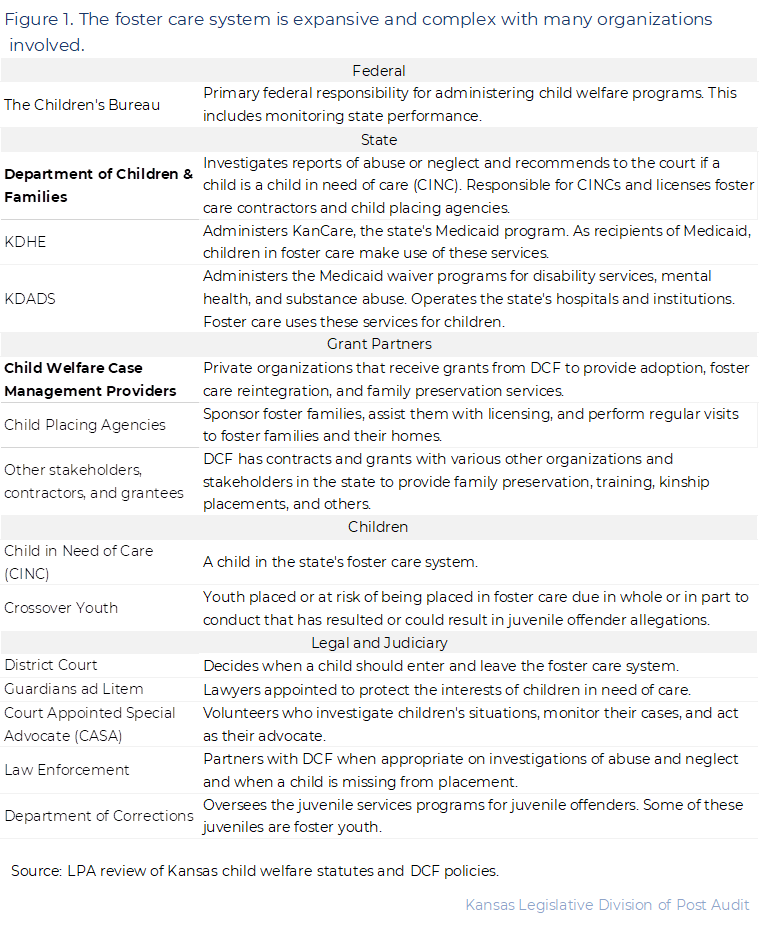

- DCF currently has grant agreements with 4 case management providers for foster care services: St. Francis Ministries, KVC Kansas, TFI, and Cornerstones of Care. As Figure 2 shows, each case management provider covers different regions of the state. The current grants began in October 2019 and will expire in June 2023. We collectively refer to the 4 organizations with grants as case management providers throughout this report. However, individual performance of the organizations may vary in the areas discussed.

- Since 2019, St. Francis has had the most foster care cases to manage (about 50% of all cases in the state). Comparatively, KVC and TFI each had about 20% of the state’s cases. Cornerstones of Care had the remaining 10% of cases.

- DCF uses state and federal funds to pay for the state’s foster care system. Total program expenditures increased from about $215 million in fiscal year 2019 to about $260 million in fiscal year 2020. Of DCF expenditures in fiscal year 2020, about 73% used state funds and 27% used federal funds. DCF attributes the increased expenditures to the new structure of foster care under the 2019 grants. In addition to having added 2 case management providers, DCF now determines how much foster parents are paid rather than the case management providers. Increased case management rates and money paid to foster parents account for most of the increased expenditures.

DCF monitors the foster care program at a high level, but case management providers determine how best to serve children in foster care.

- State law makes DCF responsible for the child and their safety while in foster care. DCF doesn’t provide foster care services directly though. Instead, DCF’s grant agreements with the 4 case management providers cover the foster care program. For its part, DCF establishes policies and monitors case management provider performance to ensure children in foster care are safe and making progress to permanency.

- Under the grant agreements and DCF policy, case management providers are responsible for:

- Finding a placement for children when they enter foster care,

- Conducting risk and safety assessments for children in care,

- Tracking and reporting case progress to the court,

- Coordinating worker-child and family visits,

- Making referrals to services and tracking them, and

- Maintaining documentation for the case.

- The case management providers determine how best to meet DCF policies and performance measures. Each case management provider has teams of case workers, support workers, and supervisors that handle the tasks for individual cases assigned to them. Many decisions in a child’s case are left up to case workers and other individuals close to a child’s case.

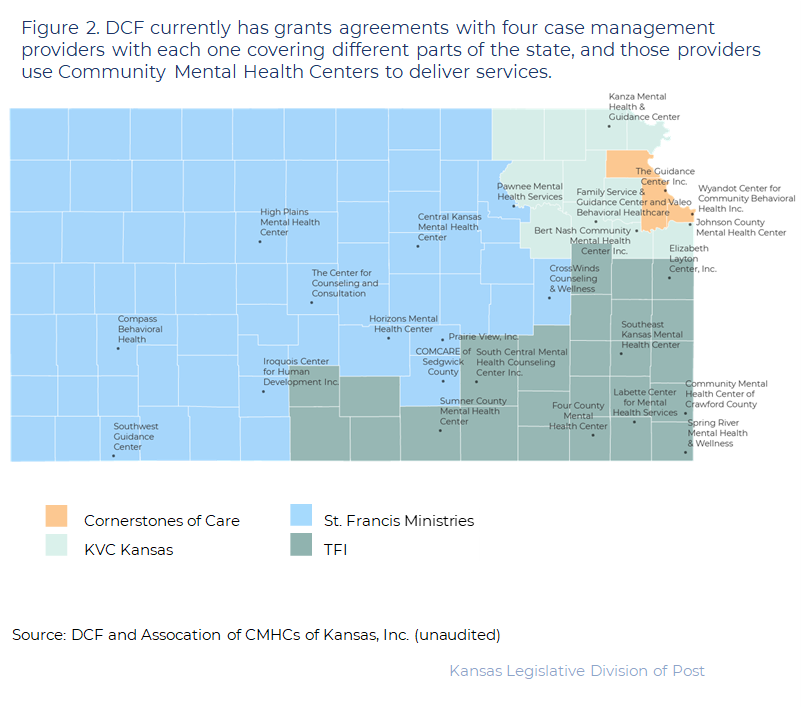

To assess safety of children in foster care, this audit examines several areas that we have audited in the past.

- LPA has conducted audits on child safety in the foster care system in 2016, 2017, and 2020. In those audits, we identified some issues with both DCF policies and performance. Those issues were related to things like the placement decision process, frequency and adequacy of monthly visits and safety monitoring, performance on federal safety and placement standards, and DCF monitoring of case management providers.

- In this audit, we focused our work on many of the same areas related to child safety in the foster care system:

- Placement appropriateness. A child in foster care should be placed with a family that can meet the child’s needs in the least-restrictive way.

- Child welfare workers’ routine in-home visits. The meetings should occur at least monthly and include private, face-to-face time with the child. At least 50% of those contacts must occur in the child’s foster home placement.

- Safety assessments. Child welfare workers should determine if the child is safe every time they have contact with the child through a formal or informal safety assessment.

- Safety issue response. For any emergency or incident of maltreatment of a child in foster care there should be a clear, consistent, and timely process to screen and investigate the incident. This should include conducting an abuse or neglect investigation if necessary.

- Foster parent training. This includes training on standards of care, methods of behavior management, and how trauma affects the children in their care.

- Figure 3 shows each of the areas we reviewed in this audit and how they compare to our findings from previous audits. As the figure shows, many of the problems we identified in this audit are not new.

- In this audit, we reviewed best practices related to the safety and well-being of children in foster care. The best practices we reviewed were from the Child Welfare League of America, the National Association of Public Child Welfare Administrators, the Center on Children and the Law, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We compared DCF policies, DCF staff practices, and case management staff practices to those best practices. We found DCF policies are generally adequate. However, DCF and case management staff practices were inadequate in several areas.

Placement Appropriateness

DCF’s policies appeared generally adequate to ensure children were placed in appropriate homes, but they could be stronger in one area.

