Evaluating County Government Procurement and Contracting Practices

Introduction

Representative John Toplikar requested this audit, which the Legislative Post Audit Committee approved at its June 1, 2020 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following question:

- Do a selection of county governments have adequate procedures and controls to manage conflict of interests in the procurement and contracting processes?

The scope of our work includes a review of conflict of interest policies and practices for 11 Kansas counties. We selected those counties based on population size (the 5 largest, 3 smallest, and 3 counties with median populations).

We also interviewed county officials and reviewed a sample of contracts. Last, we interviewed officials at the Government Ethics Commission and Secretary of State’s office. Our results cannot be projected to all 105 counties because we did not choose the counties randomly.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

We communicated a minor finding regarding statements of substantial interest forms to Wyandotte County officials.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. In this audit, we found that the smaller counties do not have written policies or practices to adequately identify and manage conflict of interest problems. Representative Tom Burroughs sits on the board of commissioners in Wyandotte County (one of the counties included in this audit). However, the county commission does not play a substantive role in selecting vendors so we did not evaluate his decisions as part of this audit.

For the 11 counties we reviewed, larger counties appeared to have adequate policies and procedures to manage conflict of interests for purchases and contracts, but smaller counties did not.

County governments purchase a variety of goods and services in multiple ways.

- Counties buy many items such as office supplies, software, and equipment. When items are more expensive, the county generally will seek a few quotes to determine who has the best price. When the item is less expensive, county staff are usually allowed to purchase items without comparing quotes.

- The county may also contract with a vendor to provide a good or service. For example, a county may contract with a company to provide and lay asphalt on county roads. Typically, when a county contracts with a company they first seek bids from various companies. Then a committee reviews the bids and chooses a company based on price and quality.

- The individuals responsible for purchasing decisions vary across counties. In some counties, committees—rather than an individual staff person—make decisions for certain purchases. For example, the purchasing department may appoint 3 or 4 knowledgeable staff to determine which vendor offers the best service at the best price. In other counties, a purchasing director or the county commissioners make the decisions.

Individuals who participate in the purchasing process should avoid conflict of interests.

- A conflict of interest occurs when a public official has a financial interest that influences, or appears to influence, the performance of their job duties. For example, it would be a conflict of interest for a county employee to participate in the selection of a contractor when a family member owns one of the bidding companies.

- Conflicts of interest can create many problems. The county may buy a more expensive item which costs the taxpayers more money. Vendors may choose not to participate if they think the process is not fair. The public may lose trust in decision makers.

State law requires counties to address conflicts of interest.

- We identified two state laws that apply to elected officials and staff that govern how counties handle conflict of interests for purchases and contracts. Violations of these laws are a Class B misdemeanor.

- K.S.A. 75-4304 prohibits local government employees or elected officials, in the capacity of their job duties, from contracting with a business that the employee, or the employee’s spouse, has a “substantial interest” in. A substantial interest exists when the employee (or their spouse) has a financial interest in the business that exceeds one of several thresholds. This could come in several forms such as an investment, ownership, or being an employee.

- K.S.A. 75-4305 requires local government employees or elected officials to report substantial interests if a conflict arises. The individual must report this in writing to the county election officer.

Best practices suggest ways counties can identify and manage conflict of interests for purchases.

- We identified many best practices for disclosing and managing conflicts of interest. These best practices came from the National Association of State Procurement Officials and the National Institute of Government Procurement. They include practices such as:

- establish a code of conduct that includes restrictions on those involved in the purchasing process;

- implement a process to evaluate any conflicts that staff report;

