Reviewing Issues Related to State Cryptocurrency Tax Policies

Introduction

Senator Robert Olson requested this limited-scope audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its February 16, 2022 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following question:

- How do Kansas’s cryptocurrency tax policies compare to federal policies and best practices?

To answer the audit question, we reviewed and summarized recent cryptocurrency policy documents from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and the Kansas Department of Revenue to determine what policies exist on cryptocurrency taxation. We also reviewed relevant publications from the Uniform Law Commission, the U.S. Treasury, and the National Conference of State Legislatures to provide more context to the audit findings. We also interviewed officials from the Kansas Department of Revenue to understand how the state taxes cryptocurrency and how Kansas’s tax code interacts with the federal tax code. We attempted to review best practices on cryptocurrency taxation. However, we were unable to find any best practices at this time. More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

We focused on federal and Kansas policies related to the taxation of cryptocurrencies. Cryptocurrencies are just one type of crypto asset that use blockchain technology. We did not consider laws or regulations dealing with other crypto assets like security, utility, or non-fungible tokens. We briefly looked at cryptocurrency tax legislation in other states to identify general themes; however, we did not study this legislation in detail.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Kansas’s cryptocurrency tax policies generally aligned with federal policies, but some of those policies have been difficult to enforce in recent years.

The number of cryptocurrencies increased in recent years, but their use is still relatively uncommon.

- A cryptocurrency (also known as a digital or virtual currency) is a digital representation of value that can be used to buy property, goods, or services, or held and traded as a speculative investment similar to stocks, bonds, or foreign currency.

- Cryptocurrencies use complex encryption to secure transactions that are recorded on a public blockchain that is maintained by a network of users who validate transactions. A blockchain is a digital ledger that tracks the movement of cryptocurrency from one owner and another. Exact copies of the ledger are kept by each member of the blockchain network to help ensure accuracy of these transactions. The following example demonstrates the transfer of one bitcoin. Although this example is for bitcoin, could also apply to other cryptocurrencies.

- Individuals use a private key to access any bitcoin they acquire. For example, say Person ‘A’ buys one bitcoin from Person ‘B’ on March 1st, 2022. This purchase could be made with whatever Person ‘B’ agrees to sell their bitcoin for (ex. U.S. dollars, another currency or cryptocurrency, or other property, goods, or services). If the transaction is approved by the blockchain network, an entry will be added to the blockchain for that time and Person ‘A’ will receive a private key. Similar to a banking PIN, individuals use their private key to access their bitcoin.

- Private keys are typically held in digital wallets which are special hardware (i.e., flash drives), or software designed to hold and transfer the keys. For example, digital wallets have a public address—called a public key—that is used when receiving cryptocurrency. In this way the key is similar to a bank account number. Wallets can be custodial or non-custodial. Custodial wallets are hosted by third-party vendors, like a cryptocurrency exchange. These exchanges help users buy, sell, and transfer cryptocurrency. Conversely, non-custodial wallets are controlled by their owners without a third-party intermediary.

- Bitcoin transactions must first be approved or declined through the blockchain network. For example, say Person ‘A’ wants to buy something (e.g., good, services, property, etc.) from Person ‘C’ with their one bitcoin on March 30th, 2022. Person ‘A’ will use their wallet and private key to initiate a transaction with Person ‘C’s wallet address. The transaction will be approved by the blockchain network because the ledger will show the original purchase of the bitcoin by Person ‘A’ on March 1st. After the transaction is approved, Person ‘C’ will receive a private key for their new bitcoin, and there will then be a second ledger entry reflecting the transfer. If Person ‘A’ later tries to use the same private key to make a purchase, the transaction will be declined because the ledger will show that Person ‘A’ used that private key to transfer the bitcoin to Person ‘C’ on March 30th.

- A cryptocurrency can be acquired in a few different ways: in the example above, Person ’A’ could have purchased their bitcoin from Person ‘B’ either directly or through a cryptocurrency exchange (like stocks and bonds). Person ‘C’ then received the bitcoin from Person ‘A’ as payment for property, goods, or services. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies can also be acquired through participation in cryptocurrency specific activities like mining, staking, hard forks, or air drops. These terms are defined in the glossary in Appendix B.

- The number of cryptocurrencies has increased dramatically in recent years, but their use is still uncommon. Although Bitcoin and Ethereum are more commonly known, the IRS estimates that there are roughly 8,600 cryptocurrencies worth about $2 trillion dollars in total. However, a recent Pew Research Center survey of Americans on cryptocurrency use and knowledge found that only about 16% of American adults, about 40 million people nationwide, have used cryptocurrencies.

