Trends in Social Workers Employed by School Districts

Introduction

Representative Landwehr requested this limited-scope audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its December 16, 2021 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following question:

- How has the number of social workers employed by school districts changed in recent years?

To answer the question, we analyzed employment data that school districts reported to KSDE from 2019 to 2021. We interviewed staff from 5 school districts in Kansas to understand any trends we saw in the districts and to discuss the social workers the districts employ (salary information, challenges hiring social workers, and the impact the Mental Health Intervention Team Program had on their decisions). We also interviewed stakeholders from 5 Community Mental Health Centers to understand the impact school districts’ hiring decisions have on the services they offer.

More details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report limitations on the reliability or validity of our evidence, and any work we did on internal controls and deficiencies we identified. In this audit, we performed limited reliability tests on the KSDE data. That work revealed issues with KSDE’s reporting guidance to school districts. It also revealed issues with the consistency of KSDE’s data. However, we think the data is reliable enough to draw the limited conclusions we have in this report. We included details on these issues and limitations later in the report.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

The number of licensed social workers employed by school districts in Kansas has increased over the last few years.

Background

School districts in Kansas employ licensed mental health care staff to provide several different services to students.

- School districts employ a few different types of mental health staff. For example, they employ social workers, psychologists, and counselors. School social workers provide services to students, teachers, or families to help address issues that affect students’ emotional well-being and academic performance. School counselors generally provide academic support like career development or goal-focused counseling to students. School psychologists provide more intensive mental health support like individual behavior assessments and counseling to students.

- School districts can hire licensed staff to fill a role that is different from their license. For example, school districts sometimes hire licensed social workers to work as counselors instead of doing social work.

- School districts have employed mental health care staff for a long time. In recent years, school districts have expressed a growing need for mental health services. Yet, they told us mental health care staff are difficult to hire because there is a widespread shortage of these staff.

The Kansas Legislature created the Mental Health Intervention Team program in school year 2019 to increase students’ access to mental health care resources.

- In Kansas, 26 community mental health centers (CMHC) provide services to all 105 counties in Kansas. As such, these CMHCs are the primary mental health resource for school districts. CMHCs are organizations charged with providing comprehensive mental health services like outpatient care, rehabilitation services, and other clinical support to Kansas communities.

- The program is intended to coordinate mental health care between school districts and the community to help address districts’ need for mental health care services for their students.

- The program created teams of mental health staff to serve participating school districts. These teams were placed inside the schools to identify students in need, communicate with the families of those students, and then to connect the students and families with community mental health resources. Overall, this strategy intended to improve students’ access to mental health care.

- Those teams include staff employed by school districts and staff employed by CMHCs. For example, the program created a school liaison position within school districts. The school liaison is a school district employee. The teams also include clinical therapists and case managers. Those staff are CMHC employees.

- School liaisons help identify students in need and communicate with the CMHC staff, the students, and the families to figure out how to best serve each student. School liaisons do not have to be licensed mental health staff, but they can be. For example, districts may hire an individual generally qualified in behavior intervention as a school liaison. But districts may also hire licensed social workers, psychologists, or counselors as school liaisons.

- Clinical therapists develop treatment plans and provide clinical care to students.

- Case managers help identify students in need, reach out and engage with students and their families, participate in treatment planning, and communicate with the liaisons, school staff, and families about student needs as necessary.

The Legislature has reauthorized and expanded the number of districts the program serves each school year since 2019.

- The program became effective in school year 2019 and included 9 school districts. In 2020, the program expanded to include 32 school districts. Then the program expanded to 56 school districts in 2021.

- The Legislature appropriated around $10 million from the State General Fund in school years 2019 and 2020 to help with things like treatment costs and database creation. The Legislature adjusted the program after the first year to reappropriate unused funds from previous years and to add a local 25% match for the school liaisons hired by participating school districts. Then, in school years 2021 and 2022, the Legislature appropriated around $7.5 million.

- Although the program has been reauthorized and expanded, there has been concern that it has not had the intended impact on school district hiring practices. CMHCs and school districts both need to hire mental health staff from a limited pool of qualified applicants. Before the program, this meant that some school districts and CMHCs were competing for the same staff. This program intended to reduce the competition between districts and CMHCs by increasing collaboration. For districts that had trouble finding mental health staff, the program intended to increase districts’ access to mental health staff without taking them away from CMHCs. In this audit, we were asked to analyze the number of licensed mental health staff school districts have employed in recent years.