- Best practice is that a child should be placed with a relative, kinship, or foster family that can meet the child’s needs. Case management providers should only place children with high health or mental health needs in the most experienced and well-trained foster homes.

- To determine the best placement for a child, DCF policies direct that DCF intake staff perform comprehensive assessments of the physical, emotional, developmental, and educational needs of a child along with a trauma history for the child. DCF then provides those assessments to the case management provider to help make placement decisions. DCF policy requires case management providers to place children in an appropriate home.

- DCF policy directs case management providers to find the most appropriate, least restrictive out-of-home placement for the child and consider the following factors:

- preserving the child’s racial, cultural, ethnic, and religious background,

- addressing the child’s safety, educational, physical, and mental health needs,

- placing the child close to their families and schools,

- placing the child with relatives or non-related kin whenever possible, and

- placing siblings together unless it is not in the best interest of the child.

- DCF policies are mostly adequate to ensure children in foster care are placed in homes that meet their needs but could be stronger. Best practice directs child welfare agencies to ensure that children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs only be placed in the most experienced homes. Further, state regulation requires that children in foster care be placed with foster families that have been assessed as appropriate to meet the child’s needs DCF policy only directs that placement considerations address a child’s safety, strengths, and needs.

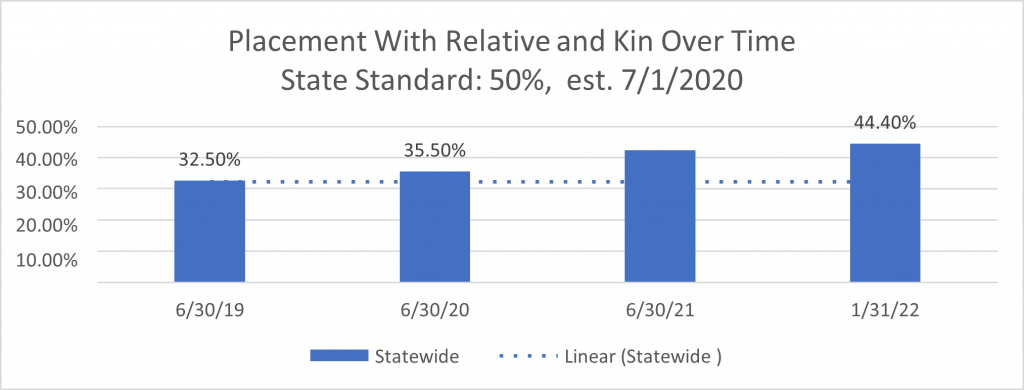

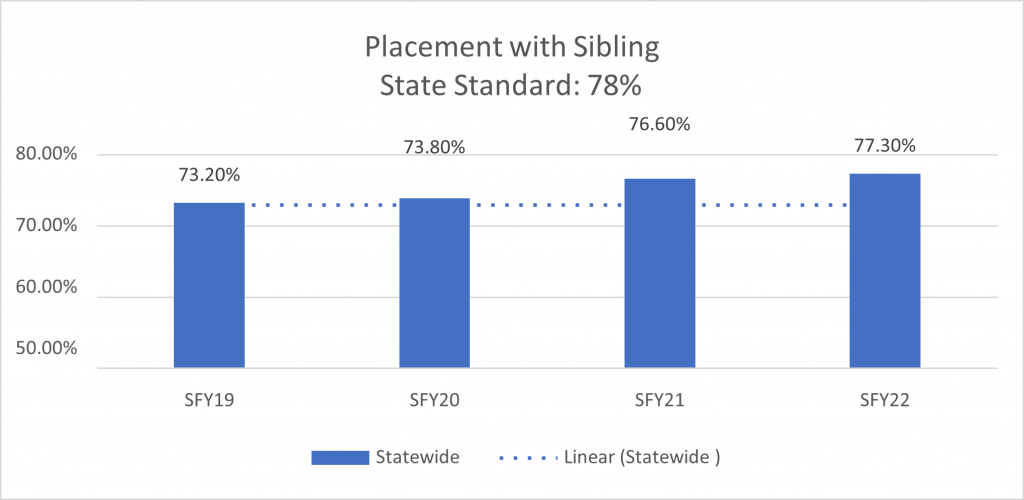

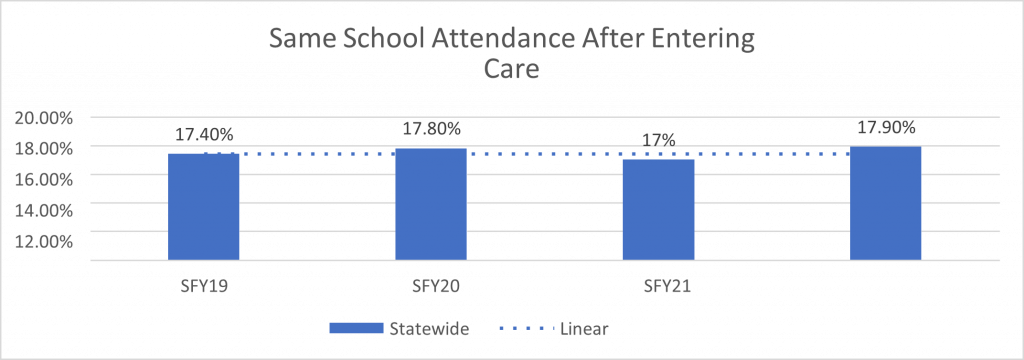

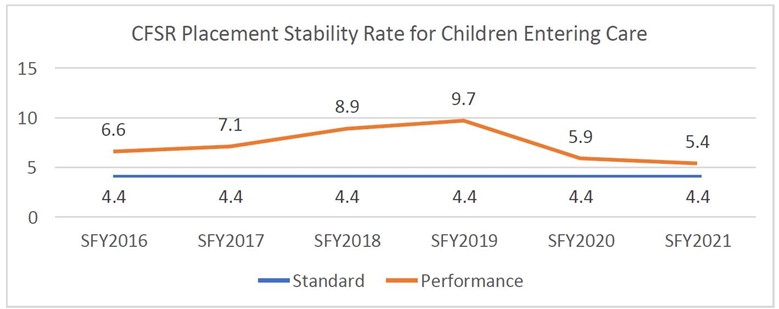

However, in practice, the case management providers did not meet some key federal and state grant safety and well-being standards related to appropriate placements.

- The federal Children’s Bureau and state grant agreements require states meet certain safety, well-being, and permanency outcomes for children in foster care. These include standards for the number of children in foster care who remain in the same school and are placed with siblings or kin.

- We reviewed case management providers’ performance on 5 federal and state grant safety and well-being outcomes related to placement appropriateness. Case management providers reconcile their performance data in their own systems and report it to DCF’s system of records (FACTS). DCF then gets all performance data for federal and state benchmarks from FACTS.