- Recently, some large retailers started accepting cryptocurrency as a form of payment. Unlike the U.S. Dollar, neither the Federal government nor Kansas considers any cryptocurrency to be legal tender. This is important because it impacts how cryptocurrency transactions are treated for tax purposes.

Federal tax policy is set up to tax cryptocurrency in several ways.

- The IRS taxes cryptocurrencies as property, and the use of cryptocurrency to buy property, goods, or services are considered taxable transactions. Federal policy taxes these transactions in two different ways:

- Individuals or companies that accept cryptocurrency as payment for goods, services, or property should report it as federally taxable income. For example, if a person accepts one bitcoin as payment for a $40,000 vehicle, they must determine the fair market value in U.S. Dollars of the cryptocurrency at the time of transaction. Fair market value is defined in Appendix B. That value should then be reported as part of an individual’s federal adjusted gross income (AGI) or corporate federal taxable income (FTI). Federal tax policies use AGI and FTI to determine an individual or company’s annual income tax liability.

- Individuals or companies who use cryptocurrency to purchase property, goods, or services may also be subject to federal taxes. Because cryptocurrency is not legal tender, purchases are treated as a trade of property. As such, the buyer could be subject to capital gains taxes. For example, in the situation above, if someone buys a $40,000 car with one Bitcoin that they originally acquired for $10,000, they realize a $30,000 taxable capital gain. That’s because the value of the purchase exceeds the original cost of the Bitcoin. That $30,000 dollars should be reported as part of the buyer’s AGI or FTI.

- Employee wages paid in cryptocurrency are subject to federal income and payroll tax withholdings. Additionally, cryptocurrency income from mining, hard forks, or airdrops should be reported to the IRS and may be subject to income and self-employment taxes where applicable.

- Speculative trading of cryptocurrency is subject to federal capital gains tax and should be reported in a taxpayers AGI or FTI. This is similar to how trades of stocks, bonds, or real estate are taxed. In recent years, the values of cryptocurrencies have fluctuated dramatically resulting in potentially large gains for cryptocurrency traders. For example, a person who bought one Bitcoin for about $6,000 in March 2020 could have sold it a year later for about $60,000: an 800% gain. People are required to pay capital gains taxes on such income, but this has been hindered by a lack of reporting requirement from cryptocurrency exchanges. This is discussed more below.

Kansas’s income tax code mirrors federal tax policy, thus the state should receive tax revenue from cryptocurrency transactions.

- Many states, including Kansas, choose to adopt federal tax policies as the basis for their tax code. This is commonly referred to as tax code conformity. States do this to simplify their tax codes, reduce complications for taxpayers, and reduce the state audit and enforcement burden. Since the 1970s, the Kansas income tax code has used the federal AGI (K.S.A 79-32,117(a)) and FTI (K.S.A. 79-32,138(a)) as starting points to calculate state income taxes.

- Because Kansas uses AGI and FTI as its starting point for state income taxes, Kansas should receive tax revenue from reported cryptocurrency income earned through the transactions we described above (accepting cryptocurrency as payment, trading cryptocurrency, etc.). Basically, federal and Kansas income taxes policies are the same, and if someone reports income to the federal government, it will be reported to Kansas too.

- It is not clear how much income tax revenue the state has collected from cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency income is aggregated with other sources of income at the federal level, and the Kansas Department of Revenue (KDOR) does not receive detailed data which would allow them to identify individual income sources. KDOR did report that about 20,000 Kansas tax returns—out of 1.5 million (1%)—likely had cryptocurrency transactions in 2021. This estimate was based on a ‘Yes or No’ question about cryptocurrency transactions the IRS added to the federal individual tax return in 2020. As will be discussed below, this is likely an underestimate due to underreporting of cryptocurrency income.

- KDOR also issued notices clarifying how state sales tax should apply to cryptocurrency transactions. Issued in 2020, KDOR Notice 20-04 requires retailers and service providers that accept cryptocurrency to calculate and remit sales taxes in U.S. Dollars. This should be based on the fair market value of the property, goods, or services sold. KDOR does not consider cryptocurrency to be legal tender and does not accept cryptocurrency for any payment or remittance.

It’s unlikely Kansas receives all income tax revenue from cryptocurrency transactions because of a lack of federal reporting guidelines.

- Although cryptocurrency transactions should be taxed under federal policy, a lack of third-party reporting has made it difficult for the IRS to enforce those polices. A recent U.S. Treasury audit found that it has been difficult for the IRS to identify taxpayers with cryptocurrency income. As highlighted above, it is ultimately the responsibility of the individual or company to report cryptocurrency income to the IRS. However, only about 45% of taxpayers accurately report their income in cases where there is little or no third-party reporting. Examples of third-party reporting include, employer reporting of employee wages, and bank reporting of account holder interest income.

