Examining Distributions from the Health Care Provider Tax

Introduction

Senator Jim Denning requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its December 16, 2020 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- What Medicaid services are generating the bulk of payment distributions to non-hospital providers, and what are the add-on percentages for those services?

- Does KDHE adequately monitor and report HCAIP expenditures and revenues?

The scope of our work includes a review of Medicaid non-hospital expenditures in 2019. It also includes a review of various Kansas Department of Health and Environment (KDHE) reports and processes.

We analyzed Medicaid non-hospital expenditures for 2019. We interviewed KDHE officials and members of the Health Care Access Improvement Panel. We also reviewed KDHE reports and reviewed SMART data for 2019 and 2020.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. In this audit, we reviewed how KDHE staff monitor spending for statutory compliance. We identified a few issues that make it difficult for KDHE to precisely monitor compliance.

In 2019, the top 20 procedure codes accounted for 74% of the total Medicaid payments to non-hospital providers.

Medicaid pays for health care services for low-income individuals using state and federal funds.

- Medicaid is a federal program to help cover medical and long-term care costs for certain low-income individuals. This includes children and families, pregnant women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities.

- KDHE contracts with 3 managed care organizations (MCOs) to administer the state’s Medicaid program (KanCare). KDHE pays the MCOs a set amount for each Medicaid beneficiary each month. The MCOs pay providers directly for each service they provide based on reimbursement rates.

- The state and federal government share the costs of Medicaid. The federal government pays for a percentage of the state’s Medicaid expenditures through the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP). Each state’s FMAP depends on its per capita income. In fiscal year 2020, the state’s FMAP was 62%. This means the federal government paid for 62% of Medicaid costs while the state paid for the other 38%.

The Legislature created the Health Care Access Improvement Program (HCAIP) in 2004 to increase the state’s Medicaid reimbursement rates for health care providers.

- The purpose of HCAIP is to increase the number of providers who participate in Medicaid by increasing the reimbursement rates for those providers. If more doctors participate, Medicaid beneficiaries may have better access to health care services.

- Under state law, HCAIP requires most Kansas hospitals to pay an annual tax based on their operating revenue. Currently, hospitals pay 1.83% of the inpatient net revenue it earned in 2010. The 2020 legislature changed the tax from 1.83% of net inpatient operating revenue to 3.0% of net inpatient and outpatient operating revenue. It also based the tax on the fiscal year 3 years before the tax year. However, statute ties these new rates to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approving certain other changes. CMS has not yet approved those changes.

- KDHE combines hospital tax revenues collected under the HCAIP program with federal matching funds to increase reimbursement rates to health care providers. A provider’s total reimbursement rate includes a standard rate for providing services to Medicaid beneficiaries plus a rate increase, called an “add-on percentage.” This is done in two ways:

- For hospitals, the add-on percentage is 23.1% for inpatient services and 25.8% for outpatient Medicaid services. For example, a hospital that provides an outpatient service with a $100 reimbursement rate would receive that rate plus an additional $25.80.

- For non-hospital providers (doctors, surgeons, dentists, etc.), the add-on percentage varies by service. The average percentage across all services is intended to be 25.8%. Larger add-on percentages were assigned to services KDHE wanted to encourage, such as preventative services. For example, a doctor’s office visit to evaluate a new patient gets an add-on of between 65% to 105%, depending on complexity. Conversely, physical therapy gets an add-on of 13%.

- K.S.A. 65-6218(b) establishes a panel to participate in the administration of HCAIP. That panel includes members appointed by various associations, the legislature, attorney general, and governor. Statute gives the panel the authority to determine how HCAIP revenues are used.