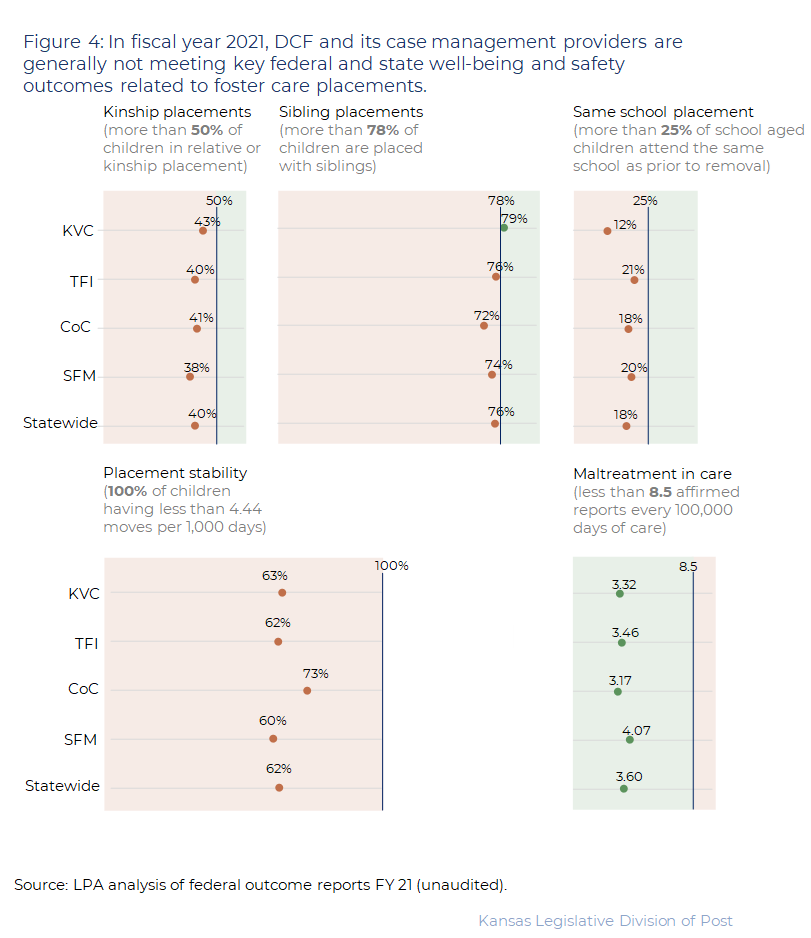

- Figure 4 shows the results of our review. As the figure shows, the state and its case management providers met federal outcomes for instances of maltreatment in foster care. However, case management providers generally did not meet other federal and state standards in fiscal year 2021.

- Not meeting these standards does not mean that children are unsafe, or that they are not in the most appropriate placements. But, performance on them may indicate process or capacity issues. Performance on these standards can also indicate child well-being while in foster care. For example, if a child can’t be placed with a relative or kinship placement, keeping a child in their own school while in foster care can help them stay connected to their community and family and reduce the overall trauma of separation from their family.

- Case management providers, however, are meeting federal standards for the number of incidents of maltreatment for children in foster care. The measure looks at the number of substantiated and affirmed reports of maltreatment involving children in foster care. The standard is no more than 8.5 affirmed reports every 100,000 days of care in a year. As the figure shows, all case management providers met this standard in fiscal year 2021. Case management providers have also shown some performance improvement under the current grants.

The federal Children’s Bureau has placed DCF on a performance improvement plan, but DCF has not penalized the state’s case management providers.

- States that do not meet federal standards are put on a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP), and DCF has been on a PIP since 2015. The PIP includes an annual review to measure agency performance in areas that needed improvement. Failure to improve could result in a loss of federal funding. Kansas has not lost federal funding because it has demonstrated improvement on its PIP since 2015. DCF was also on a PIP when we audited the foster care system in 2016 and 2017.

- Under the terms of the grants, DCF can penalize the state’s case management providers for poor performance, but it hasn’t. The original grant agreements did not specify what penalties look like. In the fall of 2021 DCF amended the grants to include specific incentives and penalties for performance. The maximum penalty is 2.5% of the grant’s expenditures. DCF officials told us that since 2019, they have not penalized any of the case management providers.

- DCF told us they have not used penalties because all the case management providers are now on performance improvement plans. These PIPs are separate from federal PIPs, and DCF establishes them to address case management provider performance. DCF officials and contractor staff emphasize a cooperative relationship between DCF and its case management providers. The PIPs case management providers are on include target performance goals and quarterly monitoring and discussions about performance results. Under DCF grants with case management providers, DCF may only penalize or terminate grants if the case management providers fail to meet agreed upon improvement goals.

Case management providers aren’t always using comprehensive data for making placement decisions.

- In a 2017 audit we found that case management providers, CPAs, and DCF did not share detailed information on foster homes with each other. We also found that case management providers may not have had all information about homes available in the state when they made a placement decision. The lack of comprehensive information on homes in the state meant that DCF couldn’t monitor if case management providers placed children in the most appropriate placement. The 2019 Legislative Foster Care Task Forced also raised this concern.

- DCF introduced the CareMatch database in October 2019 as part of their efforts to address recommendations from LPA and the Legislative Task Force. The database was meant to provide shared information on all foster homes in the state. DCF intended CareMatch to improve placement stability by making better first placements. It was supposed to match a child to available placements based on location, child characteristics, and placement preferences.

- DCF policies and grants require case management providers to use CareMatch if a relative or kin placement cannot be found. However, case management staff do not always use the CareMatch system. They told us they prefer to use their own systems, knowledge, and discretion to make placement decisions. CareMatch and case management providers’ systems do not speak to each other directly. So, case management providers and CPAs have to manually enter and reconcile their data about foster home attributes into CareMatch after already entering it into their own systems. This creates a duplicate data entry process.

- Case management officials told us their individual systems are more robust and have more informed data on families to make safe and appropriate placement decisions. For example, contractors collect information on families such as if a home is actively taking children, types of children they prefer to take including LGBTQ+, ages, sibling groups, and behavioral needs.

- Case management providers have rich information on homes in their network, but this is only a small portion of all available homes. There are 19 CPAs across the state for the 2,600 licensed foster homes.

- Because case management providers tend to rely on their own networks and homes, children might not be placed in the most appropriate home for their needs. This influences the stability of the placement. If a child’s placement isn’t a best fit for their well-being, the likelihood of moves increases.

- DCF is currently conducting feasibility work on a Comprehensive Case Management System that all case management providers would have automated access to. This would eliminate the need for case management providers to have to manually enter information from their system to DCF’s system. It also would ensure all data points CPAs and case management providers have on their foster homes would be accessible to other CPAs and case management providers.

Routine In-Home Visits and Safety Assessments

DCF policies were adequate regarding monthly visits between case management staff and children in foster care.

- Best practices and federal law about the safety and well-being of children in foster care state that child welfare workers should regularly monitor children in foster care through routine in-home visits. Those meetings should occur at least monthly and include private, face-to-face time with the child in their placement. Further, child welfare workers should determine if the child is safe every time they have contact with the child. They can do this through a formal or informal safety assessment.

- DCF policy requires visits between a case worker and child at least monthly. They also require at least 50% of those visits occur in the foster home. DCF adjusted the policy for COVID. For example, during March 2020, DCF paused all in-person visits and allowed case management staff to conduct virtual monthly visits (i.e., Zoom meetings with the child).

- DCF policies also require that the CPA sponsoring a foster home also perform monthly in-home visits to assess the child and the home for safety. This is another level of safety monitoring that is in place. We did not audit the extent to which these required visits were or were not happening.

- DCF policy requires that monthly worker-child visits include assessing the safety of the child. This includes observing any physical harm to the child, conditions in the home that might be unsafe, signs of emotional harm, or any other concern for a child’s safety and well-being. Policy also requires that all worker-child visits and safety assessments be documented for the life of the case.

However, in practice case management providers did not follow DCF policy related to frequency of in-home visits.

- To determine if case management providers followed DCF’s policies for monthly in-home visits and safety assessments, we conducted a random file review of 86 case files out of the state’s almost 14,000 foster care cases since October 2019. These files are not projectable to the entire population. The sample contained:

- 32 St. Francis files (37% of the sample)

- 21 KVC files (24% of the sample)

- 20 TFI files (23% of the sample)

- 13 Cornerstones of Care files (15% of the sample)

- Our file review focused on areas of concern from past LPA audits and stakeholders’ input. We evaluated the occurrence, sufficiency, and the quality of the documentation of monthly worker-child visits.

- We evaluated visits that occurred from October 2019 through late 2021. For each file we looked at 9 months of visits. This timeframe included the COVID-19 pandemic. DCF allowed Zoom visits during this time, so we adjusted what we qualified as an in-home, face-to-face visit as appropriate.

- This work showed that routine monthly visits did not happen as required.

- Federal standards require that monthly visits occur at least 95% of the time. Of the 86 files, 15 (17%) had more than one missed visit for their time in care between October 2019 and late 2021. 12 of those occurrences were in St. Francis files.

- Overall, we found 29 cases where a visit was missed (34% of the sample). St. Francis was responsible for 19 of the 29 cases with missed meetings. The other 3 case management providers each missed meetings on 2 (TFI), 3 (Cornerstones of Care), and 5 (KVC) of the cases.