Trends in K-12 Mental Health Staffing

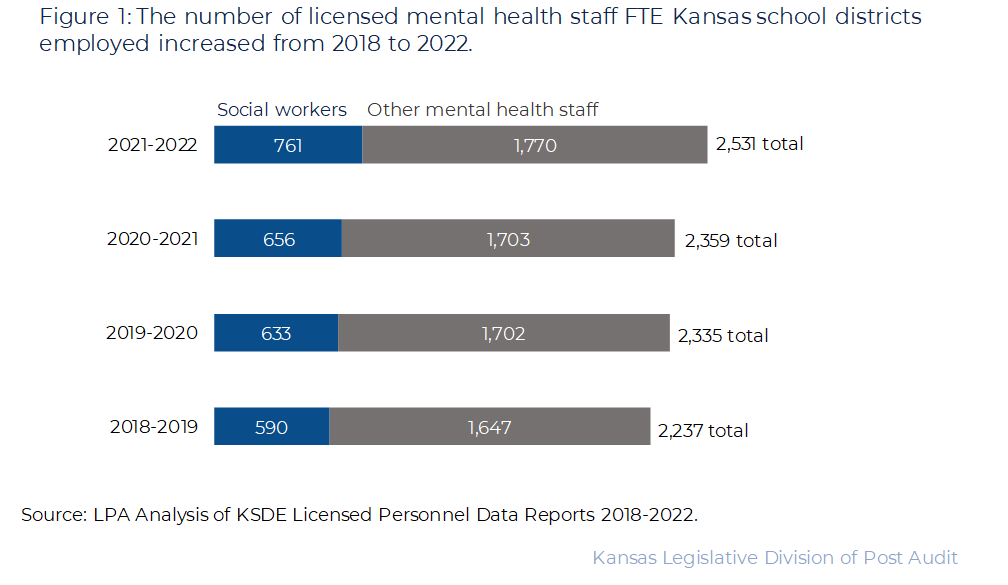

Kansas school districts reported a 13% increase in total licensed mental health staff FTE including a 29% increase in social worker staff FTE from school year 2019 to 2022.

- School districts report the Full Time Equivalent (FTE) for their licensed mental health staff (social workers, psychologists, and counselors) to KSDE each year. These are reported on the licensed personnel report. We used this data to analyze a trend.

- Figure 1 includes the number of mental health staff FTE and the number of social worker FTE Kansas school districts reported employing from 2019 to 2022. As the figure shows, the total number of licensed mental health staff FTE school districts reported increased by 294 (13%) from 2019 to 2022. However, that increase varied by year, type of staff, and district.

- 59% of the total increase in reported mental health staff FTE occurred during the 2022 school year.

- 58% of the total increase in licensed mental health staff FTE was due to an increase in social worker FTE. Psychologists (12%) and counselors (30%) also increased, but by much smaller amounts.

- The 5 school districts reporting the largest increases in mental health staff FTE accounted for 40% of the total increase. For example, Wichita school district reported an increase of 28.5 licensed mental health staff FTE, including an increase of 9.3 social worker FTE. Wichita alone was 10% of the total increase. The next closest district was Goddard school district. It reported employing 25 more mental health staff FTE including 13 more social worker FTE.

- The majority of districts (66%) reported employing the same number of social workers during that time.

School districts don’t report social worker FTE consistently to KSDE, so the FTE trends should be interpreted with caution.

- We found 2 main issues with how districts report their staff. These issues may over or understate our estimates, but the effect is unknown.

- We talked to 5 school districts (out of 286 total) about their mental health staffing and reasons for changes over time. These staff were from Wichita, Garden City, Parsons, Abilene, and Topeka. We selected these 5 school districts because all 5 have participated since the program’s beginning.

- First, some school districts reported their social worker staff FTE based on license. For example, every licensed social worker is reported under the social worker category even if their role in the district is as something else like school counselor.

- Other districts we reviewed reported their social worker FTE based on the role the licensed social workers have in the district. For example, only licensed social workers who function as social workers are reported as social workers. If a social worker is hired as a school counselor, they are reported as a school counselor.

- KSDE staff said districts should report their licensed staff based on role. But KSDE does not currently provide specific guidance to school districts on whether social workers should be reported by license or by title.

- Secondly, two districts said the data we used doesn’t include all the licensed social workers they employ. The districts said they employ licensed social workers in some of their school liaison positions, but these staff FTE are not included in the data because they are submitted on a different report to KSDE.

- KSDE staff also said they expect to see all licensed staff FTE reported on their annual licensed personnel reports. There is also no specific guidance on how schools should report program staff FTE.

- This means KSDE’s licensed personnel report data provides a general idea of overall mental health staffing trends, but it doesn’t give accurate counts for specific staff position FTE or for staff FTE within districts. However, it was the best data available to show the overall trends.