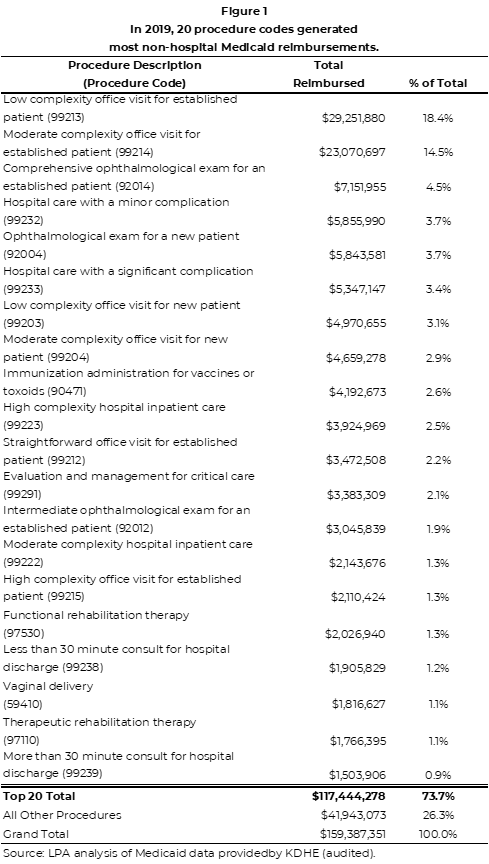

20 procedures generated 74% of total non-hospital Medicaid reimbursements in 2019.

- Health care providers use a procedure code to report what service they provided. The state’s MCOs reimburse the provider the amount for that code.

- We reviewed non-hospital (doctors, surgeons, dentists, etc.) Medicaid reimbursement data for 2019 provided by KDHE. This data shows how much the MCOs reimbursed non-hospital providers by each procedure code for Medicaid services. We did not review hospital providers because that was outside the scope of this audit. Further, we did not evaluate 2020 data because KDHE was still processing claims during our audit. Additionally, 2020 may be an unusual year because of COVID-19.

- In 2019, the Medicaid program paid a total of $159.4 million across almost 900 procedure codes to non-hospital providers for Medicaid services. Figure 1 shows the 20 non-hospital procedures that accounted for the most reimbursements. As the figure shows, the top 20 accounted for 74% of the total payments. The top 20 codes included procedures such as doctor’s office visits, immunizations, and physical therapy.

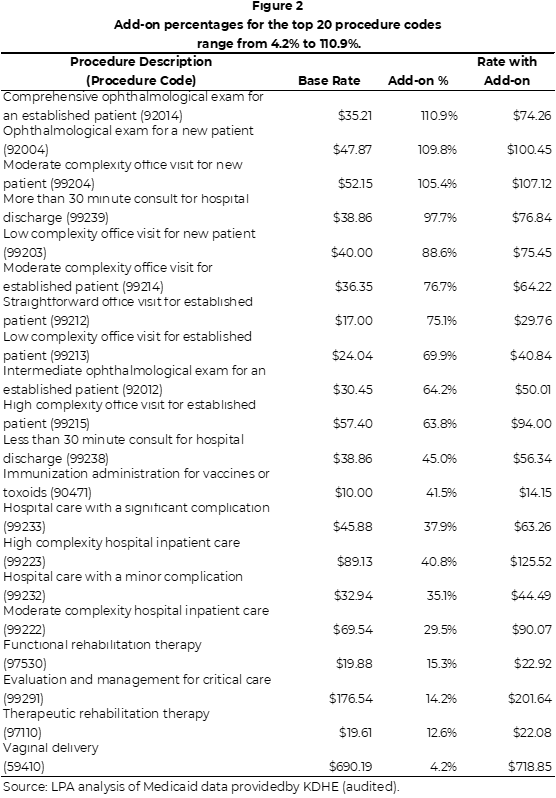

The add-on percentages for the procedure codes that generated the most Medicaid reimbursements for non-hospital providers ranged from 4.2% to 110.9%.

- We looked at the add-on percentages for the 20 procedure codes that generated the most reimbursements for non-hospitals in 2019.

- Figure 2 shows the add-on percentages and base rates for the 20 procedures that accounted for the most non-hospital reimbursements. As the figure shows, the add-on percentages varied significantly across the 20 codes we evaluated. The add-on percentage for delivering a baby was 4.2% whereas the add-on for an office visit to an ophthalmologist was 110.9%.

- KDHE officials told us the add-on percentages were set in 2006 by actuaries and approved by the HCAIP panel. They have not been changed since. Additionally, some procedures had higher add-on percentages because KDHE wanted to encourage some services. For example, regular doctor’s office visits had higher add-ons to encourage more preventative services.

- In 2006, the intent was for non-hospital add-ons to average 25.8% across all the services. However, we estimated the average was 49% in 2019. This is likely because the services that have higher add-on percentages were used more than originally predicted.