- DCF also found that monthly visits do not always occur.

- DCF conducts quarterly file reviews. They review a random selection of files that are proportional by age and permanency goals to the overall population of children in foster care. DCF performance improvement staff with experience in child welfare use questions based on federal requirements to conduct the reviews for a 6 month period. This includes checking if child welfare workers made and documented monthly worker-child visits.

- DCF’s latest quarterly file review was July 2021 through September 2021. DCF staff reviewed 169 files across the case management providers and found 26 (15%) of those files generally had missed monthly worker child visits.

- We did not audit DCF’s file review, and we cannot confirm the reliability or accuracy of their results. However, they further show that monthly worker-child visits are not always happening as they should to ensure child safety.

- Many foster parents also told us monthly worker-child visits were not occurring.

- We conducted a survey of licensed foster homes in the state. We sent our survey to about 2,600 licensed foster homes in 100 counties in the state. This represents 96% of the licensed foster homes in the state. 959 people responded, a 37% response rate. We did not require respondents to answer every question. We asked them about the monthly in-home visits.

- Of 767 respondents who answered questions about monthly in-home visits, 212 (almost 30%) reported that case management staff missed at least 1 monthly worker-child visit in the period we reviewed. In most of those cases, respondents said staff missed 3 or more meetings during the time we asked about. Respondents reported that staff from all case management providers missed meetings.

- DCF policy requires worker-child visits occur in the foster home placement at least half the time. That means that some visits might be occurring elsewhere, for example, schools. Case management provider officials told us that foster parents might not know of those visits that occur elsewhere, which might contribute to the numbers foster parents reported to us.

- Worker-child visits are one of the main ways case management staff monitor the safety of children in foster care. Missed worker-child visits do not necessarily mean a child is unsafe. However, missed visits create a risk of serious harm to a child.

- Case management officials, staff, and stakeholders told us high caseloads, worker turnover, emergencies, miscommunication, and scheduling conflicts result in these missed worker-child visits.

Further, case management providers did not sufficiently assess the safety of a child in all cases.

- We reviewed monthly visits in 86 files to see if the child welfare worker sufficiently evaluated the child’s safety. We used our judgment of the documentation in the file to see if a safety check occurred during the visit, if the child was able to meet one-on-one with their child welfare worker, if the length and location of the visit was appropriate, and if there were any documented observations the child welfare worker made about child safety. We expected to see safety check boxes on the forms marked, detailed case notes, and follow-up actions on previous issues described.

- Case management providers either didn’t assess the child’s safety or didn’t sufficiently assess their safety in every month in 41 cases (48%) we reviewed.

- In 29 (34%) cases, child welfare workers did not conduct safety assessments. In these instances, the child welfare worker missed at least 1 monthly visit during the child’s time in care between October 2019 and late 2021. Of those missed visits, 19 were St. Francis Ministries cases; 5 were KVC cases; 3 were Cornerstones of Care cases; and 2 were TFI cases.

- In 12 (14%) cases, when a monthly in-home visit did occur each month, we saw evidence that case management staff did not adequately assess the child’s safety. Of those 12 cases, 4 were St. Francis Ministries cases; 4 were Cornerstones of Care cases; 3 were KVC cases; and 1 was a TFI case. In our judgement, the visit documentation did not indicate that the worker had spent time assessing the safety of the child as required.

- Additionally, in 6 (7%) of the files we reviewed we found insufficient documentation to determine if the worker had appropriately evaluated the safety of the child.

- We found 1 instance of worker-child logs having similar language from previous visits. This is an example of a worker copying the narrative from one monthly visit to another and was a problem we also found in our 2016 audit.

- DCF also found that the monthly visits case management staff conducted were not always sufficient to ensure child safety:

- As part of their quarterly file reviews, DCF checks whether issues related to the safety and well-being of the child were addressed. For example, they look if the visit addressed any services the child needed, if the case worker visited the child alone, and the length of the visit.

- In DCF’s July 2021 through September 2021 quarterly file review, DCF found that statewide worker-child visits were not sufficient in 76 (45%) of the 169 cases they reviewed.

- We did not audit DCF’s file review, and we cannot confirm the reliability or accuracy of their results. However, they do further indicate that case workers do not always sufficiently address safety and well-being when they see children.

- Case files are the main way case management providers document their efforts to monitor a child’s well-being and safety while in foster care. Incomplete, inaccurate, or insufficient documentation means case management staff may not have completed the visit. Children could be unsafe when visits don’t happen. Case management officials told us that they have found visits happened, but staff did not put in the time and effort for comprehensive documentation of the visit.

- Case management providers told us they have quality assurance processes to review documentation. However, these processes cannot work if case workers aren’t completing visits and safety checks.

- Stakeholders told us that high caseloads, inconsistency across case workers, and large amounts of paperwork prevent visits from being sufficient to monitor safety.

Urgent Response and Communication

DCF had adequate policies and grant requirements for responding to urgent matters.

- Best practices on the safety and well-being of children are that case management staff are available to foster families. Foster parents should have assistance available to them, including after-hours response during any time of crisis. Best practices also require child welfare agencies to conduct a formal review when certain incidents (child death or near death) occur. Those reviews are to evaluate systemic issues that lead to the incident of harm or potential harm.

- DCF’s policies and grants address urgent or emergency situations. These met best practices.

- DCF foster care grants require case management staff to have staff available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and respond to all urgent situations within an hour and document the response in the child’s file. An urgent situation may involve a child at risk or in the middle of mental or behavioral crisis, children missing from placement, situations where the child has or is at risk of harm or injury, and situations where the foster parent needs immediate assistance to maintain the well-being of the child. It’s important these responses happen quickly and consistently because a child’s safety is at risk.

- DCF policy also requires that case management staff report certain incidents to a team (e.g., abuse and neglect by a foster parent, child missing from foster care, or child death) within DCF. That team then will review the incident and determine what systemic issues might have contributed to it.

- DCF’s grants address general communication expectations for case management providers as well. These met best practices.

- The grants require case management providers to have a communication plan that demonstrates their ability to effectively coordinate and collaborate with community partners and families (birth and foster families). That plan must include a crisis hotline that is staffed 24 hours a day. Case management staff are responsible for giving families contact information for those communication and crisis services.

- The grants also require case management providers have a way to receive general complaints or concerns from families. Case management providers must provide a monthly report to DCF on the concerns and complaints they received, what steps were taken to resolve those issues, and the eventual outcomes. That process requires case management staff to respond within 1 to 5 working days from the date they received the concern, dependent on the severity and source of the concern. DCF can request a response time in less than the required 1 to 5 days.

However, foster parents complained about slow responses to urgent situations and poor communication in general.

- We surveyed most of the 2,600 licensed foster parents in the state and 37% responded. We asked them the typical amount of time it took to get a response from a case management provider in an emergency or urgent situation.

- Overall, 40 to 45% of foster parent respondents reported it taking more than an hour to get a response from someone on the child’s team, depending on the time of day they contacted them.

- Additionally, 4 to 7% of respondents said they never received a response from the case management provider during an urgent or emergency situation, depending on the time of day they contacted them.

- One foster parent reported, “We need . . . better emergency support help in off hours. We just had an emergency tonight about 5:00. It’s now 10:00 and I have yet to hear from a case team worker. Thank goodness the therapist answered her messages tonight.” Another simply stated, “After hours support from the case worker was not available.”

- Case management officials told us that communication breakdowns occur because staff is unavailable due to other job duties (e.g., in a court hearing) and foster parents are unsure of who to contact in a given situation (e.g. the crisis line as an option when they can’t get ahold of a child’s team members).

- Many foster parent respondents also reported not knowing who to contact with general concerns about their case management.

- 44% of respondents said they did not know who to contact at the case management provider when they have a concern about case management staff.

- 64% of respondents said they do not know who to contact at DCF if they have a concern with the case management provider.

- Foster parents reported their frustrations with the general lack of communication with case management staff. Comments we received included:

- “I can’t even express how bad communication is from my kids’ agency.”

- “Much of our frustration has come from lack of communication from the case team.”

- “Case workers are normally almost impossible to reach.”