These issues also prevented us from assessing the impact of the program on school district staffing.

- The data we examined includes total FTE of licensed staff that school districts report each year to KSDE. As part of the program, if districts employ liaisons who aren’t licensed mental health staff, they won’t appear in this data.

- Conversely, two districts said they do not include licensed social workers employed with program funds in the data they report to KSDE. This means if districts employ liaisons who are licensed, they may or may not appear in this data.

- As a result, this data can’t be used to draw conclusions about the impact the program has had on the overall trend of licensed mental health staff employed by school districts in Kansas.

School District and CMHC Opinions of the Program

The 5 CMHCs and 5 school districts we interviewed generally reported positive experiences with the program.

- We interviewed 5 CMHCs (out of 26 total) to gather information on their experiences hiring and retaining social workers. We spoke with Labette Center for Mental Health Services in Parsons, Comcare of Sedgwick County in Wichita, Compass Behavioral Health in Garden City, Johnson County Mental Health Center in Mission, and Wyandotte Center for Community Behavioral Health in Kansas City. All 5 CMHCs we interviewed have participated in the program and 3 of the 5 we selected work alongside one of the school districts in our sample. We selected the other 2 CMHCs because the school districts in their communities have shown large increases hiring social workers in recent years.

- Generally, the CMHCs we interviewed reported they had a positive view of the program. This is because they believe it increased the access students have to mental health care resources by placing therapists from CMHCs into schools. Further, the program created communication channels between students, schools, families, and community mental health professionals.

- All 5 districts we interviewed reported the program has had a positive impact on their students. The districts believe the program is fulfilling its intended purpose by increasing the access students have to mental health resources within schools.

The 5 school districts either said the program didn’t have an impact on the number of social workers they hire, or they said it had a small impact.

- The rural school districts reported the program did not have any impact on the number of social workers they employ. That’s because the program gave them funding for school liaisons, and these districts tend to hire individuals who are not licensed social workers as liaisons.

- Urban school districts in our sample reported the number of social workers they employ has increased generally because they have had access to more funding sources in recent years. For example, some districts we spoke with explained that recent COVID-19 funding is part of the reason they were able to hire more mental health staff. The districts said the program funds allowed them to hire some extra staff, but these staff don’t have to be social workers. Thus, they said the impact of the program funding on the number of social workers they hired was small.

However, all 5 CMHCs reported losing staff to school districts.

- CMHCs reported the program resulted in licensed mental health staff they employed (including social workers in some instances) leaving the CMHCs to work for school districts. CMHC’s suggested that placing their staff in schools leads to the staff realizing all the benefits for working for school districts.

- The CMHCs said their staff often leave for the school districts because the CMHCs are unable to match the salary and certain other benefits school districts can offer. For example, CMHCs reported their starting salary for master’s level social workers has been around $46,000 – $49,000 on average in recent years. The school districts we interviewed said they paid master’s level social workers $57,000 per year on average.

- CMHCs also said part of the reason they lose staff to the school districts is because districts can offer jobs with more attractive lifestyles. For example, districts offer jobs with concrete work schedules and an extended summer holiday. CMHCs cannot offer extended holidays and employees often have to work long hours.

- CMHCs also said losing staff had a several lingering effects. When staff leave a CMHC they leave their caseloads behind. The caseloads are then spread amongst remaining staff. This means the remaining staff ends up with much larger caseloads, which CMHCs said has led to increased wait times for patients and burnout for CMHC staff.

- Some CMHCs reported they have vacancies that last for a year or more. One CMHC even reported trouble filling the clinician and case manager positions for the program.

- CMHCs and school districts said there is a widespread shortage of licensed mental health professionals in general. This shortage includes licensed social workers.

Recommendations

- KSDE should develop and distribute guidance to districts on how to report their licensed mental health staff including how to define staff FTE for each category (social workers, psychologists, and counselors).

- Agency Response: The Kansas State Department of Education appreciates the recommendation made by Legislative Post Audit and intends to implement new guidance in the fall of 2022.

Agency Response

On April 8th, 2022, we provided the draft audit report to the Kansas Department of Education. Its response is below. Agency officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions. We made one minor change based on their request.

KSDE Response

Thank you for the opportunity to review and respond to the performance audit, Trends in Social Workers Employed by School Districts.

The Kansas State Department of Education appreciates the recommendation made by Legislative Post Audit and intends to implement new guidance in the fall of 2022.

Sincerely,

S. Craig Neuenswander, Ed.D.

Deputy Commissioner, Fiscal and Administrative Services Kansas State Department of Education