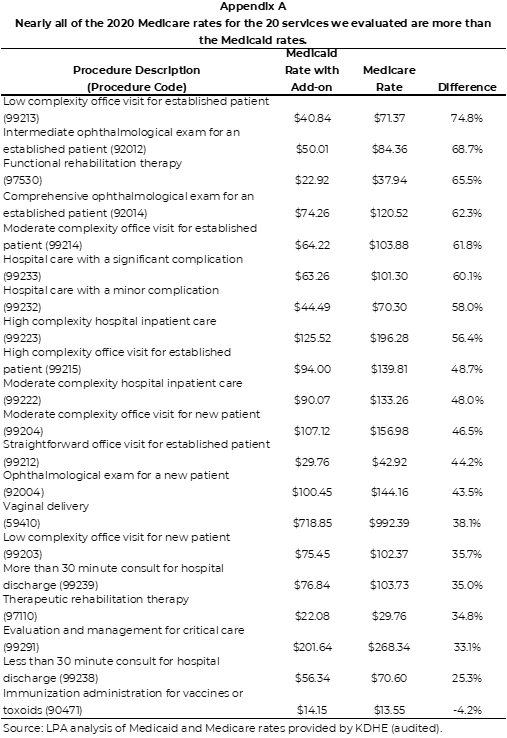

- As part of the audit, we were also asked to compare the Medicaid reimbursement rates (with HCAIP add-on percentage) to Medicare’s reimbursement rates. Medicare is a federal program that pays for the healthcare costs of individuals over 65. That program also reimburses health care providers a set amount based on the service provided. We found that Medicare reimbursement rates for the 20 codes that generated the most non-hospital Medicaid payments in 2019 were an average of 47% more than the Medicaid rates with the add-ons included. Due to time constraints, we did not determine why the rates are different. Appendix A compares the Medicaid and Medicare rates.

Kansas’ Medicaid system has made it difficult for KDHE to adequately monitor and report HCAIP expenditures and revenues.

We evaluated how KDHE monitored HCAIP compliance with state law and whether the agency accurately reported on the program’s finances.

- Although there are several agencies and organizations involved in Medicaid (HCAIP panel, CMS, MCOs, providers), KDHE is ultimately responsible to monitor the HCAIP program and ensure it complies with state law.

- We evaluated whether KDHE was monitoring HCAIP to ensure those statutory requirements were met. Additionally, we evaluated whether the department accurately reports on HCAIP revenues and expenditures.

State statute requires HCAIP revenues to be disbursed in a specific way and that the program be state general fund neutral.

- The HCAIP program is governed by both state law and federal rules as determined by CMS. We reviewed state law and found two requirements for how HCAIP operates.

- K.S.A. 65-6218 (a)(1) requires hospital assessment revenues to be disbursed in specific proportions. Assessment revenues include the tax collected from hospitals and the associated federal matching funds. These funds are combined and paid out to providers through increased rates. The law requires that:

- Not less than 80% of assessment revenues should be disbursed to hospital providers.

- Not more than 20% to non-hospital providers (physicians, surgeons, and dentists).

- Not more than 3.2% to higher education programs.

- K.S.A 65-6218(2) explicitly requires HCAIP to be state general fund neutral, but it has not yet gone into effect. This means that the increases in reimbursement rates must be paid for entirely with hospital tax revenue and federal funds. However, state law only requires this change to go into effect when CMS approves certain changes to the HCAIP program. KDHE officials told us CMS rejected those changes because it violated the state’s KanCare waiver.

Managed care makes it difficult for KDHE to precisely monitor whether the program complies with state law.

- KanCare has reduced KDHE’s ability to precisely track HCAIP expenditures. When HCAIP was first implemented most Medicaid beneficiaries were fee-for-service. Medicaid directly paid providers for the services they provided. KDHE staff told us it was easier to track disbursements under a fee-for-service model where the add-on percentage could be applied and paid directly by service.

- However, under KanCare, tracking expenditures is based on estimates of what portion of the MCO payments are attributable to HCAIP. This is because under KanCare the state pays MCOs a set amount per beneficiary per month regardless of services used. Then the MCOs reimburse the providers for actual services rendered.

- Further, this process is only “backward looking” and does not allow for a real time look at the disbursement split or how much the program is spending. As a result, the department only knows if the program complies with state law after the fact.

In 2020, HCAIP did not comply with the two provisions in state law.

- Based on our estimates using data provided by KDHE, the program did not meet the statutory distribution in 2020. We calculated the numbers using two methods:

- When we calculated how HCAIP assessment revenues were distributed, non-hospital providers received more than the statutory maximum. HCAIP assessment revenues include both the hospital tax revenues and the associated federal matching funds. Non-hospital providers received 32% of the revenues. This exceeds the statutory requirement of not more than 20%. This method aligns with the precise language in state law.

