Evaluating Mental Health and Substance Abuse Initiatives to Improve Outcomes

Introduction

The Legislative Post Audit Committee requested and approved this audit at its September 2, 2020 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- What practices or programs do state-funded mental health and substance abuse providers report using and how well do they appear to be working?

- How do the state-funded mental health and substance abuse treatment practices or programs in Kansas compare to those in other states?

To answer question 1, we interviewed four state agencies and 23 substance abuse and mental health providers (out of about 200 total providers). The providers we selected received state funding through either Medicaid, Senate Bill 123, or were a community mental health center. We interviewed those providers and collected information such as the programs and practices they use, their opinions on the challenges related to providing services, and whether they collected outcomes data. Our results cannot be projected to all providers because we did not choose the providers randomly. We also reviewed academic research related to treatment practices and programs. A lack of outcomes data prevented us from fully addressing question 1, which we discuss in more detail later in the report.

For question 2, we selected 5 states like Kansas in terms of population, median household income, and percent of population that reported illicit drug use. We compared the practices at Kansas substance abuse and mental health providers to those in the similar states. We also analyzed data reported to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration from Kansas and our 5 comparison states.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

Kansas providers reported using many evidence-based programs and practices, but data limitations kept us from assessing how well they are working.

Background

Several state agencies oversee state-funded substance abuse and mental health treatment in Kansas.

- Individuals can seek treatment for substance abuse or mental health concerns in several ways. Those with private insurance can seek treatment through any provider their insurance company has approved. Eligible individuals without private health insurance can seek treatment through state-funded programs.

- In Kansas, four state agencies oversee a variety of programs that pay for individuals to receive treatment:

- The Department of Health and Environment (KDHE) oversees the Medicaid program which pays for certain substance use and mental health treatments for eligible individuals. In FY 2020, Medicaid spent $79.8 million in state money and $150.6 million in federal money on mental health and substance abuse services for Kansans.

- The Department for Aging and Disability Services (KDADS) oversees funds that pay for mental health and substance abuse treatment. The Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant and the Mental Health Block Grants are federal funds that pay for treatment. Individuals who do not have Medicaid or insurance and have an income less than 200% of the federal poverty level are eligible. The state must contribute a maintenance of effort to maintain eligibility for receiving the funds. In FY 2020, KDADS spent $16.8 million in federal money on the block grants and about $150 million in state money for the maintenance of effort. The department also oversees a state-funded treatment program for individuals who have been convicted of a third or subsequent driving under the influence moving violation. Last, KDADS oversees the state hospitals and community mental health centers that provide mental health services to individuals in crisis. In FY 2020, KDADS spent about $118 million in state money on these programs.

- The Kansas Sentencing Commission (KSC) oversees the state-funded treatment program for individuals who have been convicted of certain drug possession crimes. Typically, these individuals receive substance abuse treatment in lieu of prison sentences. This program is more commonly known as Senate Bill 123 (SB 123). In FY 2020, the KSC spent a little more than $7 million in state money on SB 123 drug treatment programs.

- The Department of Corrections (KDOC) oversees state-funded treatment programs for prisoners and parolees. The state contracts with a private company to provide mental health services in adult and juvenile facilities and substance abuse services in juvenile facilities. They also contract with regional alcohol and drug assessment centers to provide assessment and care coordination in adult facilities and to those released on parole. In FY 2020, KDOC spent about $22.5 million in state money on mental health and substance abuse services.

State-funded substance abuse and mental health treatment in Kansas is provided through a network of approved treatment providers.

- An individual who qualifies for state or federally funded treatment can receive it from an approved provider. Depending on where the individual lives, they may have multiple options.

