Evaluating the Implementation of the Performance-Based Budgeting Process

Introduction

Representative Kristey Williams and Senator Caryn Tyson requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its May 5, 2021 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- Was Kansas’s performance-based budgeting system adequately implemented as outlined in state law?

- Are state agencies providing complete, accurate, and reliable information for the required budget system?

To answer question 1, we interviewed staff with the Division of the Budget (Budget), the Department of Administration, the Kansas Legislative Research Department (KLRD), and the Office of the Revisor of Statutes. We also reviewed templates and training materials related to the required budget system. This work looked at what Budget did to meet statutory deadlines from January 2017 through January 2019.

To answer question 2, we reviewed what information executive branch agencies submitted for the budget system. Our work focused on what agencies submitted from January 2017 through September 2021. We evaluated the completeness, accuracy, and reliability of what 7 agencies submitted in detail. None of our work is projectable to all state agencies.

We did not evaluate how legislative agencies helped implement or satisfy state law. As legislative staff, we cannot objectively evaluate other legislative agencies. We learned about what legislative agencies did but didn’t evaluate whether their actions were adequate or appropriate.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website (www.kslpa.org).

The Division of the Budget generally met the basic requirements in state law, but this doesn’t seem to have meaningfully changed how the state budgets.

Background

Kansas’s budgeting process occurs in stages and involves several agencies.

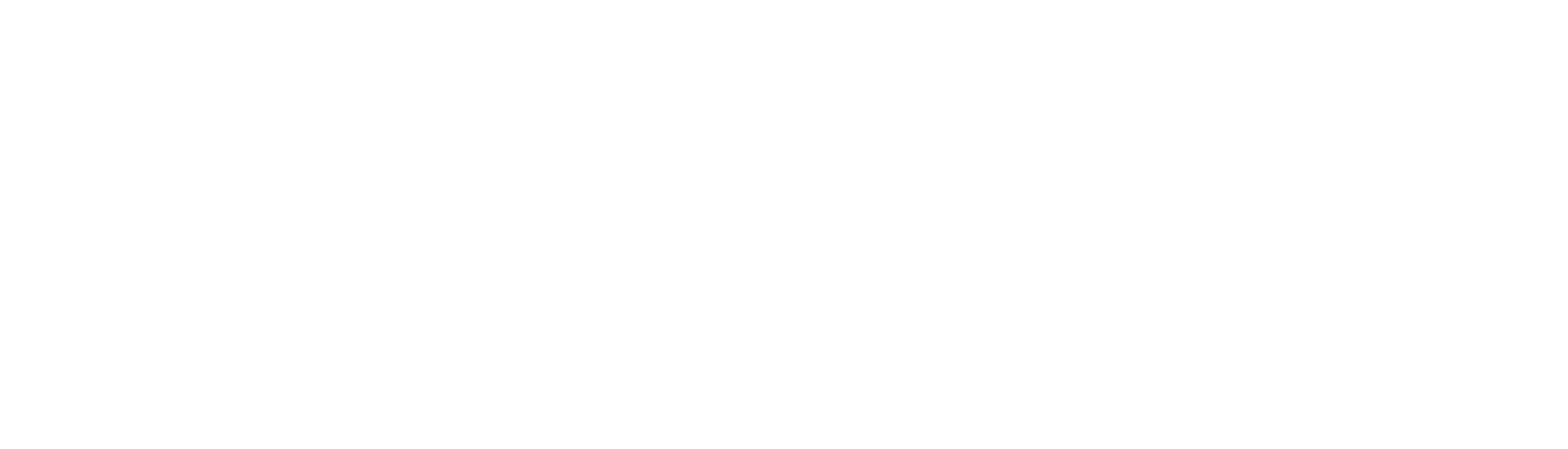

- Figure 1 summarizes the state’s budget process. As the figure shows, the process begins in June, when agencies develop budget requests. Then, the Division of the Budget (Budget) and the Office of the Governor develop the Governor’s budget recommendations. These recommendations are published in January in the Governor’s Budget Report. The Legislature reviews the recommendations and develops appropriations bills during session.

- Kansas Legislative Research Department (KLRD) staff also review agencies’ requests and the Governor’s recommendations. KLRD staff develop budget analyses for legislative committees to review. Those analyses include selected performance measures from agency budget requests.