- “The biggest issue is lack of communication.”

- Foster parents have multiple points of contact when there is an urgent matter. Under the terms of the grants, case management providers must have after-hour staff to respond to urgent matters. Case management provider officials told us that after business hours it is unlikely that a foster parent would be able to reach someone specifically assigned to a child’s case. Additionally, according to case management officials, CPAs also have a responsibility to provide timely responses to foster homes in an urgent or emergency situation. In situations where foster parents can’t get in contact with someone assigned to the child’s case, they need to be aware of how to contact after-hours staff, CPAs, and other crisis resources available to them.

- When we asked about these issues, case management officials reported that every case worker and support staff should provide their contact information to foster families. However, case workers frequently turn over. When this occurs, it is possible new staff contact information does not get provided to foster parents. Case management officials told us they have a process to ensure contact information is updated. For example, one case management provider is updating their process to include handing out magnets with all contact numbers to foster parents.

- Additionally, case management providers told us they have a process to receive and address complaints from foster parents, but those processes are not consistent across the case management providers. This limited our ability to evaluate how effective case management provider complaint tracking and customer service processes are.

- Some have a clear system that tracks resolutions of complaints as well. Others track complaints and resolutions at the case level and documentation is in individual case files. Still, others track complaints differently based on the type of complaint. For example, a complaint about a specific employee may be referred to the employee’s supervisor who would then address it through coaching. Those complaints or resolutions would be found in the employee’s records and performance evaluations.

Foster Parent Training

DCF policies on foster parent training were adequate.

- Best practices state that foster parents should receive adequate training. That training should include how to meet the needs of children in their care and the expected standard of care for children. Foster parent training also may include training on reasonable and prudent parenting, methods of behavior management, and how trauma affects the children in their care. Best practices from multiple organizations set pre-licensure training levels at 6 hours minimum.

- DCF policy says that all foster home applicants shall participate in preparatory training and all licensees must complete 8 hours of training each year. DCF also uses the Trauma-Informed Partnering for Safety and Permanency – Model Approach for Partnerships in Parenting (TIPS-MAPP) training curriculum for foster parents. This curriculum provides 30 hours of training to prospective foster and adoptive parents in the state using trauma-informed care. It is a training program used in multiple states. These standards and training program meet best practices.

- Training ensures that foster parents are prepared to meet the needs of children in care, which may be more complicated than children not in foster care due to their history. Foster parents who know how to meet the child’s unique needs help build a safe placement for the children in foster care.

Most foster parents report they have been provided with appropriate training.

- We focused our work on whether foster parents were satisfied with the training they received in specific areas. 959 out of 2,600 licensed foster parents responded to our survey.

- A majority (75%) of the foster parents who responded to questions about training said they had been provided with appropriate training to meet the needs of children in their care. The other 25% said they had not been provided appropriate training.

- Most survey respondents were also satisfied with training in the areas of childhood trauma, behaviors, emotional needs, mental health needs, development needs, cultural needs, gender identity or sexual orientation needs, and other unique needs.

- Foster parents told us that barriers they experience to receiving training included that training wasn’t at a convenient time or location, training wasn’t available on the topics they needed, training wasn’t offered, and that other obligations took priority.

Missing or Runaway Children in Foster Care

DCF had adequate policies to locate missing foster care children.

- Children entering foster care may be at risk to run from their placements due to histories of abuse and neglect, substance abuse, mental health diagnoses, and instability of placements. They often return to family and friends when they run. They frequently run because they cannot adjust to living under new circumstances or to leave a situation they feel unsafe in.

- Research shows that while absent from placement, children are at higher risk of being sexually or physically victimized, engaging in delinquent behavior, using drugs or alcohol, or being victims of human trafficking. Locating missing children quickly is therefore a key safety concern.

- We identified 6 best practices related to missing children. DCF’s policy addressed all 6 best practices. These best practices include:

- A child should be reported to law enforcement as a missing person immediately or within 24 hours.

- Reports to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) should also be filed within 24 hours.

- Case management staff should maintain regular contact with law enforcement and NCMEC while they attempt to locate the child.

- Case management staff should contact relatives, neighbors, teachers, or any other known close relations of the child to try to find them.

- Case management staff should check local emergency shelters, hospitals, and homeless children’s programs. They should also check the missing child’s social media accounts.

- Once located, case management staff should assess a child’s experiences while they were absent. This includes interviewing the child about their experience while missing from care and screening the child to see if they were a victim of human trafficking.

- When a foster parent or case management staff reports a child missing from a placement, DCF policy requires immediate engagement of their Special Response Team. The 12-member team is a statewide network of DCF and case management staff. The team works with children at risk to run, focuses on locating and recovering missing children, and assesses system improvements related to missing children.

- DCF’s Special Response Team policies align with best practices, including:

- Immediately reporting a missing child to law enforcement.

- Immediately notifying the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC).

- Continued follow-up with law enforcement while the child is missing.

- Assisting in contacting individuals who may have information about the child’s location, including friends, family, teachers, and others.

- Checking the child’s social media for activity indicating their whereabouts.

- When the child returns, an assessment that includes interviewing the child about their whereabouts, who they were with, why and how they left their placement, and if human trafficking victimization occurred. They will also create a safety plan after the child returns to reduce the risk of future incidents. This could include finding a more suitable foster home for the child’s needs.

It appears case management providers and DCF took appropriate action for runaway or missing children.

- There were 6 files in the 86 files we reviewed, which had incidents of runaway children from their foster home. We did not intentionally select these files but discovered them through our review. We reviewed them to determine the child’s outcome and if case management staff followed policy.

- In our judgement, case management staff took and documented appropriate actions to locate the children in the 6 cases. For example, they documented efforts taken each month a child was missing such as checking with relatives. They also worked with law enforcement to locate a child.

- Anecdotally, case management staff also told us that they believed the Special Response Team policies and positions were having a positive impact on their ability to find and recover missing children and prevent future children from running away. The Special Response Team is new with the current grants. The Special Response Team positions are strictly focused on working on issues related to run away and missing children from foster care and do not carry any other cases.

The number of children running away from foster care and recovered has been consistent in recent years.

- We analyzed DCF data to test if the new policies and procedures had an impact on the number of children running away from foster care and their recovery. However, we found discrepancies between DCF’s data on runaways from their system of record (FACTS) and daily public reports available on DCF’s website. DCF staff told us the FACTS data doesn’t have the entire population of runaway children from foster care and often has reliability issues. For that reason, we relied on the public reports, which case management staff report directly to DCF in real-time. We could not verify the real-time reports against the DCF system of record (FACTS) though.

- The number of children missing or runaway from foster care in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 has ranged from about 55 to about 80 per month:

- Across the 2 years, on average about 67 children in foster care were missing from their foster homes each month, with the range being anywhere from 55 to about 80 in each month. These numbers should be considered very fluid, though, because the number of children missing from care can change rapidly from day to day and month to month.

- Most runaway foster children were aged 16-17.

- Both females and males were represented equally, mostly proportional to the total foster care population.

- Children who have run away before are more likely to run away again.

- The largest concentration of runaways was in the Wichita area. DCF officials told us that this is because Wichita is a metropolitan area, which makes running from a foster home easier. It is much harder for children to run away when the nearest neighbor, family member, or friend is miles away.

- Data on children missing from foster care shows that although there was an initial decrease in the number of children running away from foster care under the current grants (October 2019), the number of children running from foster care has increased from a low of 55 in January 2020 to a range of 60 to 77 in the months since.

- There has been a slight increase in the number of children recovered each month since October 2019. However, it can vary significantly given the fluid nature of runaway children and data on them. For example, the range of children recovered each month ranged from 31 to almost 70.

- We were unable to compare the current effectiveness of DCF’s Special Response Team policies to their previous efforts because we did not have reliable data on runaway children prior to the current grants. We found the runaway data kept in FACTS prior to the current grants to be incomplete and unreliable.

Causes of Safety-Related Problems

High caseloads and data use likely caused many of the issues we found related to child placement and safety.