- Approved providers include a network of approximately 200 private, public, and nonprofit providers. Kansas residents can receive substance abuse and mental health services through:

- State mental health hospitals

- Community mental health centers

- Local hospitals

- Federally qualified health centers

- Nursing facilities for mental health

- Private practitioners, like physicians, nurses, and psychiatrists

- The state typically licenses providers to provide services to people who qualify for specific programs. For example, the KSC has approved 131 providers to provide services to SB 123 offenders. Those seeking treatment under SB 123 must use an approved provider. Additionally, KDADS licenses the state’s 26 community mental health centers, which provide services to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis regardless of their ability to pay.

Individuals seek treatment for a wide variety of conditions that often require providers to offer multiple treatment approaches.

- Individuals seek treatment for a variety of conditions including depression, substance use disorders, and bi-polar disorder. In some cases, people seek treatment voluntarily. In other cases, a person may be legally required to seek treatment.

- Which treatment methods a provider chooses can vary based on the severity of the person’s condition. For example, someone with an opioid addiction might need inpatient treatment and medications. Someone with an alcohol addiction may need group or one-on-one counseling. Mental health conditions also vary widely. The treatment for an eating disorder may look substantially different than treatment for schizophrenia.

- Further, some types of illnesses and treatments may be temporary while others are life-long. Someone seeking treatment for situational depression after the death of a loved one may need help for only a short time. However, someone with clinical depression may have that condition for their entire life. They will likely need continual treatment.

- In some cases, a person may struggle with more than one condition at the same time. Sometimes those conditions are related. For example, a person with untreated bi-polar disorder may use drugs to attempt to alleviate some of the symptoms. In that case, they may need multiple types of treatments to address both problems.

- To treat such differing conditions, providers often use a variety of treatment practices and programs. Further, what works for one person may not work for another. As a result, a provider may need to try multiple approaches for the same person.

Kansas Practices and Outcomes

The 23 Kansas substance abuse and mental health providers we interviewed reported using a variety of practices and programs to address their clients’ needs.

- We talked to 23 providers (out of an estimated 200 total) to collect information on the types of programs and practices they use. We selected the providers to get a cross-section of all Kansas providers in terms of location and size. Our results are not projectable because we did not select them randomly. Additionally, programs and practices were self-reported by the providers. Appendix A lists the providers we talked to.

- State law and regulations do not require that providers use any specific programs or practices. However, licensing requirements may require providers to use certain practices. For example, providers approved through the KSC must use cognitive behavioral therapies.

- Providers determine what programs or practices they will offer their clients. Many providers told us they first consider the practices or programs that their license or state contract requires. They also choose practices and programs they think best meet the needs of their clients. Additionally, they consider what financial and staff resources the program or practice might require.

- The 23 providers we talked to reported 95 different practices or programs they used to treat mental health disorders and substance use disorders. A few programs or practices were common across most of the providers we talked to. For example, many of the providers told us they use cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing. Other programs or practices providers use include strengths-based models, integrated dual diagnosis treatment, and eye movement and desensitization and reprocessing.