- Budget and KLRD condense agencies’ budget information for the Governor and the Legislature. This means legislators may not see all information agencies provided in their original budget requests.

- Budget doesn’t work with all agencies in the same capacity. Budget works most closely with the executive branch. By contrast, statute (K.S.A. 75-3718) prohibits Budget from revising the judicial branch’s budget. The legislative branch also manages its own budget. The Legislature exempted Regents universities from the performance-based budget process in 2018.

In 2016, the Legislature passed a law requiring a performance-based budget system.

- K.S.A. 75-3718b became law during the 2016 legislative session. It was based on recommendations from the 2016 Alvarez & Marsal State Efficiency Study. The study recommended Kansas implement a performance-based budget system.

- According to the study, performance-based budgeting would involve considering the results programs achieve with the money they receive. This would be a shift away from focusing on line-items (i.e., categories of expenditures, like salaries) and inputs (e.g., staff positions to fill). The study said this was the best budget method for Kansas to consider, in part because it could be implemented incrementally.

- Statute charges the Secretary of Administration with implementing the budget system. In practice, Budget is responsible for the required processes. Budget is part of the Department of Administration, although it operates independently.

- Budget worked with the Department of Administration, KLRD, and the Office of the Revisor of Statutes to do things like modify the state’s accounting system and provide training to agencies.

Implementing State Law

Statute required the performance-based budget system to be implemented in 3 phases.

- K.S.A. 75-3718b(1) required the development of a program inventory. The inventory was due by January 9, 2017. It should have captured 6 specific elements for agency programs:

- The state or federal statute authorizing each program

- Whether each program is mandatory or discretionary

- A history of each program, including interactions with other agency programs

- Financial requirements for each program

- Prioritization of each program and subprogram

- The consequences of not funding each program and subprogram

- K.S.A. 75-3718b(2) required an integrated budget fiscal process. It was due by January 6, 2018. It should have accomplished 2 things:

- It should have aligned agencies’ budgets with their program inventories. Agencies could then report expenditures by the programs and subprograms in their inventories.

- It should have aligned IBARS, the state’s budget system, with SMART, the state’s accounting and reporting system. This would make the programs and subprograms in the systems match.

- K.S.A. 75-3718b(3) required a performance-based budgeting system. It was due by January 14, 2019. It should have included at least 2 features:

- The system should have incorporated outcome-based performance measures for state programs.

- It should have made it easier to compare program effectiveness across state and political (e.g., county or city) boundaries.

Budget developed processes that satisfy the basic statutory requirements, with one exception.

- We interviewed stakeholders to learn what they did to meet statutory requirements. We interviewed staff with Budget, the Department of Administration, KLRD, and the Office of the Revisor of Statutes. We also reviewed relevant documentation. For example, we looked at the training and guidance materials Budget gave agencies. We also reviewed some of what Budget required agencies turn in.

- Budget developed a program inventory by January 2017, but it did not include program interactions.

- Budget worked with KLRD to develop a template for agencies to fill out. Budget and KLRD also put on trainings to explain how to fill out the inventory. Budget staff told us they gave the completed inventories to KLRD. KLRD staff told us they gave the inventories to House budget committees and Senate subcommittees. KLRD did not give inventories to all legislators.

- Budget did not require agencies to explain how their programs interact as required by K.S.A. 75-3718b(1)(D). Budget staff told us requiring this level of detailed information would bog down agencies. Budget staff said such detail wouldn’t help achieve the goal of developing performance measures for programs. The effect of this was likely limited because the inventory was only developed once and not all legislators received a copy.

- Budget created an integrated budget fiscal process by January 2018. Budget and agencies identified changes they needed to make in IBARS or SMART to align their budget reporting with their program inventories. Budget updated IBARS and the Department of Administration updated SMART.

- Budget took steps to implement a performance-based budget system by January 2019.

- This system mainly required agencies to review, consider revising, and get feedback on the performance measures they had previously been submitting. This emphasized having agencies develop ways to measure their performance through outcome measures. Budget created a template for agencies to map performance measures to their programs and subprograms. Budget and KLRD also provided training to help agencies develop outcome-based measures.

- Budget continues to require agencies to submit performance measures in their budget requests. Budget also requires agencies to support enhancement requests with performance measures. The budget instructions say Budget won’t consider enhancements that don’t include performance measures.

The performance-based budget system doesn’t seem to have changed the way the state makes budgeting decisions.