- Many case management staff say high caseloads make it difficult to comply with DCF policies on child safety. In our survey of all 600 foster care case management staff in the state, 228 case management staff responded for a response rate of 38%. Close to 20% of those case management staff respondents indicated that their caseloads made it difficult to assess and monitor the safety of children on their caseload.

- Respondents said that staffing shortages and burnout make caseloads even higher and affect the ability of case workers to carry out their duties. Case management staff made the following comments:

- “It is not possible to complete my duties with my level of training, case load, and available resources.”

- “We are highly overworked, understaffed, underpaid and too many demands on how things need to be completed with a short amount of time to get things done in. With staff leaving, this puts more work on top of the work that we already have to get in on deadline.”

- Case management staff also told us when their caseload is high, urgent or emergency incidents in one case might result in them missing visits or other services for others on their caseload. When a critical incident or emergency occurs, their time and resources are directed to resolving that situation. For example, a survey respondent reported:

- “When one child is disrupting or struggling, it causes great disruption in providing services for other families and can delay progress made in their cases.”

- More detailed analysis of caseload levels in the state and the impact it has on the state’s ability to provide foster care services can be found in Question 2.

- Further, not using comprehensive and existing data makes it difficult for DCF and case management staff to make informed placement decisions, track issues when they arise, and generally measure performance in key safety areas.

- Case management provider officials told us CareMatch, as the current comprehensive data solution, does not have robust enough information for case management staff to make placements for children in foster care.

- Case management provider officials told us they are tracking their customer communication complaints. DCF is also tracking the ones they receive directly. Still, DCF currently does not have a comprehensive, uniform way of tracking complaints across the whole system. This limits their ability to identify systemic or regional staff performance issues. It also, makes it difficult to determine if case management staff are properly resolving issues that might affect a child in foster care. Or, to even have assurance that all incidents of safety concerns are reported to case management staff and DCF.

- Currently, one of DCF’s main tools for identifying systemic and performance issues is quarterly file review. The sampling for these reviews is only a small portion of the overall cases in the state. Comprehensive data would allow for more targeted performance and program management improvements.

DCF has not taken action to correct systemwide safety issues despite continued concerns about the safety of children in foster care.

- Issues related to child safety and well-being are not new. Figure 3 shows that DCF is aware of many of these same issues.

- Comprehensive data will improve data quality and provide DCF better information to make systemwide and management decisions. However, DCF does have much of this data already. The comprehensive system will only help improve the safety of children in foster care if DCF uses it to take corrective actions.

- In the past, DCF has used its discretion with its case management providers.

- Case management staff told us until recently DCF staff usually discussed unmet outcomes with them but did not necessarily issue formal corrective action.

- DCF officials told us that when the current grants started in October 2019, there was a grace period with case management providers before they expected outcomes to be met. However, DCF is now putting providers on PIPs. DCF started formal PIPs in the fall of 2021 with each case management provider. The review of these PIPs will continue quarterly through the end of fiscal year 2022. DCF officials told us at that time they will assess and consider penalties for any outcomes case management providers have not met.

- Not taking formal corrective action when key safety and well-being outcomes for children in care aren’t met doesn’t prioritize child safety. Further, it creates the risk for potential unsafe practices to continue.

- The 2018 class action lawsuit settlement and recent state efforts for independent oversight of the foster care system are designed to provide additional accountability in the system. For example, the settlement requires DCF and case management providers meet certain outcomes in areas like placement stability. It also provides for additional oversight by mandating an independent advisory group. However, it is too early to tell what effect these measures will have.

The state does not have the capacity to provide services to all children in foster care, especially those with specialized service needs.

Foster Home Capacity

Federal and state benchmarks require case management providers place children close to their home communities and in homes with sufficient capacity.

- Federal and state outcome measures require DCF and its case management providers to try to place children in the same community and school they were in prior to entering foster care. This is so a child can maintain connections to their communities and visit with their families as they work towards permanency. DCF has a policy that defines an appropriate placement as being one near the child’s relatives and current school.

- To have placements that keep children in their communities, each community needs enough capacity for the placement needs in their individual community.

- Further, best practices suggest DCF should establish capacity limits so that foster homes don’t become overcrowded. That’s because overcrowding can increase the risk for negative outcomes like maltreatment.

- DCF has several policies outlining foster home capacity limits. Individual foster homes are licensed for a certain number of children. For example, no more than 4 children in foster care and a total of 6 children under 16 can be placed in a single home. Additionally, no more than two children under 18 months can live in the same foster home. Other factors like the number of bedrooms or a need for specialized training can also affect a foster home’s capacity limit.

- DCF allows homes to be over capacity as an exception, but those homes must have approval from DCF. DCF approves temporary capacity exceptions when it’s in the best interest of the child and does not violate statutory requirements regarding who a child can be placed with (e.g., the foster parent still must have passed all background checks). For example, this exception might happen when children are part of a sibling group or in cases of an emergency placement.

Most Kansas counties had enough foster home capacity to meet their demand in fiscal year 2021, but close to 40% of the state’s counties might not have enough foster home capacity.

- To determine if the state has enough foster home placements to keep children in their communities, we estimated how many foster home placements each county needs. We compared the licensed capacity of foster homes in each county to the number of children removed from that county in fiscal year 2021. We adjusted for types of placement children entering and exiting foster care are in (e.g., a child in an unlicensed relative placement doesn’t need a licensed foster care bed).

- The state appeared to have enough homes and capacity in fiscal year 2021, but those homes were not necessarily in the communities where they were needed. Overall, the state was using about 50% of its licensed capacity. The state had about 2,700 licensed foster homes with the capacity for about 7,000 children. The state had about 7,000 children in foster care, but only half of them were placed in foster homes. The other half of children in foster care were mostly placed with non-licensed relatives and kin or in facility placements.

- However, on a county basis 39 counties were at, above, or close to capacity. Figure 5 shows the number of licensed beds available in each county in the state. As the figure shows:

- 19 counties are overcapacity and have no additional beds for children entering foster care in those counties. They are shown in red in Figure 5. For example, Elk county would need an additional 8 beds to place the children in the same county as their home. Mitchell county would need an additional 7 licensed foster care beds. Pratt would need an additional 13 licensed beds. Wyandotte would need an additional 23 licensed beds.

- Another 5 counties are at full capacity, meaning they have no more available beds should more children in their county need them. These counties are shown in Figure 5. They include Barber, Greeley, Harper, Lyon, and Ness counties.

- Another 15 counties are close to capacity (3 or fewer available beds). These counties are shown in Figure 5. If a sibling group needed placement in these counties, it is unlikely that the children could be kept together in their home communities.

- We estimate some counties have significantly more available foster homes than the number of children entering care in those counties. For example, Labette has about 100 more beds available than children entering foster care. Johnson county has about 480 more beds than needed. Butler has about 140 more than needed. Douglas has about 75 more than needed. Crawford has about 110 more. Sedgwick county has about 1,125 more beds than needed.

- These results are similar to findings from our previous audits of the foster care system. In our 2017 audit, we found more than 40 counties in the state may not have had enough foster homes.

- When an area of the state doesn’t have the capacity to place a child, the child may have to be moved away from their home. That makes it difficult to maintain community and familial connections and potentially delays permanency, all of which is harmful to the child’s well-being. It could also mean that a child is placed in a home that is overcapacity, increasing the risk of maltreatment or neglect.

Even when counties have enough licensed foster homes, stakeholders told us the state may not have enough homes to care for children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs.

- According to best practices, children with complex or extreme physical, emotional, or behavioral needs should only be placed with the most experienced and well-trained foster parents. Examples of the types of needs that may require more experienced placements include children with down syndrome, bi-polar disorder, muscular dystrophy, those who have committed juvenile offenses, those with substance abuse histories, and those with sexual behaviors. CPAs sponsor foster parents to get the training and licensing needed to successfully care for these children.

- It’s unclear how many foster homes in the state can take children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs, because that information is not uniformly tracked across licensing data and CPAs. The information may be available to case management providers in CareMatch if CPAs provide it. This also means information on foster homes that can take children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs may not be available to case management providers when they are making placement decisions. Instead, case management provider officials said they make case-by-case decisions on placements that can meet a particular child’s needs using their own knowledge and systems.