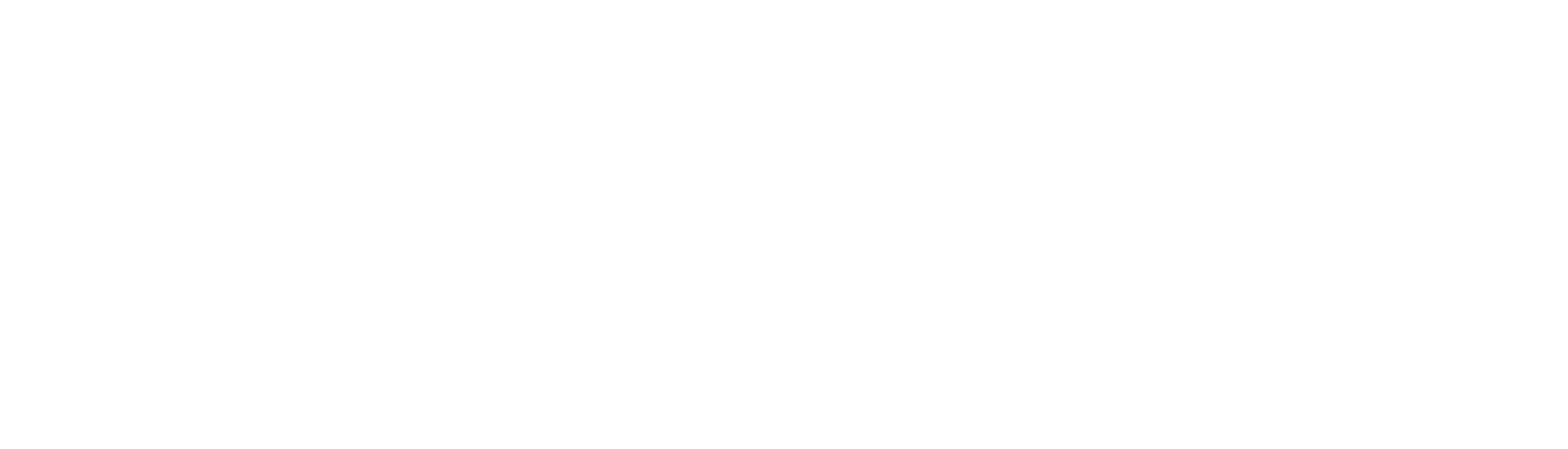

Most of the 11 most common programs and practices reported by 23 mental health and substance abuse providers had at least some research indicating they were effective.

- We evaluated 11 of the 95 programs or practices that were most commonly reported across the 23 providers to determine if research suggested they were effective. For example, all 23 providers reported using cognitive behavioral therapy, 18 reported using motivational interviewing, and 8 reported using a strengths-based model. Figure 1 lists the 11 programs and practices we reviewed.

- For each practice, we reviewed the existing national and international academic research to determine whether the practice is evidence-based. We made that determination on the totality of the research we reviewed. We also relied on research compilations and summaries from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Appendix B lists some of the research we reviewed.

- As Figure 1 shows, 8 of the 11 practices had moderate to strong evidence supporting their effectiveness as a treatment. One treatment (cognitive behavioral therapy) had strong support for its effectiveness. Seven practices had moderate support. For these practices, research found some evidence of effectiveness but noted some caveats:

- Some treatments were found to be effective for certain conditions but not for others. For example, studies found eye movement desensitization and reprocessing is an effective treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder, but more research is needed to determine its effectiveness for other disorders.

- Other treatments found positive effects for some outcomes but not for others. For example, medication assisted treatment appeared effective for improving engagement in substance abuse treatment but was not effective for reducing criminal recidivism.

- For 3 of the 11 practices we reviewed, research found either weak evidence of effectiveness or was inconclusive:

- There was some evidence for the effectiveness of peer support and integrated dual diagnosis, but it should be viewed with caution. This is because some research found only small effects and other research was of poor quality.

- We could not reliably review the effectiveness of the strengths-based model because the existing research was limited and of poor quality.

Many providers reported a lack of funding and staff shortages hindered their ability to provide mental health and substance abuse services.

- Many providers we talked to reported that a lack of funding made it difficult to provide services to more individuals. Specifically, providers noted that Medicaid rates have not been increased since the early 2000s. Additionally, a few providers said the lack of Medicaid expansion in Kansas also plays a role in funding difficulties.

- Many providers reported difficulties in finding enough qualified staff. Some said that licensed clinicians were especially difficult to find. Providers told us they could not compete with other states or other providers in their area in terms of pay.

- A few providers noted other challenges. Some mentioned that the moratorium at Osawatomie State Hospital (OSH) increased demand for community services. In 2015, OSH imposed a moratorium on voluntary admissions due to insufficient space and staff. Some rural providers also reported that lack of transportation makes it difficult for residents in more rural areas to receive the services they need.

A lack of reliable outcomes data and other broader problems kept us from determining the effectiveness of substance abuse and mental health treatment in Kansas.