- The purpose of creating a performance-based budget system is to use information about how well agencies are performing to inform budget decisions. It involves focusing on what a program will achieve with the funding it receives.

- We didn’t see any evidence this was happening systematically. For example, we talked to 7 executive branch agencies, and some said they didn’t use performance measures to support their budget requests. They said their requests were mainly driven by operational needs, like staff needs. And Budget told us performance measures only inform executive budget decisions some of the time. Thus, it appears that at least for some agencies, performance information isn’t systematically used to make budget decisions, even though Budget collects that information.

- State agencies reported performance measures even before the performance-based budget law was passed in 2016. But that information focused on how much agencies were doing. It didn’t focus on how well agencies were doing. For example, an agency might have reported on how many inspections it did instead of whether those inspections increased compliance with legal requirements. Most of the 7 agencies we talked to told us the new budget processes didn’t change the way they do business. Some agencies further told us they would have continued reporting on their performance like they had in the past regardless of the performance-based budgeting statute.

- We didn’t evaluate the extent to which the Legislature uses the information Budget collected to make decisions because we’re not independent from the Legislature. But we know not all performance information makes its way to legislators. For example, the Governor’s Budget Report may only list a few performance measures an agency submitted. If legislators don’t request and review an agency’s original budget request, they may not see all performance information an agency submitted. This would limit the extent to which legislators can use performance information to make decisions.

That’s partly because statute is very general and allows a lot of discretion.

- Statute as written allows room for interpretation. For example:

- State law doesn’t say whether agencies should submit program inventories annually. Budget asked agencies to submit program inventories in December 2016. Budget doesn’t require agencies to update the program inventories each year. This may be problematic because the inventories will become outdated and less useful over time.

- Statute doesn’t say how much information Budget should have collected about programs’ financial requirements (e.g., how much the state must spend to get federal funding) in the program inventory. Budget asked agencies to identify whether their programs had financial requirements as a yes or no option. Budget didn’t ask agencies what those requirements were. This may be a problem if legislators wanted more details about these requirements. For example, when developing a budget bill, legislators may want to know how much the state has to spend on a program to get federal funding.

- Statute doesn’t specify whether all programs are required to have outcome-based performance measures. It’s written in a way that could mean all programs need multiple outcome-based performance measures. Or it could mean only some programs need at least one outcome-based measure. Budget didn’t require outcome-based measures for all agencies’ programs. This may be a problem if legislators wanted all programs to have outcomes.

- State law also doesn’t specify who’s responsible for using the required information or how they should use it. Budget has generally collected the information required by statute. But it’s not clear who this information should go to or what should happen next. Some legislators expressed concern because they haven’t seen the information required by statute. Others expressed concern about the quality of the information they’ve seen. These issues limit how legislators can use performance information to inform budget decisions.

Incorporating aspects of other states’ performance-based budget legislation may improve Kansas’s statute.

- We looked at performance-based budgeting in 2 other states: Mississippi and New Mexico. We looked at Mississippi because it is working to overcome challenges like Kansas’s. We looked at New Mexico because it’s regarded as having a strong system.

- Mississippi and New Mexico have clearer performance-based budget frameworks than Kansas. For example:

- These states’ legislation defines key terms. Kansas’s legislation doesn’t. For example, New Mexico’s legislation includes definitions for terms like “outcome” and “performance-based budget.”

- These states’ legislation also defines clearer roles for the legislative branch. For example, Mississippi’s legislation makes legislative staff responsible for collecting program inventories. It also says a legislative committee can use performance information in appropriations bills if they find it practical to do so. Kansas statute doesn’t have this specificity even though the Alvarez & Marsal study said most performance-based budget laws define a clear role for the legislative branch.

- There may be additional promising practices in other states. The Alvarez & Marsal study identified Iowa, Oregon, Louisiana, and Oklahoma as potential models.

State agencies didn’t always submit complete, accurate, or reliable information for the budget system.

Background

We did a high-level review of 79 executive branch agencies to see whether they submitted required information to Budget.

- We based our review on 79 state agencies in the fiscal year 2020 Governor’s Budget Report. The report summarizes budget information for each state agency.

- We didn’t include Regents universities or legislative agencies in our review.

- We excluded Regents universities because the Legislature exempted them from statutory requirements.

- We excluded legislative agencies because of independence issues. Professional auditing standards prevent us from evaluating agencies within the same branch of government. However, we wanted to disclose that our office has only submitted performance measures in two of the last four years they were required (2018 and 2021).