- When we calculated the distribution based on total HCAIP fund expenditures, hospitals and non-hospitals received amounts that were not aligned with statute. Expenditures are the total paid out through increased rates. 74% of the expenditures went to hospitals and 26% went to non-hospital providers. Both percentages violate state law because hospitals received less than the required amount (80%) and non-hospitals received more than the required amount (20%).

- Although legislative intent is for HCAIP to be state general fund neutral, we found the HCAIP program still spends state general funds. We estimated total HCAIP expenditures were about $30 million more than revenues in FY 2020. This includes about $12 million in state general funds.

- KDHE officials were aware that the program did not comply with state law in either area we reviewed.

- We reported these same issues in our 2018 audit of HCAIP. In that audit we found HCAIP funds were not distributed according to state law in 2016. The distributions in those years were similar to what we found for 2020. Additionally, the program was not state general fund neutral. KDHE reports estimated that HCAIP expenditures were $29 million greater than revenues in 2018. This included $13 million in state general funds.

It is unlikely that KDHE can ensure compliance without changes to the HCAIP program.

- To comply with the statutorily required disbursement split, rates likely will need to be adjusted and then reviewed on a regular basis.

- We estimated that HCAIP disbursements to non-hospitals might need to be reduced by as much as 30% to achieve the required distribution. However, this action may affect the number of providers willing or able to provide services to Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Additionally, rates need to be reviewed periodically to ensure the program maintains the statutorily required disbursement. This is because actuaries set the add-on percentages (and resulting MCO payments) based on how Medicaid beneficiaries used services in the past. If usage or other conditions change in a way the actuaries did not expect then disbursements may not meet statutory requirements over time.

- To become state general fund neutral, the program must increase revenues or decrease expenditures. Without one of those two actions it is unlikely that the program can be general fund neutral. Currently, the state has been unable to take either action:

- Legislators amended statute to increase hospital tax revenues in 2020 but that change has not yet taken affect. As a result, the hospital tax rate is still at the previous lower rate (1.83% of 2010 net inpatient revenue). The state can draw down additional federal matching funds by increasing expenditures. To do so, the state would need to increase the hospital tax to have more state dollars to match the federal funding.

- KDHE has not attempted to reduce HCAIP expenditures by reducing reimbursement rates. A member of the HCAIP panel told us reducing reimbursements would be “detrimental” to the program. That is because reducing reimbursement rates may reduce the number of doctors willing to see Medicaid beneficiaries. This audit does not evaluate the potential consequences of a reduction in Medicaid rates.

- KDHE is not able to take many of these actions independently. Some actions will require CMS approval. Others will require that KDHE work with the HCAIP panel. Last, KDHE will likely need to work with MCOs and hospitals to determine how changes to the program might affect them.

Finally, the HCAIP fund report we reviewed does not capture all HCAIP assessment revenues and expenditures.

- We reviewed HCAIP fund reports provided by KDHE for FY 2019 and FY 2020. Those reports are based on expenditure and revenue data pulled from the state’s accounting system (SMART).

- Those reports showed only revenues from the hospital tax, interest, and the related estimated expenditures. It did not reflect total HCAIP assessment revenues which would include hospital tax revenues and federal matching funds. Further, they do not capture expenditures related to the federal funding. As a result, the report provides only a partial picture of the program’s financial position. For example, the 2020 KDHE report shows about $43 million in hospital tax revenue and about $53 million in expenditures. However, total HCAIP revenue and expenditures were an estimated $112 million and $139 million, respectively.

- We were unable to determine whether any KDHE report accurately reflects HCAIP’s total expenditures and revenues. This is because KDHE estimates what part of the money paid to the MCOs is attributable to HCAIP. This estimate is based on actuarial work. We did not review that process or calculations in this audit.

Recommendations

- Because it is very difficult to achieve and maintain, the Legislature should consider whether the statutory split in HCAIP disbursements is feasible.

- KDHE and the HCAIP panel should review and adjust Medicaid reimbursement rates every few years with the goal of maintaining any statutorily required disbursement split.