- Even with good data, differing definitions of success and the transiency of this population make determining the effectiveness of treatment programs or practices difficult.

- Determining what a successful outcome is can vary based on the person and their condition. For someone with a substance use disorder, getting and keeping a job may signal success. However, for someone with schizophrenia fewer psychiatric hospital admissions may indicate success.

- Some mental health conditions are life-long conditions. For an individual with schizophrenia or bi-polar disorder, treatment may help them manage those conditions, but occasional relapse is likely. However, that does not mean their treatment was unsuccessful.

- Individuals seeking mental health or substance abuse treatment tend to be a transient population. It can be difficult to track individuals for more than a short time after treatment ends. As a result, assessing long-term outcomes is not always possible.

- None of the 4 oversight agencies maintain complete and reliable data for all individuals who receive state or federally funded mental health or substance abuse treatment. For example:

- KSC currently does not collect outcomes data.

- KDADS collects data for some individuals who receive state-funded treatment, but it is incomplete and not reliable for our purposes.

- KDHE does not collect outcomes data for those who receive mental health or substance abuse services paid for by Medicaid.

- KDOC periodically contracts with researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of their substance abuse programs. However, they do not consistently collect outcomes data for all participants in their programs.

- Some providers told us they try to collect their own outcomes data. However, they are not required to do this, so it was inconsistent from provider to provider. For example, one large provider told us they send surveys to clients for up to 60 days to collect outcomes data. However, several providers reported they did not attempt to collect any outcomes data.

- The lack of sufficient and reliable data prevented us from determining the effectiveness of state-funded treatment.

Kansas substance abuse and mental health providers use similar practices and programs as five other states.

Kansas substance abuse and mental health providers use similar practices as providers in the other states we reviewed.

- We used 2019 data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to compare Kansas to other states. SAMHSA gathers the data through a periodic survey of all mental health and substance abuse facilities (not just those that receive state funding). All results are self-reported. In 2019, 179 (or 96%) of all Kansas substance abuse providers and 115 (or 87%) of all mental health providers responded to the survey.

- We compared Kansas’ results to five other states that are like Kansas in terms of population, median household income, and percent of population that reported illicit drug use. Those states are Idaho, Iowa, Nebraska, Nevada, and South Dakota. On average, 93% of all providers in those states participated in the survey.

- Figure 2 shows how Kansas substance abuse providers compared to the five other states for the 18 metrics SAMHSA collected and were relevant to the audit. Kansas substance abuse provider services and practices were generally like those in other states. However, there were some differences:

- Kansas had fewer substance abuse providers that offer hospital in-patient services. 3% of Kansas providers offered this service. In contrast, Iowa (6%), Nevada (9%), and South Dakota (9%) providers offered that service at a rate that was two to three times greater than Kansas. The survey did not collect information on bed capacity. As a result, we do not know if this means Kansas truly has less capacity in this area.

- Kansas had fewer substance abuse providers that offered therapies such as dialectical behavioral therapy, contingency management, and community reinforcement. For example, 46% of Kansas substance abuse providers used dialectical behavior therapy. However, on average, 68% of providers in the five other states used it.

- Figure 3 shows how Kansas mental health providers compared to the five other states for the 19 metrics that SAMHSA collected and were relevant to this audit. Again, Kansas was generally like the other states with some exceptions:

- Kansas had fewer mental health providers that offered trauma counseling and dialectical behavioral therapy. For example, in Kansas, 64% of providers reported offering trauma counseling. However, on average, 84% of providers in the five other states did so.

- Kansas has more mental health providers that offered services such as tele-medicine, suicide prevention, and emergency psychiatric services. For example, 58% of Kansas providers offered tele-medicine services versus 46% (on average) in the five other states.

We were not able to compare outcomes in Kansas to other states because the Kansas data is not reliable.