- Because of the lack of federal reporting, it’s unlikely Kansas receives the full amount of tax revenue from recent cryptocurrency transactions. As mentioned above, KDOR uses the federal FTI and AGI as its starting point for the state’s income tax. It appears that some individuals have not consistently reported cryptocurrency income on their FTI or AGI, mostly due to a lack of third-party reporting. If individuals don’t report their cryptocurrency income to the IRS, that income will also not be reported to KDOR. As a result, the state would not receive tax revenue from any unreported cryptocurrency income.

- A recent U.S. Treasury audit determined that the IRS needs better third-party reporting standards for cryptocurrency transactions to improve compliance. They highlighted third-party cryptocurrency exchanges as a good source of information because they play an important role in facilitating cryptocurrency transactions. This includes the buying and selling of cryptocurrencies and the processing of cryptocurrency payments made to merchants. Recent estimates cited by the Rand Corporation suggest that over 90% of cryptocurrency transactions are done through exchanges.

- The 2021 Federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act should improve third-party reporting of cryptocurrency transactions in coming years. The Act mandates that exchanges annually report customer information and transactions to customers and the IRS starting in 2023. However, third-party reporting by cryptocurrency exchanges will likely not solve all issues of noncompliance. There is still uncertainty about what can be done to identify transactions done with non-custodial wallets. Cryptocurrencies are designed to be used without third-party intermediaries. Although third-party exchanges provide convenience in cryptocurrency transactions and private key storage (custodial wallets), they are not required, and increased regulation could cause some users to conduct their transactions outside of an exchange.

State governments have yet to agree on a set of best practices regarding the taxation of cryptocurrencies.

- Interstate organizations like the Uniform Law Commission and the Government Finance Officers’ Association have issued guidance for states on the regulation of cryptocurrency, but taxation is not specifically addressed.

- As part of this audit, we spoke to an official with the National Conference of State Legislatures who tracks state cryptocurrency legislation. The official explained that a major hurdle to the creation of best practices has been the complexity and instability of the cryptocurrency industry. New crypto products are constantly being developed, and state lawmakers and regulators are still trying to determine how cryptocurrencies fit within their legal frameworks.

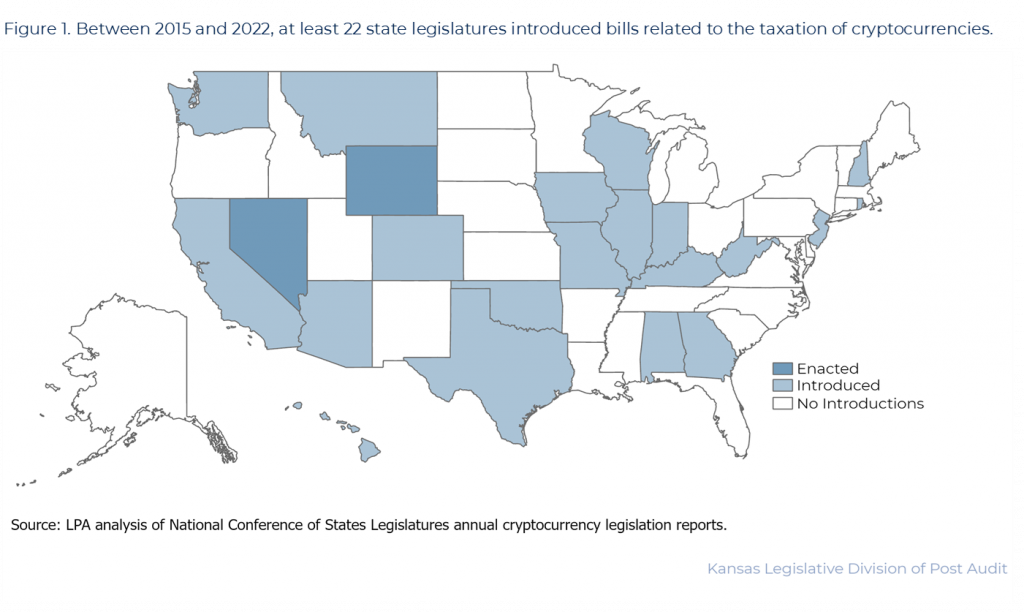

- Figure 1 shows states that have introduced legislation related to cryptocurrency taxation. At least 43 bills have been introduced in 22 states related to cryptocurrency taxation since 2015. However, only two bills have been enacted as of March 2022. These bills included proposals to tax cryptocurrency transactions, regulate the use of cryptocurrencies to pay for government taxes and fees, and bills to incentivize cryptocurrency processing (e.g., miners) activity in their states.