- We checked to see whether the 79 agencies submitted required information to Budget. We didn’t check the quality of what agencies submitted. For example, we checked to see which agencies submitted program inventories. We didn’t verify each agency submitted a complete or accurate inventory.

- We don’t discuss what agencies submitted for the integrated budget fiscal process. The process was the second phase required by statute. It required Budget and the Department of Administration to align the state’s budget and accounting systems. This required input from agencies. But Budget didn’t centrally track agencies’ input. Budget staff said they sometimes used informal communications (e.g., phone calls) to get input. And finally, not all agencies needed to request changes because their program structures didn’t change. We saw evidence some agencies provided input. But we couldn’t determine whether some agencies didn’t provide input when they should have.

- The time periods we evaluated varied depending on what part of the process we were checking. For example, we looked at whether agencies submitted inventories by January 9, 2017. That was the statutory due date.

We also reviewed 7 agencies’ information in detail to evaluate its quality.

- Figure 2 summarizes the 7 agencies we reviewed in detail. Those 7 agencies were the Department of Education (KSDE), the Department of Corrections (KDOC), the Department of Revenue (KDOR), Kansas Highway Patrol (KHP), the Office of the State Bank Commissioner (OSBC), the Kansas Human Rights Commission (KHRC), and the Kansas Dental Board (KDB).

| Figure 2: We selected 7 agencies to review based on expenditures and staffing. | ||

| State Agency | FY 20 Expenditures (millions) | Number of Staff |

| Department of Education | $5,531 | 264 |

| Department of Corrections | $222 | 507 |

| Department of Revenue | $105 | 1,089 |

| Kansas Highway Patrol | $99 | 881 |

| Office of the State Bank Commissioner | $10 | 107 |

| Kansas Human Rights Commission | $1 | 23 |

| Kansas Dental Board | $0.4 | 3 |

| Source: The State of Kansas Governor’s Budget Report, Fiscal Year 2022 (unaudited) | ||

| Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit | ||

- We selected these agencies because they varied in size and in the types of services they provide. Because this was a judgmental selection, our results are not projectable across all state agencies.

- We checked to see whether the 7 agencies submitted complete program inventories.

- We looked only for information that statute required.

- We didn’t verify agencies submitted correct information for all parts of the inventory. For example, we didn’t verify agencies reported the correct statutory citations for their programs. We only checked to see that they provided a response that appeared reasonable.

- We reviewed a selection of these 7 agencies’ performance measures. Some agencies submitted a lot of performance measures, and it wasn’t feasible for us to review them all. For the ones we selected, we checked to see if the agency provided outcome measures that were valid. We also checked whether the measures were accurate and based on reliable data.

Agencies’ Program Inventories

4 of 79 agencies didn’t submit program inventories.

- The Abstracters Board of Examiners and the Board of Veterinary Examiners didn’t submit program inventories.

- Budget said the Abstracters Board is very small. It had no FTE positions in FY18 and less than $25,000 in expenditures. Budget said it didn’t make sense to have the board submit an inventory.

- We couldn’t determine why the Board of Veterinary Examiners didn’t submit a program inventory. Neither the board nor Budget could explain why the board didn’t submit an inventory. The board used to be part of the Department of Agriculture. It became independent in 2016. The timing of its independence may have caused it to slip through the cracks.

- The Office of the Governor and the Attorney General didn’t submit inventories. Budget staff told us they can’t compel agencies led by elected officials to submit program inventories.

- Budget didn’t identify someone in the Governor’s Office we could ask about this. This was because the inventories were due under a prior administration.

- The Office of the Attorney General told us the agency submitted an inventory that was the basis of the budget narratives they currently use. However, the office was unable to find the communication in which it sent the inventory to Budget.

- This work was only to check whether each agency submitted an inventory. We didn’t check whether all inventories were complete.

5 of the 7 agencies’ program inventories we reviewed for quality didn’t include all required information.

- As previously discussed, statute required program inventories to capture 6 specific elements for agencies’ programs:

- The state or federal statute authorizing each program

- Whether each program is mandatory or discretionary

- A history of each program, including interactions with other agency programs

- Financial requirements

- Prioritization of each program and subprogram (i.e., how important each program is)

- The consequences of not funding each program and subprogram

- Figure 3 summarizes our review of the 7 agencies’ inventories and performance measures. As the figure shows, 2 agencies’ inventories had significant deficiencies.