- Providers who receive money through the substance abuse and mental health block grants report a few outcome measures to KDADS for some of their clients. For example, they report things like housing situation and arrests for individuals who received substance abuse services. KDADS submits the data to SAMHSA.

- We tried to compare the SAMHSA data for Kansas and the five other states in 2018, which was the most recent year that data for all 6 states is available. However, the Kansas data was unreliable because much of the outcomes data was missing. If providers did not collect the data for certain metrics, they can still submit what they do have for that individual. As a result, much of the data was missing. Additionally, KDADS does little reliability testing so some of the data that did exist did not make sense. Last, we were unable to determine if those same data reliability issues existed in other states. As a result, we could not compare Kansas outcomes to other states’ outcomes.

Conclusion

We did not draw any conclusions beyond the findings already presented in the audit.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On July 30, 2021 we provided the draft audit report to KDADS, KDHE, KDOC, KSC and the 23 providers we included in Question 1. KDADS officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions. The other auditees chose not to submit written responses. Because we did not make any recommendations, auditees were not required to submit a response.

KDADS Response

Dear Principal Auditor:

Please accept this letter of response to the referenced performance report titled Evaluating Mental Health and Substance Abuse Initiatives to Improve Outcomes.

As the Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services Behavioral Health Services Commissioner, charged with managing mental health services in Kansas I have had the opportunity to collaborate with the Kansas Legislature and the Governor’s Office to increase access to quality services for both adults and children in our state mental health system. Most recently that collaboration has been reflected in the work of the Mental Health Modernization and Reform Interim Committee and its workgroups, which has been reauthorized to convene again during this year’s interim. Last year during the session many of the report’s recommendations were enacted in legislation and signed by the Governor.

During the time I have been serving in this role, KDADS has worked towards implementing recommendations from various taskforce and LPA reports and those of the Governor’s Behavioral Health Services Planning Council. In the last two years we have re-established a State Epidemiological Outcomes Workgroup (SEOW) and a State Evidenced-Based Practices (EBP) Workgroup as part of the Governor’s Behavioral Health Services Planning Council.

SEOWs are a network of people and organizations that bring analytical and other data competencies to prevention. Their mission is to integrate data about the nature and distribution of substance use and mental, emotional, and behavioral (MEB) disorders and related consequences into ongoing assessment, planning, and monitoring decisions at state and community levels. The overall goal for SEOWs is to use data to inform and enhance state and community decisions regarding substance abuse and MEB disorder prevention programs, practices, and policies, as well as promote positive behavioral and mental health over the lifespan.

The Evidence-based Practices (EBP) Workgroup was formed to gain an understanding of the role of EBPs in Alcohol and Other Drug (AOD) and MEB disorder prevention and treatment within KDADS Behavioral Health Services programs. Members of the group work to identify use of “evidence-based” standards or criteria in policy, programs or services provided or funded by the KDADS Behavioral Health Services and examine how EBPs are used across systems of care for both prevention and treatment.

The implementation of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs) will require KDADS to identify and verify fidelity to EBPs included in the criteria for certification of the CCBHCs. KDADS has already begun making some of those decisions which are also reflected in our pre-litigation agreement with Disability Rights Center regarding the increased need for community-based services for individuals with severe mental illness (SMI). Many of these EBPs are mentioned in the report, such as DBT, MAT, and ACT, and the expansion of those EBPs statewide over the next 5-8 years is part of KDADS strategic plans. CCBHCs will be certified over the next 3 years starting in SFY 22.

KDADS is currently working with KDHE to implement the changes to the Medicaid State Plan and KanCare program to allow the CCBHCs to receive a prospective payment system like our Federally Qualified Health Clinics (FQHCs), this change in payment structure will shift behavioral health services from a fee for service model to cost-based reporting. This change in how the costs of the CMHC’s behavioral health services are reimbursed by KanCare MCOs will allow for the CCBHCs to better compete for workforce and help address some of the challenges of being underfunded historically.