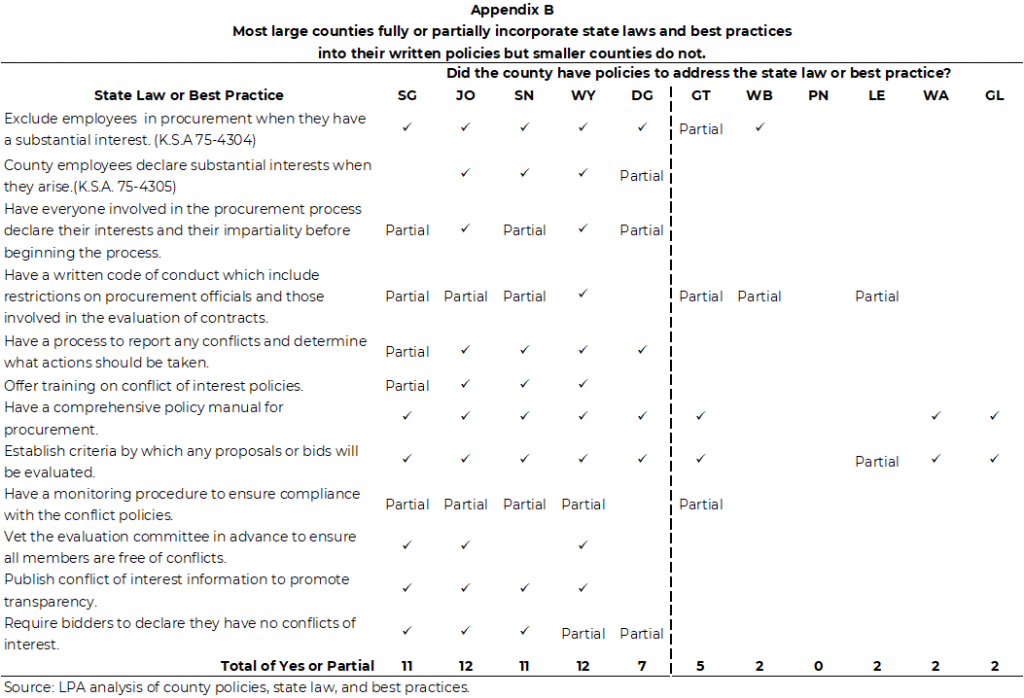

- provide training on ethics and conflict of interest to anyone involved in the purchasing process. Appendix B provides a complete list of the best practices and state laws we evaluated.

- State law leaves the design of most conflict of interest policies and practices to the county. Additionally, counties are not required to implement best practices.

Although good policies are important, counties must rely on the honesty of their employees to detect most conflicts.

- Strong policies can help employees better understand what behavior is unacceptable. It can also eliminate confusion by defining what employees should do when they have a conflict.

- Actively ensuring that conflicts do not exist can be very difficult. Effectively detecting interpersonal relationships and how they relate to a given purchasing decision is time and resource intensive. Further, investing in these resources may not be feasible for many counties.

- As a result, counties rely on employees to honestly self-report any conflicts. Although some counties have policies that aid in reporting conflicts, they still mostly operate on the “honor system.”

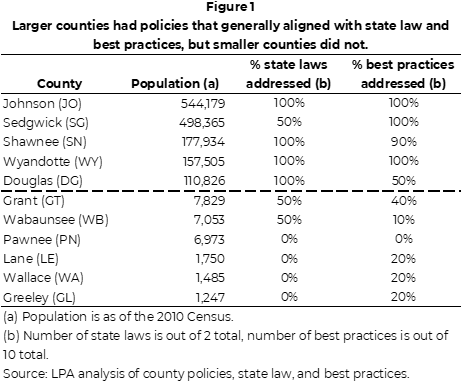

The larger counties we evaluated typically had policies that addressed state law and best practices, but the smaller counties did not.

- We selected 11 counties to determine whether their purchasing and contracting policies or practices aligned with state law and best practices. The 11 counties include the 5 most populous counties, the 3 least populous counties, and 3 counties at the median. Results are not projectable to all 105 Kansas counties because we did not choose them randomly.

- Generally, the 5 large counties had policies that aligned with state law and best practices, but smaller counties did not. As Figure 1 shows:

- 4 of the 5 large counties had policies that aligned with state law.

- 4 of the 5 large counties had policies that included all or nearly all the best practices we identified.

- None of the small or median sized counties had policies that completely aligned with state law.

- None of the small or median sized counties had policies that fully aligned with best practices.

- The smaller counties often relied only on general employee codes of conduct to direct how county employees should manage conflicts. Often the code prohibited employees from participating in decisions that might benefit them financially. However, these counties lacked specific conflict of interest policies.

- This is consistent with what we often see in smaller government entities (towns, school districts, etc.). Smaller counties have fewer staff members and tend to put a premium on trusting their co-workers. As a result, they do not create detailed written policies. Additionally, staff in some of the smaller counties told us that people know each other well so they can avoid conflicts without written policies. However, the lack of specific policies can lead to inconsistent enforcement and a lack of accountability.

Larger counties use a variety of purchasing processes but certain purchases receive little scrutiny for conflict of interests.