- KDOC didn’t rate the priority levels of any of its subprograms. It also didn’t provide histories for 9 of its 12 programs. It listed statutory citations instead of providing narrative information.

- KDOR didn’t rate the priority of any of its programs. It only rated the priorities of its subprograms.

| Figure 3: The issues in the 7 selected agencies’ information submissions varied. | |||

| State Agency | Program Inventory | Performance Measures | |

| Outcome-Based | Accurate & Reliable | ||

| Kansas Human Rights Commission | ✗ | ✓ | (a) |

| Kansas Dental Board | ✓ | ✗ (b) | ✓ |

| Kansas Highway Patrol | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Office of the State Bank Commissioner | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Department of Education | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Department of Revenue | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Department of Corrections | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| ✓ = no issues identified, ✗ = minor issues identified, ✗ = significant issues identified | |||

| (a) We couldn’t determine how accurate and reliable KHRC’s measures were. We were only able to review 1 of 9 measures for accuracy and none for reliability. | |||

| (b) We think state law intended for each agency to report a few outcome-based measures. KDB only had output measures. However, statute doesn’t clearly require all agencies to have outcome-based measures. Based on KDB’s activities, we didn’t think this was a problem as described more in the report. | |||

| Source: LPA review of selected agencies’ performance-based budgeting information submissions | |||

| Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit | |||

- As the figure also shows, 3 other agencies’ inventories had minor issues. For example, KSDE didn’t rate the priority levels of its administrative subprograms. We thought this was a minor issue because it affected only 1 of the department’s programs. By contrast, the KDOC didn’t provide priority levels for any subprograms.

- Causes of incomplete inventories varied. In some cases, it appears agencies simply forgot to provide a few pieces of information. In other cases, agencies had tentative explanations for the issues we noticed. For example, KDOC officials speculated they didn’t prioritize subprograms because their subprograms are all statutorily required. But they couldn’t be sure due to turnover in management. Budget didn’t have a consistent, centralized process to review what agencies submitted.

- The effects of these issues are likely minor because of how Budget implemented the program inventory. The program inventory was a one-time process that agencies used to develop performance measures.

Agencies’ Performance Measures

All but 2 of 79 agencies had performance measures in the fiscal year 2020 Governor’s Budget Report, but it’s not clear how many agencies reevaluated their measures for performance-based budgeting.

- Budget required agencies to submit performance measures as part of the performance-based budget system requirement. Agencies had historically reported performance measures to Budget. But agencies should have reevaluated their measures for the new budget system. Budget and KLRD staff reviewed agencies’ measures and provided feedback.

- Budget didn’t keep documentation showing which agencies submitted reevaluated performance measures. Budget had documentation for 57 of 79 agencies. It’s possible some of the remaining 22 agencies submitted documentation and Budget simply didn’t keep it. For example, Budget didn’t have evidence 2 of the 7 agencies we reviewed in detail submitted performance measures. But based on our work with those agencies, they had. This means we couldn’t readily identify which agencies submitted measures.

- But based on the fiscal year 2020 Governor’s Budget Report, all but 2 of the 79 agencies we reviewed had performance measures listed. This means agencies generally submitted performance measures to Budget. The only agencies that didn’t were the Office of the Governor and the Judiciary. Judiciary officials told us they submitted measures to Budget. They showed us measures they sent to Budget and said they weren’t sure why the Budget Report didn’t have measures listed.

- But the fact that agencies had measures in the Governor’s Budget Report doesn’t necessarily mean agencies revised their performance measures for the performance-based budgeting system. They could have continued reporting the same measures they had in the past.

- Further, the Governor’s Budget Report only contains some of the performance measures agencies submit to Budget. Budget may change the measures it features in the report from year to year. This means we can’t use the budget reports to determine whether agencies revised their measures for the performance-based budget system.

We reviewed some of the 7 selected agencies’ performance measures to see if they were valid and outcome-based.

- Statute required a budget system that included outcome-based performance measures for state programs. We expected each agency to submit at least a few outcome-based measures.

- We thought measures were outcome-based when they showed the ultimate effects of agency activities. In other words, we thought they helped show whether an agency or program is achieving its objectives. By contrast, we thought measures were output-based when they showed how much an agency is doing.