KDADS is also currently engaged in a modernization process which is upgrading and replacing systems that have been used for the last 30 years to collect and report data on behavioral health services. The transitional period that agency and its providers are in currently contributed to the difficulty in getting complete data sets for the LPA staff to evaluate. In a few years, KDADS will have statewide electronic health record systems fully implemented and be able to establish API connections with providers to collect and exchange data on patient outcomes and help with tracking patients across multiple providers and hospitalizations.

KDADS seeks to enhance the therapeutic outcome results, improve safety, and create housing and employment opportunities for patients in the Behavioral Health Services system of care. Ensuring providers have technology for patient access & monitoring, enhanced security for safety, and qualified staff for EBPs, makes all the difference in their treatment success. KDADS focus on Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) gives people the hope and help that prevents suicide and other mental health crises. SDOH programs with EBPs for Housing First Pathways and Individual Placements and Supports create opportunities for people with SMI to live and work in our communities through supported housing and employment.

Thank you for consideration of the inclusion of this letter with the final report.

Sincerely,

Andrew Brown, MSW, KCPM

Commissioner

Behavioral Health Services

Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services

Appendix A – Providers

This appendix lists the 23 substance abuse and mental health providers we interviewed as part of this audit.

- A Connecting Pointe – Olathe

- Bert Nash Community Health Center – Lawrence

- City on a Hill – Garden City

- Central Kansas Foundation – Salina

- Comcare of Sedgwick County – Wichita

- Corner House – Emporia

- DCCCA – Lawrence

- Elizabeth Layton Center – Ottawa

- Four County Mental Health Center – Independence

- Heartland Regional Alcohol and Drug Assessment Center – Roeland Park

- Johnson County Mental Health Center – Mission

- Kanza Mental Health and Guidance Center – Hiawatha

- Katie’s Way – Manhattan

- Labette Center for Mental Health – Parsons

- Larned State Hospital – Larned

- New Chance – Dodge City

- Pawnee Mental Health Services – Manhattan

- Spring River Mental Health and Wellness – Riverton

- Substance Abuse Center of Kansas – Wichita

- The Center for Counseling – Great Bend

- Therapy Services – Burlington

- Valeo Behavioral Health – Topeka

- Wyandotte Center for Community Behavioral Healthcare – Kansas City

Appendix B – Cited References

This appendix lists a selection of the publications we relied on for this report. A complete list can be provided upon request.

- EMDR Beyond PTSD: A Systematic Literature Review (September, 2018). Alicia Gomez, Devi Treen, Carlos Cedron, et al.

- Use of Medication-Assisted treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings (2019). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- The Effectiveness of One-to-One Peer Support in Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (November, 2020). Sarah White, Rhiannon Foster, Lucy Goldsmith, et al.

- Efficacy of Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment for Dual Disorder Patients: A Systematic Literature Review (2018). A. Neven, N. Kool, C.L. Mulder, et al.

- Combined Pharmacotherapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adults with Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (June, 2020). Lara Ray, Lindsay Meredith, Brian Kiluk, et al.

- Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on Adult Behavior Change in Health and Social Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Reviews (October, 2018). Helen Frost, Pauline Campbell, Margaret Maxwell, et al.

- Research Evidence on Different Strengths-Based Approaches Within Adult Social Work: A Systematic Review (October, 2020). Anna Price, Latika Ahuja, Charlotte Bramwell, et al.

- The Matrix Model of Outpatient Stimulant Abuse Treatment: Evidence of Efficacy (1994). S Shoptaw, R Rawson, M McCann, et al.

- Psychological Therapies for People with Borderline Personality Disorder (2012). Jutta Winterling, Nick Huband, Klaus Lieb, et al.

- Twelve-Month Outcomes of Trauma-Informed Interventions for Women with Co-Occuring Disorders (October, 2005). Joseph Morissey, Elizabeth Jackson, Alan Ellis, et al.

- Assertive Community Treatment: The Evidence (2008). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.