- We reviewed purchase documents to determine if counties’ practices aligned with their written policies. We selected 3 purchases made in 2020 in each of the 5 large counties in our selection. We chose purchases of varying amounts and for a variety of products. Our results are not projectable because we did not choose them randomly. We did not conduct this work in the small counties because they did not have detailed written policies.

- As noted earlier, larger counties typically had good conflict of interest policies and processes for purchases made through formal bids or requests for proposals.

- 6 of the 15 items we reviewed (40%) were purchased through bids or more formal processes. Counties generally followed their conflict of interest policies for these 6 items. For example, in Johnson County we saw evidence that all members of a bid committee signed a conflict of interest form. Further, a purchasing manager reviewed those forms before the bid process began.

- However, counties purchase many items through other methods that receive much less scrutiny. 9 of the 15 purchases we reviewed (60%) were made using these types of methods. These methods include:

- Sole-source purchases, which are purchases made when only one vendor can provide the item or service.

- Request for quotes, which is a less formal process that requires the comparison of only a few prices.

- Purchases made through contracts negotiated through the state or other organizations.

- Emergency purchases made when the county must buy the item quickly.

- Although we identified potential weaknesses in how some counties in our selection identify conflict of interests, we did not identify any conflicts. We used information from contracts provided by all the counties and online searches to identify any obvious conflicts. For the contracts we reviewed, we did not uncover any issues.

Other Finding

- One additional law applies to elected officials in general, but not necessarily those involved in contracting or procurement.

- K.S.A. 75-4302a requires candidates for elected local government offices to file a report of substantial interest (SSI) when they declare their candidacy. This includes officials such as county commissioners, county treasurers, sheriffs, and county clerks. The SSI form requires individuals to report what types of businesses or other organizations they have financial interests in. Candidates must file the SSI in the county where the individual declares their candidacy.

- SSI forms can be used to recognize general conflicts of interests for elected officials. These forms also increase transparency and may be of use to voters.

- However, county purchasing staff told us they do not use SSI forms to detect conflicts in purchasing. This was because in many counties elected officials do not typically play a significant role in choosing specific vendors. Additionally, counties have other processes that apply to those directly involved in purchasing decisions.

Conclusion

Identifying conflicts of interest based on personal relationships or financial interests is difficult to do. While elected officials’ statements of substantial interest might increase transparency, they are not particularly useful in identifying conflicts of interest in the purchasing process. Counties must rely on purchasing staff to self-report conflicts on an ad hoc basis (which is all state law requires). However, it is imperative that those involved in the purchasing and contracting processes are clear on what is and is not allowed. Having clear policies, employee codes of conduct, and training help ensure expectations are clear and provide accountability.

Recommendations

- The six median and small counties (Grant, Greeley, Lane, Pawnee, Wabaunsee, and Wallace) should write more detailed conflict of interest and purchasing policies that incorporate the state laws and best practices noted in this report.

County Response

On February 8, 2021 we provided the draft audit report to the 11 audited counties. Their responses are below. Because we did not make a recommendation to the larger counties, they were not required to submit a response. County officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.

Audited Counties’ Response

- Grant County – Grant County has contacted KCAMP attorney assist to guide us in writing a new purchasing policy book. Grant County was not aware our policy manual did not meet today’s standards of compliance.

- Greeley County – Greeley County plans to implement a policy upon advice of counsel and recommendation from the county supervisors, which in Greeley County, is also known as our Commissioners.

- Lane County – Although Lane County does follow certain procedures when it comes to conflict of interest and the procurement process, we do not have these policies in a written document. We are currently working on written documents of both policies and will have them posted on our County website. All employees and officials will be required to sign a certification and attend training on both subjects.

- Pawnee County – Pawnee County does not have a specific written procurement policy. Based on your inquiry, however, the Board of County Commissioners intends to discuss this matter with our Department Heads.

- Wabaunsee County – Wabaunsee County intends to develop policies consistent with the state laws and best practices noted in the report. We are adding this task to our department head meeting agenda and will move forward on an addendum to our personnel policies.

- Wallace County – We have turned this over to a County Commissioner to look into what they need to add to our practices. We will contact one of the other counties listed and see what they have. We will continue to discuss this issue. Our next meeting is February 23, 2021 and we will discuss it then.

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- NASPO Best Practices: Ethics and Accountability. National Association of State Procurement Officials.

- Principles and Practices of Public Procurement (2018). National Institute of Governmental Purchasing.

Appendix B – State Laws and Best Practices

This appendix includes the state laws and best practices we compared county policies to.