Recommendations

We did not have any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On May 23, 2022 we provided the draft audit report to the Kansas Department of Revenue. Agency officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- 16% of Americans say they have ever invested in, traded or used cryptocurrency. (November 2021). Pew Research Center.

- Kansas Department of Revenue Notice 2014-21. (2014). U.S. Internal Revenue Service

- Kansas Department of Revenue Notice 2019-24 (2019). U.S. Internal Revenue Service

- The Internal Revenue Service Can Improve Taxpayer Compliance for Virtual Currency Transactions. (September 2020). U.S. Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration.

- Understanding the Heated Debate Over Cryptocurrencies and Tax Compliance. (August 2021). The Tax Policy Center.

- The Taxation of Cryptocurrency: Virtual Transactions Bring Real-Like Tax Implications (January 2019). The CPA Journal.

- Notice 20-04: Sales Tax Requirements Concerning Digital Currency Under the Retailers’ Sales and Compensating Tax Acts. (November 2020). Kansas Department of Revenue.

- Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform. (January 2019). The Tax Foundation.

- Cryptocurrency 2014-2016 Legislation. (July 2018). National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Cryptocurrency 2017 Legislation. (July 2018). National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Cryptocurrency 2018 Legislation. (December 2018). National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Cryptocurrency 2019 Legislation. (December 2019). National Conference of State Legislatures.

- Cryptocurrency 2020 Legislation. (December 2020). National Conference of State Legislatures.

Appendix B – Glossary of Cryptocurrency Terms

- Air Drop: An airdrop is a means of distributing cryptocurrency to the wallet addresses on a cryptocurrency’s ledger. An air drop may be done to distribute new coins after a hard fork of an existing cryptocurrency or as part of a scheme to promote the use of a new coin that has no predecessor.

- Blockchain: Blockchain is one type of distributed ledger that arranges the data in blocks that are connected sequentially. This unique way of structuring data gives blockchain transactions additional security as they are irreversible. Blockchains can be used to store many types of data but have recently become popular for their use of storing cryptocurrency transaction history.

- Crypto Assets: Crypto assets are digital assets that use complex encryption, peer-to-peer networks, and a distributed ledger technology– such as blockchain – to create, verify and secure transactions and prove ownership. In addition to cryptocurrencies, common crypto assets also include,

- Utility Tokens: Tokens used on an issuer’s network to purchase specific products of services, similar to store credit.

- Security Tokens: Like stocks, security tokens are sold to investors to help the issuer raise money. They often confer partial ownership rights like voting and profit-sharing.

- Non-fungible Tokens (NFTs). An NFT records ownership of a unique tangible or intangible object like a song, digital image, video, etc.

- Distributed Ledger: A distributed ledger is a type of decentralized database that stores electronic records that are shared and maintained by members of the decentralized network. Each new transaction must be agreed upon by all members of the network before it is added to the ledger better ensuring accuracy.

- Fair market value: The price at which property would change hands between willing and knowledgeable buyers and sellers. The fair market value of a cryptocurrency is generally its exchange rate in U.S. dollars at the time of the transaction; however, in cases where an established exchange rate does not exist, fair market value in a transaction would be equal to the fair market value of the property, goods, or services exchanged for the cryptocurrency at the time of the exchange.

- Hard Fork: A hard fork occurs when a cryptocurrency on a distributed ledger undergoes a protocol change that results in a permanent diversion from the existing distributed ledger and the creation of a new cryptocurrency on a new distributed ledger. This can lead to the airdrop of units of the new cryptocurrency to the users of the legacy cryptocurrency. For example, in August 2017 a disagreement between bitcoin users led to a hard fork divided bitcoin divided into two separate coins, Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash. Each holder of a bitcoin was entitled to one bitcoin cash coin after the split.

- Mining & Staking: Mining is the competitive process in which miners compete with one another to verify and add new transactions to the blockchain for a cryptocurrency. The miner that can complete the verification first is rewarded with some amount of the currency and/or transaction fees. Staking is like mining in that it serves to verify and add new transactions to a cryptocurrency’s blockchain. Participants can ‘stake’ their cryptocurrency holdings to guarantee the legitimacy of new transactions added to the blockchain in exchange for cryptocurrency payments and/or transaction fees. In the example provided above on page 3, these would be the people or companies processing the transactions on the blockchain ledger between Persons A, B, and C.