- For example, say a program’s purpose is to increase highway safety.

- An output measure for that agency might be the number of DUI arrests made. This reflects how much the agency is doing to achieve its mission.

- An outcome measure for that agency might be change in highway fatality rate. This shows whether the agency’s activities (i.e., arresting drunk drivers) is effective at improving highway safety.

- Valid measures are measures that help assess how an agency is performing.

- To determine whether a performance measure was valid and outcome-based, we analyzed 6 aspects. If the answers to these questions were all yes, then we considered the measure to be valid and outcome-based.

- Does the measure concern an outcome (reflect the effectiveness of an agency’s activities) rather than an output (reflect how much an agency does or produces)?

- Is there a direct link between the measure and the associated program’s purpose?

- Is the measure quantifiable?

- Can the measure be measured consistently over time, without gaps in data?

- Can the agency plausibly influence its performance on the measure?

- Can a change in the measure say something about the quality of the agency’s performance?

- Deciding whether measures were valid and outcome-based required professional judgment. Someone’s interpretation of whether a particular measure is valid and outcome-based is subjective. This is at least in part because the outcomes agencies measure may be affected by things besides what agencies do.

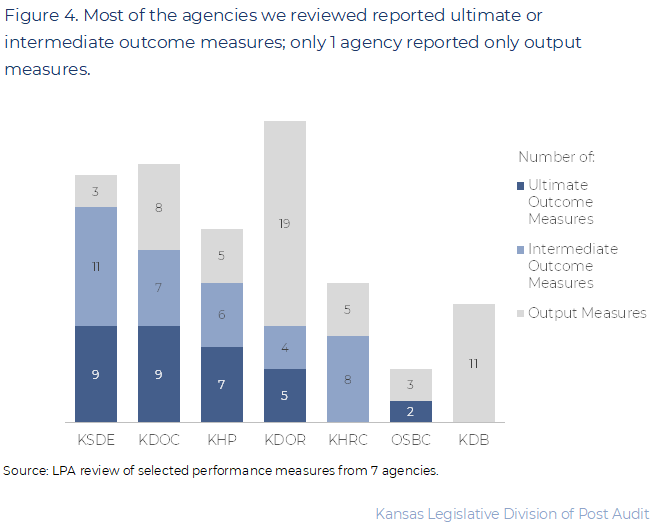

6 of the 7 agencies we reviewed submitted at least some valid outcome measures.

- As Figure 4 shows, we reviewed between 5 and 28 performance measures from each of the 7 agencies we selected. We reviewed a total of 122 performance measures. All measures were in the budget requests the agencies submitted to Budget for the upcoming 2023 fiscal year.

- 32 (26%) of the measures we reviewed were valid and reflected an ultimate outcome. These types of measures most clearly illustrate whether agencies’ activities are effective.

- For example, a KDOR measure shows how often liquor license holders sell alcohol to underage individuals in tests. This shows how effective the department’s regulation activities are at stopping alcohol sales to minors.

- 36 (30%) measures were valid and reflected intermediate outcomes. They may also have reflected whether a process was working well. These measures don’t directly show how well an agency is doing at achieving its goals. But they do show the more immediate effects of agencies’ activities. They measure more than just how much an agency is doing or producing (i.e., they’re not simply output measures).

- For example, KHP reports the percentage of trucks its mobile units identify as illegally overweight. One of KHP’s goals is to protect highway infrastructure and enhance public safety. The measure doesn’t directly show KHP has protected infrastructure or enhanced safety. That’s because KHP’s mobile units represent only a small fraction of truck weighs (e.g., about 5,500 in FY 21), so it paints an incomplete picture. KHP weighs many more trucks at fixed weigh stations (e.g., about 600,000 in FY 21). But based on changes in the measure, one could make inferences about whether the program is achieving its goal. For example, a decrease in the percentage of overweight trucks stopped may mean less wear on highway infrastructure.

- The remaining 54 (44%) measures were output measures. They measured how much agencies did or produced. They didn’t show the effects of agencies’ activities. We think it’s okay that agencies submitted these types of measures, too. Statute doesn’t say agencies can’t or shouldn’t submit output measures.

- For example, KHRC’s goal is to prevent discrimination. It reports the number of people it trains on discrimination. But that doesn’t tell us whether the trainings are effective at reducing discrimination. KHRC tries to measure the effectiveness of its trainings through surveys. It doesn’t report this as a performance measure, but it discusses it in its budget request. KHRC officials were agreeable to reporting it as a performance measure in the future.