- KDHE agrees with this recommendation. This recommendation has not been considered in previous years as there is no funding available to pay actuaries to perform this task. The agency is presently unable to implement the recommendation due to a FY21 budget proviso that would prohibit the agency from making any adjustments to hospital or physician rates despite any non-compliance with the disbursement percentages codified in K.S.A. 65-6218. See 2020 SB 66, §70(m) (“ . . . expenditures shall be made by the above agency from such moneys to pay hospitals and physicians at the Medicaid rate established in fiscal year 2020: Provided, that such rate shall not be adjusted prior to January 1 or July 1 following the publication in the Kansas register of the hospital provider assessment rate adjustments described in section 80(l) of chapter 68 of the 2019 Session Laws of Kansas, subsection (l) or, if passed by the legislature during the 2020 regular session and enacted into law, 2020 Senate Bill No. 225 or any other legislation that increases the hospital provider assessment to 3% and includes inpatient and outpatient operating revenue in the hospital provider assessment”).Similarly, the agency’s ability to implement the recommendation in future years depends on whether similar provisos are attached to the agency’s budget going forward. See, e.g., 2021 HB 2007 §80(i), which presently awaits the Governor’s signature (“. . . expenditures shall be made by the above agency from such moneys to pay hospitals and physicians at the Medicaid rate established in fiscal year 2021: Provided, that such rate shall not be adjusted prior to January 1 or July 1 immediately following the publication in the Kansas register of the approval of the hospital provider assessment rate adjustments made to K.S.A. 65-6208, and amendments thereto, by section 9 of chapter 10 of the 2020 Session Laws of Kansas”).

- The HCAIP panel concurs that a regular review of payment rates under the current program would be appropriate, in not more than five-year intervals. Under the new program awaiting approval by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, a specific amount of the total available, within the 20 percent statutory limit, would be set aside for physicians’ rate enhancements and graduate medical education. Each quarter, the remainder would be paid to hospitals based on a percentage of a fixed amount each quarter determined by Medicaid claims paid for each quarter. This new distribution, which includes an increase in the tax rate, will guarantee that the statutory 80/20 split in funds will not be exceeded and that the program will not exceed its revenues. The statutory language necessary to make this change is found in KSA 65-6218 (c), which requires implementing the new program on January or July 1 immediately following approval of the plan by CMS.

Agency Response

On April 6, 2021 we provided the draft audit report to KDHE and the HCAIP panel. KDHE’s response is below. KDHE officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions. The HCAIP panel did not submit a response. We reviewed the information agency officials provided but did not change our findings or conclusions.

KDHE Response

Page 10, Bullet 2: Those reports showed only revenues from the hospital tax, interest, and the related estimated expenditures. It did not reflect total HCAIP assessment revenues which would include hospital tax revenues and federal matching funds. Further, they do not capture expenditures related to the federal funding. As a result, the report provides only a partial picture of the program’s financial position. For example, the 2020 KDHE report shows about $43 million in hospital tax revenue and about $53 million in expenditures. However, total HCAIP revenue and expenditures were an estimated $112 million and $139 million, respectively.

Agency Response: The HCAIP fund reports were created for the HCAIP panel. The HCAIP Panel wanted to be able to verify the amount on the HCAIP fund report with SMART. The HCAIP fund is a revenue fund in the SMART system. CMS does not allow KDHE to draw down the matching federal dollars until there are expenditures, therefore the federal dollars are not in the HCAIP fund reports.

Page 10, Bullet 3: We were unable to determine whether any KDHE report accurately reflects HCAIP’s total expenditures and revenues. This is because KDHE estimates what part of the money paid to the MCOs is attributable to HCAIP. This estimate is based on actuarial work. We did not review that process or calculations in this audit.

Agency Response: The actuaries utilized in Kansashave a very detailed understanding of how the HCAIP increases affect the rates. KDHE would not use the term “estimate” as the actuaries use a very specific calculation to determine the HCAIP amount. The actuaries calculate the amount of each rate cell that is attributable to HCAIP based on the prior two years’ claim experience. This amount is further defined by the type of claim – Inpatient, Outpatient and Physician. Then the actuaries multiply the current members by rate cell in each MCO by the HCAIP amount. The resulting amount is then multiplied by the rate cell’s appropriate FMAP percentage to determine the amount attributable to the HCAIP increase. This amount is recalculated every time the MCO rates are negotiated. The same actuaries that determine the MCO rates also set the DRG rates. Based upon the actuaries’ level of experience and the nature of these calculations, the State is very comfortable referring to the report as accurately reflecting the expenditures and revenues.

Appendix A – Medicare Rates

This appendix compares the Medicaid and Medicare rates for 20 Medicaid procedures.