- We spoke to stakeholders with the Kansas Foster and Adopt Parent Association, Kansas Appleseed, Children’s Alliance, and the Kansas Chapter of the National Association of Social Workers to understand how Kansas’s foster care system ensures needs are met in foster homes. Stakeholders told us that although the state might have enough foster homes in general, they do not have homes that can provide for specific needs, including specialized needs.

- Additionally, 6 of the 228 case workers who responded to our survey also told us in their comments that the state lacks foster homes willing and able to take youth with significant behavioral or mental health needs. They mentioned the difficulty of finding homes specifically for children who have experienced trauma or committed a juvenile offense. For example, comments included:

- “The type of behaviors children are having have escalated, making long term placements difficult to locate for them. Children who would have previously been placed in detention or JJA [Juvenile Justice Authority] custody OOH [out-of-home] are now entering the CINC world and placements are not prepared with training on these escalated behaviors and how to deal with children who destroy property, cause physical harm to others, use illegal substances, etc.”

- “There is also a significant lack of foster homes, especially homes that are willing to be patient and supportive for youth with significant behaviors due to trauma, which results in youth being in the office or without placement.”

- Not having enough homes trained to take children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs can result in serious injury to the child. It can also lead to placement instability, and the well-being of the child suffers. In our survey of licensed foster parents in the state, several commented on situations where a child with needs higher than they were able to care for was placed with them, leading to a stressful experience for the foster parents and instability for the child.

- Further, case management officials told us foster parents trained to take children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs also need trained support services (e.g., schools and community mental health centers) available to them in their communities. A foster parent may be trained and experienced with children with complex needs, but without support services available for those needs, it is difficult for the child to be successful. We discuss more about the availability of services later in the report.

DCF told us they are looking into options to address placements for children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs.

- DCF currently has active efforts in partnership with case management providers and CPAs to try to recruit diverse foster homes across the state. They also reported that they are updating the required license training to include diverse needs and background training. They have family first and kinship initiatives that prioritize keeping children with family, which also reduces the need for licensed foster home placements and keeps children in familiar settings.

- Other states use the therapeutic or treatment foster care (TFC) approach to provide homes and services to children with high physical, mental, or behavioral needs. TFC allows children with specialized needs to be in a family-like setting and be served in the community (as opposed to a facility placement). The foster parents in a TFC setting are highly trained to care for a child in foster care who might otherwise be placed in a treatment facility. States like Missouri, Illinois, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Tennessee have TFC programs.

- DCF officials said they currently don’t have a TFC option. However, they are in the process of researching TFC and other professional foster home models. Not having therapeutic foster care homes puts more stress on foster parents, who might not have training to care for the highest needs cases. Currently, those children are likely to end up in a state psychiatric facility. Those facilities currently have waitlists. Therapeutic foster homes offer another option for children in need of facility placement. It also increases stability of placement for those children, who are more likely to frequently move from placement to placement when traditional foster homes are unable to meet their needs.

- DCF reported to us several other efforts they have made to address placements for children with complex needs. They include:

- Increased crisis supports with the Family Crisis Response and Support contract of all individuals under the age of 20 in the state. This is a centralized crisis helpline with mobile response support services aimed to meet needs in an immediate crisis and prevent institutional treatment.

- Increased the licensed bed capacity for Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTF) in the state over the past year to about 425. Although, as we will discuss, these beds still need staff available.

- Amended KDADS contracts with Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) to ensure a child’s mental health service is not interrupted if the child moves placement. The amendments also assure new children with mental health needs are promptly seen. They do this by requiring a dedicated foster care referral phoneline and email address. All referrals made to the CMHC through the line must be responded to within 72 hours for scheduling intakes and assessments. We did not confirm these amendment details.

Caseload Capacity

Caseloads for case workers were higher across the state than best practices recommend.

- Case management staff provide many of the services children in foster care need to achieve permanency. It is important staff have reasonable caseloads so they can provide each child the quality of services and individual attention they need.

- DCF and the case management providers may use a team of people to provide for children. A licensed or otherwise appropriately trained case manager is paired with an unlicensed family support worker for some cases. When paired, the case manager and family support worker evenly divide the workload for the case. When reporting their caseloads to DCF, case management staff report caseloads per case manager. For that reason, it is possible in some instances that the numbers reported here represent case managers with family support workers assigned to their cases to help with the workload.

- DCF’s policies did not meet best practices. Best practices varied, but generally were between 12 to 18 children in foster care per case worker. DCF grants allow for 25-30 children in foster care per case manager, significantly higher than best practices.

- DCF officials said they consider 25 to 30 cases the maximum. They based it on experience in the field, the Council on Accreditation (COA), Child Welfare League of America (CWLA), and Annie E. Casey Family Programs research. DCF officials told us the COA and CWLA guidance is to keep caseloads low and manageable, but they do not set specific numbers.

- However, in our research we found that the COA has set numbers between 12 and 15 children per worker. Further, other states such as Texas and South Carolina have recently instituted standards between 12 and 18 children per worker as well.

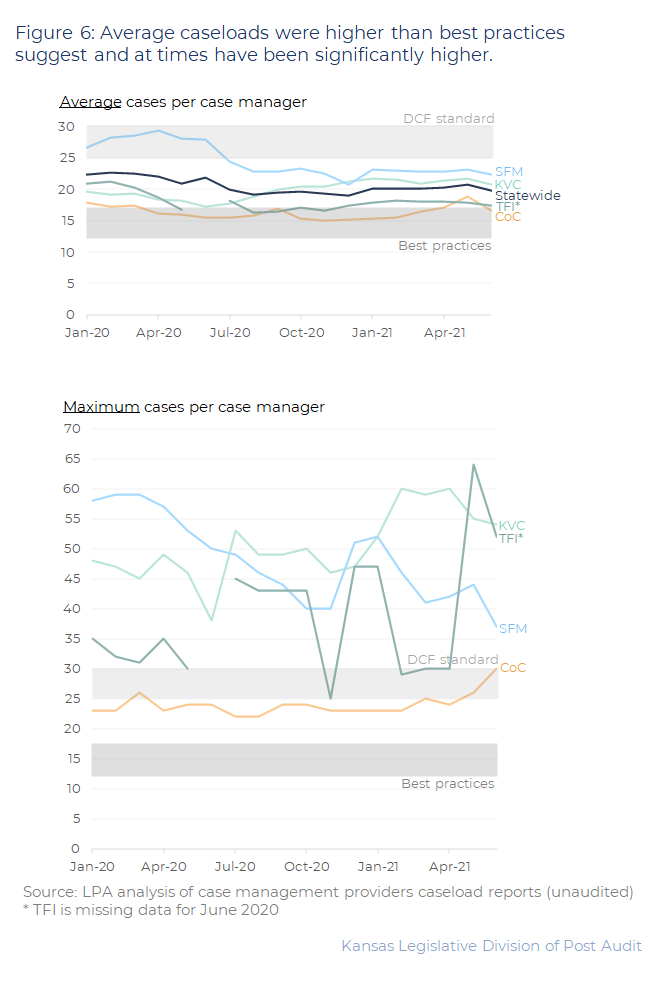

- We looked at caseloads from January 2020 to June 2021. Case management providers report caseloads each month to DCF. Figure 6 shows the average and maximum number of cases for each case manager by provider. As the figure shows:

- Case management providers’ average caseloads were generally higher than best practices but lower than DCF’s standards. Case management providers’ average caseloads varied from month to month and by provider. They were between 16 to 24 cases per case manager. However, their maximum caseloads reached as high as 64 cases per case manager during this time.

- Case management officials told us caseloads vary significantly based on vacancies from month to month. At times case management providers can temporarily have other offices help cover vacancies, but that is not always an option. Training time and the number of cases new staff can initially carry can also impact monthly caseloads.

- Although the state averages are under DCF standards, there are still instances where case management providers are carrying more than the DCF standard. Each month, between 26 to 45 case managers had more than 30 cases. The number of workers carrying more than 30 cases has generally been increasing since the fall of 2020. KVC and St. Francis Ministries have the most staff carrying more than 30 cases per case manager. KVC and St. Francis Ministries officials told us they use case managers paired with a family support worker for their cases. So, these instances include both a case manager with family support workers.