1 of the 7 agencies we worked with only had output measures, but we didn’t think this was a problem.

- Based on our criteria, the Kansas Dental Board (KDB) had no outcome measures. It had only output measures.

- We generally expected agencies to have at least a few outcome-based performance measures. We thought this would reasonably satisfy the intent behind statute.

- But as previously discussed, it’s not clear statute requires all agencies to have outcome-based measures. Further, outcome measures may not make sense for all agencies or programs.

- For example, KDB officials said their activities were mainly about managing inputs and outputs (e.g., number of dentists to inspect). They told us they don’t have much of an ability to drive or measure outcomes. They said inputs and outputs are the main drivers of their budget requests, not outcomes.

- Whether all programs or agencies should have outcome-based performance measures is a policy decision. It may be that not all agencies should be subject to the same requirements. The question is what information policymakers need for budget decisions. In some cases, outcome measures may not be the most relevant performance information.

We also reviewed the 7 agencies’ performance measures to see if they were accurate and based on reliable data.

- Of the 122 measures we reviewed for validity, we reviewed 68 to see whether they were calculated accurately and based on reliable data. We reviewed between 5 and 15 measures for each of the 7 agencies. For each measure, we checked what the agency submitted for at least one of fiscal years 2019 through 2021.

- The scope of our accuracy and reliability review was limited.

- To assess accuracy, we checked whether agencies included all relevant data in their calculations. We also checked whether their calculations made sense.

- To assess reliability, we checked whether the data used to calculate measures had obvious errors (e.g., outliers or illogical values). We also considered whether the data were measuring the correct things. We didn’t do in-depth reviews of agencies’ documentation.

- We couldn’t assess accuracy or reliability for many measures. This was generally because doing so would have required significant additional work. However, that work wouldn’t have likely changed our answer to the audit question.

- If we couldn’t assess reliability, we still tried to assess accuracy. For example, 1 of KDOC’s measures is the number of offenders under parole supervision. We couldn’t verify the data counted all offenders who were under parole (i.e., that the data was reliable). But we could check to see that KDOC added the categories of offenders under parole correctly.

3 of the 7 agencies had significant accuracy or reliability issues with 1 or 2 of their measures.

- As Figure 3 shows, agencies had accuracy and reliability issues of varying magnitudes. 3 agencies had significant issues with a few measures. These issues would cause someone to draw an incorrect conclusion about agency performance.

- 2 of the 11 measures we checked for KHP were based on significantly unreliable data and inaccurate.

- KHP reports the percentage of trucks its mobile units stop that are illegally overweight. For fiscal year 2021, KHP reported 30% of the trucks stopped were overweight. But the actual percentage was 57%. The error was due to a problem in the data used to calculate the measure. About 5,000 truck weighs were incorrectly recorded as mobile unit weighs. KHP should have used those weights to calculate performance for a different measure. Earlier, we said KHP’s mobile unit weighed about 5,500 trucks in fiscal year 2021. This means the data incorrectly showed the mobile unit weighed about 10,500 trucks. KHP revised their data after we discussed this issue with them.

- KHP also reports the percentage of homeland security funding proposals it reviews within 30 days. KHP reported reviewing 100% of proposals within 30 days in fiscal years 2019 and 2020. But KHP officials told us they don’t actually do this review process anymore. The measure isn’t based on reliable data because no data exist. There is no process for KHP to measure.

- 1 of the 15 measures we checked for KDOC was significantly inaccurate.

- KDOC reports the number of victim notification letters it sends out. In fiscal year 2019, it reported sending out 15,759 letters. But based on our review of KDOC documentation, KDOC actually sent out 19,449 letters. KDOC staff told us this was due to a clerical error in reporting. It was not because the data about letters was inaccurate.

- 1 of the 10 measures we checked for KSDE was based on unreliable data.

- KSDE reported for fiscal year 2021 the percentage of high schools with individual plan of study programs with features like guest speakers or career fairs. KSDE used a survey to collect that information. But we noticed some of the schools surveyed were not high schools. The data was unreliable because it measured schools it shouldn’t have. We were unable to pinpoint the magnitude of this error. KSDE said the error was due to the text of the measure not being updated to align with the data.

- We also identified other minor accuracy or reliability issues in 4 agencies’ (KDOC, KDOR, KHP, and OSBC) measures. These issues were minor because they wouldn’t cause someone to draw an incorrect conclusion about agency performance. For example, KDOC reported it provided substance abuse treatment to 737 offenders. But the data showed only 735 offenders received treatment (<1% error). We discussed these minor data accuracy issues with agency officials during the audit.

Conclusion

We did not draw any conclusions beyond the findings already presented in the audit.

Recommendations

- The Legislature should consider amending statute to set clearer expectations. This could include more clearly defining roles for agencies like Budget and the Legislature. It might also say what should be presented to the Legislature (as a whole or by committee). Finally, the Legislature might also consider requiring only some agencies to participate in performance-based budgeting.

Agency Response

On December 8, 2021, we provided the draft audit report to the Dental Board, the Departments of Administration, Corrections, Education, and Revenue, the Division of the Budget, Highway Patrol, the Human Rights Commission, and the Office of the State Bank Commissioner. We made minor changes based on their feedback.

Because we did not make recommendations to the audited agencies, they were not required to submit responses. The Dental Board chose to submit a response. Its response is below. Agency officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.

Dental Board Response

Dear Mr. Stowe:

I am in receipt of the Legislative Post Audit (LPA) draft report, Evaluating the Implementation of the Performance-Based Budgeting Process (January 2022). I have read the draft report in its entirety. I sincerely appreciate the opportunity to respond to the draft report regarding performance-based budgeting (PBB).

Quite notably, LPA did not make any recommendations for the Kansas Dental Board (KDB) relative to its findings with PBB, meaning a written response to the report is optional. As the KDB’s Executive Director for the past ten (10) years, however, I determined that a written response is appropriate to ensure continuity and completion of the LPA process.

After a thorough review of the draft report, I submit that the KDB fully complied with all statutory, budgetary, and implementation requirements in the PBB process. As a preliminary note, the KDB staff formally trifurcated its operations in response to the PBB directives. That is, it officially subdivided its operation into three branches for the Kansas Internet Budget and Reporting System (IBARS). The KDB had always operated in such a manner, but the PBB model made it official for budgeting purposes in IBARS. Generally, state agencies use IBARS for purposes of submitting discernable budget requests to the Department of Administration, Division of the Budget (DOB). Agency budget requests, when coupled with an explanatory budget narrative commonly referred to as the DA-400, are then subject to review through the Governor’s Office and Legislature.

When the PBB process was codified, the KDB staff worked closely with highly skilled staff in the DOB to solidify its trifurcated business model in IBARS and the DA-400. As previously noted, the KDB had already been operating in this business model for many years prior to PBB, so the KDB staff simply worked with the DOB to deploy it. The business model is lean because it relies on cost-saving contracts with third-party service providers. Throughout the entire PBB implementation process, the KDB staff remained responsive and engaged with all requests, directives, or suggestions from the DOB. In turn, the DOB accepted the KDB’s submissions as fully complete and compliant with PBB implementation.

Moreover, LPA aptly concluded in the draft report that the PBB statute is general and allows for discretion and interpretation with respect to outcome-based measures. The KDB, as outlined in the draft report, reported output measures. Based on the KDB’s activities, LPA did not think the reported output measures were problematic. Highly summarized, the KDB has definitive metrics that clearly account for, and track, each public dollar that is used for the licensing and regulation of dentists and dental hygienists across the state. The PBB process is successful with respect to the KDB.

Ultimately, PBB appears intended to provide a tracking mechanism for the Executive Branch, Legislative Branch, and Judicial Branch to more easily become and remain transparent with the daily use of highly limited fiscal resources that originate from the hands of the Kansas citizenry. To that end, I remain confident in the application of the PBB model to the KDB.

If you have any questions, please advise. Otherwise, the professionalism, time, and attention of LPA to this matter is greatly appreciated. Thank you.

Sincerely,

B. Lane Hemsley

Executive Director

Appendix A – Cited References

This appendix lists the major publications we relied on for this report.

- Budget Instructions: A Guide for State Agencies, FY 2019 (July, 2017). State of Kansas Division of the Budget.

- Kansas Statewide Efficiency Review (January, 2016). Alvarez & Marsal.

- The State of Kansas Governor’s Budget Report, Fiscal Year 2020, Volume 2 (January, 2019). State of Kansas Division of the Budget.