- Case management provider officials told us that caseloads get higher than they should because of staff shortages and turnover. They told us this is occurring because of low pay, long hours, and general burnout among case worker staff. They said COVID has made these staffing issues even worse. When a worker leaves, their cases must be reassigned. When a new worker is hired, they are not able to take cases immediately while they are training. Finally, case management officials told us that they don’t automatically reassign cases when a worker has a high caseload. That’s because they want to ensure continuity of care for the children and families on a worker’s caseload whenever possible.

- These are similar to findings from our 2017 audit and indicates caseloads have continued to increase since then. In that audit, we reviewed caseloads for fiscal years 2014-2016. We found that case managers averaged less than 30 cases per month, but frequently held maximum caseloads that exceeded 30 cases during that time. For example, 6 to 20 case managers held more than 30 cases in each month of the 3-year period we reviewed in 2017.

Case workers we surveyed told us high caseloads made it difficult for them to do their job.

- In our survey of all 600 case management foster care workers in the state, we asked workers if they can manage their current caseload in a typical 40-hour work week. Our response rate was 38%.

- The majority of survey respondents (84%) said they were not able to manage their caseload in a typical 40-hour work week. Most respondents (61%) said they needed to work an additional 3 – 10 hours a week to manage their caseloads. The other large share of respondents (33%) reported needing to work 11 – 20 additional hours a week to manage their caseloads.

- Survey comments indicate case workers struggle to perform their job duties with their current caseloads. For example, comments include:

- “Although I am salary for 40 hours/week, I typically work 50 to ensure my work is completed. Even when I work overtime, it seems as though I cannot accomplish everything that needs done.”

- “I regularly work close to 20 hours overtime weekly and still am behind and am told I need to be doing more to meet the needs of my case load.”

- “The case loads are too high to manage all the paperwork, visits, and transportation needed to properly care for the children and families we serve.”

- “I feel as though our heavy caseloads come at the expense of all of our clients. We are taught to be client-focused, however, our workloads don’t afford us ample opportunity to connect with our clients and spend the time to ensure their needs are being met.”

- Unmanageable caseloads mean workers are not able to spend enough time with the children and families on their caseloads, hindering their ability to develop appropriate case plans, monitor child safety, ensure services and supports are in place, and achieve a positive outcome on a case. Further, unmanageable caseloads contribute to high worker turnover.

- To reduce caseloads, the system needs more case workers, and they need the case workers to stay. To try to address recruitment and retention, DCF and case management officials told us they introduced pay raises for support positions, instituted self-care practices in their offices (e.g., optional morning meditation meetings), paid practicums, flexible work schedules, and are working with local universities to continue training partnerships and revive previous federal social work training programs. However, it remains to be seen if these efforts are enough to recruit new case workers, retain current case workers, and ultimately lower caseloads.

Mental, Behavioral, and Specialized Services

Case management staff are responsible for coordinating physical, mental, and behavioral health services for children.

- DCF policy charges case management staff with assessing, planning, implementing, coordinating, monitoring, and evaluating all services for a child. Policy specifically states that services should be individualized, culturally responsive, and link children and families to community-based services. DCF and case management providers officials told us they coordinate with state and local agencies that provide services (e.g., KDADS, Community Mental Health Services, and schools) to find services for children.

- DCF provides case management staff with an initial assessment showing which services a child may need. Case management staff should coordinate additional screenings as needed within 20 days of entry into foster care. Any services or needs identified must be provided to the child while in foster care. The case management staff must coordinate with community health providers, private practitioners, birth families, and foster families to ensure the child receives needed services. Case management staff should reassess the child when the child experiences a significant change in their situation. Figure 2 shows where the state’s community health providers are located.

- Children in foster care are enrolled in Medicaid. The Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services (KDADS) administers the state’s Medicaid waiver programs for disability and mental health services. They also operate the state’s hospitals and institutions. Therefore, case management staff may also need to coordinate with KDADS.

- Once case management staff have identified services for the child, they make referrals to providers and the child’s foster family is responsible for scheduling and transporting the child to services. Case management staff told us they document any services in a child’s case plan and in court reports. All that documentation should be maintained in the child’s case file.

Across the state, children may not have always received services they needed, especially specialized or acute services.

- We wanted to look at whether children in foster care received the services they needed and in a timely manner at a statewide level. We could not perform this analysis because case management providers and DCF officials were not aware of any aggregate, statewide tracking of what services children need and which ones they are receiving. Instead, case management staff track this information in various places within individual files (monthly reports, case logs, etc.).

- Instead, we looked at DCF quarterly file review results. Ensuring that children are receiving services they need while in care is part of federal performance standards. DCF tracks this in their quarterly file review. Using questions based on federal outcomes, DCF staff experienced in child welfare read a sample of files and look for evidence that a child’s physical, dental, mental health, and educational needs were assessed, and that case management staff provided services for all identified needs. They look at documentation of required assessments and evidence of required appointments occurring. We did not audit DCF’s file review and process, and we cannot confirm the reliability or accuracy of their results.

- In their latest quarterly review of case files (July 2021 through September 2021) DCF found that children didn’t always receive services to meet their needs. DCF reviewed 169 files and found:

- 61 (36%) cases where the child did not have appropriate physical health services provided.

- 73 cases (43%) where the child did not have appropriate dental health services provided.

- 26 cases (15%) where the child did not have appropriate mental/behavior health services provided.

- 16 cases (10%) where the child did not have appropriate education services provided.

- We also asked foster parents and case management staff about their experiences in getting services for the children in their care. We surveyed 600 foster care staff for their opinions on how easily they can access services and how quickly children got the services they needed. 228 responded to our survey (38%). We also surveyed 2,600 foster parents and 959 (37%) responded.

- Some foster parents reported difficulties and delays over getting children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs the specialized services they required. Specialized services refer to unique treatments an individual needs due to a serious mental, physical, or behavioral health condition. Most foster parents who responded to questions about services reported being able to receive mental/behavioral services (85%), medical services (97%), or specialized services (83%) as the child’s case plan required. However, 15 to 17% reported not being able to get mental/behavioral or specialized services as frequently as the child’s case plan required. Also, most foster parent respondents reported it taking a month or longer to get their first mental/behavioral or specialized service appointment for children in their care.

- Comments we received indicate delays and access barriers too, including:

- “Access to psychiatric help and specialized services is very difficult in our area, especially in the summer.”

- “The hardest thing I have had trouble getting has been the universal packet required for me to set up mental health services. The doctors appts I can set up on my own. I cannot just walk into the mental health center and start services. I have had cases where it took over 6 months to get the packet.”

- “Mental health needs to be an easier access to obtain for these kids. Insurance should not kick a kid out of a facility because they do not think there is an issue.”

- A significant number of case management staff also commented on the difficulty getting specialized services for children with complex physical, emotional, and behavioral needs children:

- The majority (75%) of case management staff respondents said psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTF) were difficult to access. These facilities provide out-of-home psychiatric treatment to children with serious mental or behavioral health needs. DCF staff told us children are often in unstable placements while waiting for a PRTF bed. The state currently has 9 PRTFs. The majority of (54%) case management staff respondents reported that it took longer than 1 month to access PRTF.

- 63% of case management respondents said they do not have access to an acute hospitalization bed within a day for a child on their caseload. Acute hospitalization refers to short-term hospitalization for a severe condition. This can include psychiatric conditions. Federal requirements state that acute hospitalizations should occur immediately upon evaluation of the child and bed availability. Even though federal requirements allow for delays due to bed availability, the state does not have the capacity to meet the needs of those who need immediate hospitalization.

- Approximately 40% of case management respondents said that services for autism treatment, serious emotional disturbances (SED) waiver, Intellectual/Developmental Disability (I/DD) supports, or other specialized behavioral health treatment services were difficult or very difficult to find. Further, getting those specialized services took more than a month or weren’t available at all according to 40 to 50% of respondents.