KPERS: Evaluating the Deferred Retirement Option Program

Introduction

The Legislative Post Audit Committee authorized this audit at its April 8, 2020 meeting to satisfy K.S.A. 46-1136.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following questions:

- How does the deferred retirement option program affect state agencies?

- How does Kansas’ deferred retirement option program compare to similar programs in other public pension plans?

The deferred retirement option program (DROP) is only available to Kansas Highway Patrol (KHP) and Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) employees. We talked to officials from these agencies, the Kansas Public Employees Retirement System (KPERS), and KPERS’ consulting actuarial firm. We also reviewed calendar year 2016-2020 data from all three agencies. We looked at how many staff have joined DROP, how much it costs, and how it affects retirement behavior.

We compared Kansas’ program to 4 similar programs in other states. We also gathered opinions from 5 Kansas employers without access to Kansas’ program.

Finally, we surveyed 111 DROP-eligible current and former KHP and KBI employees to understand how they make retirement decisions. We received 60 responses, about a 54% response rate. The views they expressed are not projectible to other KHP and KBI employees.

We include more specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report confidential or sensitive information we have omitted from this report. We omitted survey responses under K.S.A. 46-1129.

Audit standards also require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. We reviewed controls for ensuring the accuracy of agency data related to employees and their retirement status.

The deferred retirement option program (DROP) appears to help agencies keep experienced staff without significantly increasing costs.

DROP History and Benefits

KPERS administers the Kansas Police and Firemen’s Retirement System (KP&F), which provides retirement benefits to state and local police and firefighters.

- KPERS administers 3 retirement systems, including KP&F. KPERS holds the assets for all these systems in a single, pooled trust. KPERS tracks each system’s assets and liabilities separately.

- KP&F includes 112 participating state and local government employers, such as the Kansas Highway Patrol (KHP), Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI), Salina Fire Department, and Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Office. It covers about 7,500 total police and firefighting personnel, including emergency medical technicians. This includes about 500 KHP troopers, examiners, and officers. It also includes about 70 KBI agents.

- KP&F is a defined benefit plan. A formula determines retirees’ benefits, rather than their contribution totals.

The Legislature created DROP within KP&F to help retain experienced KHP and KBI staff.

- DROP allows retirement-eligible staff to earn their salaries and retirement benefits at the same time. Its goal is to incent these staff to defer retirement for 3 to 5 years. It is currently only available to KHP and KBI employees.

- The Legislature created DROP for KHP in 2015. It opened DROP to KBI employees in 2019. KHP and KBI officials reported staffing shortages prior to DROP. The agencies believed DROP would help them keep experienced, retirement-eligible employees longer. It also gives the agencies more time to recruit and train new staff to replace them.

- The Legislature considered expanding DROP to all 112 KP&F employers during the 2020 session. This legislation did not pass.

- DROP sunsets January 1, 2025. No new participants will be able to join the program after that date unless the Legislature extends it. Active DROP participants will still be able to complete the program.

Retirement-eligible employees can participate in DROP for 3 to 5 years.

- KHP and KBI employees can participate in DROP when they are eligible for retirement. They become eligible based on their age and years of service.

- Tier I includes employees hired prior to July 1, 1989. They are eligible for normal retirement at age 55 with 20 years of service or at any age with 32 years of service.

- Tier II includes employees hired after July 1, 1989. These employees are eligible for normal retirement at age 50 with 25 years of service, age 55 with 20 years of service, or age 60 with 15 years of service.

- Employees stop earning service credits after 36 years.

- DROP participants must decide how long they will take part in the program. They can choose 3, 4, or 5 years. This decision is irrevocable, but any participant may end their DROP after 3 years without consequence. KPERS officials told us KHP and KBI must approve whether and how long their employees take part in DROP.

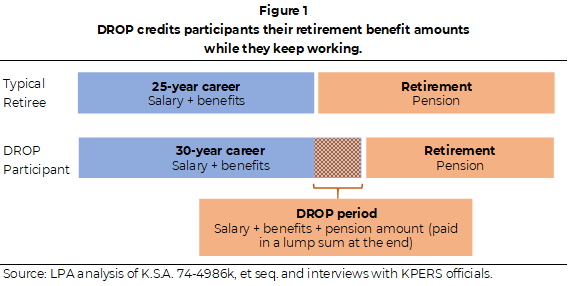

DROP participants’ retirement benefits are credited to accounts while they keep working.

- Once eligible to retire, KHP and KBI staff must decide what to do. They can either retire, keep working outside DROP, or keep working and join DROP.

- If they retire, they stop working. They stop earning their salaries and begin receiving their monthly retirement benefits.

- If they keep working outside DROP, they keep earning their salaries and accruing service credits.

- If they keep working and join DROP, they keep earning their salaries but stop accruing service credits. KPERS credits their monthly retirement benefit amounts to DROP accounts. DROP participants can also earn up to 3% annually in interest. DROP participants who leave before 3 years forfeit their interest. DROP accounts are paid in lump sums at the end of participants’ program periods. Participants can also roll this money over into other retirement accounts.

- DROP participants stop accruing service credits once they enter the program. KPERS uses employees’ service credits to calculate their retirement benefits. KPERS calculates participants’ benefits as of their DROP entry dates and freezes their service credit totals. In this sense, DROP is like retirement.

- DROP participants typically retire when their DROP periods end. Two things happen at this point:

- KPERS distributes participants’ DROP accounts to them in lump sums. Participants can also roll this money over into other retirement accounts.

- KPERS starts paying participants their retirement benefits directly.

DROP’s Current Effects on Participation and Cost

Most KHP and KBI employees we surveyed said DROP has influenced their retirement decision making.

- We surveyed KHP and KBI employees to better understand their DROP and retirement decisions. In all, we sent electronic surveys to 111 DROP-eligible current and former employees. This includes 100 KHP and 11 KBI staff and includes both DROP participants and non-participants. We received 60 responses, a response rate of about 54%. 1 response was incomplete.

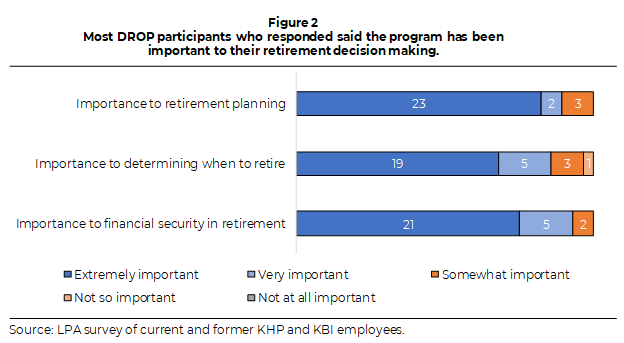

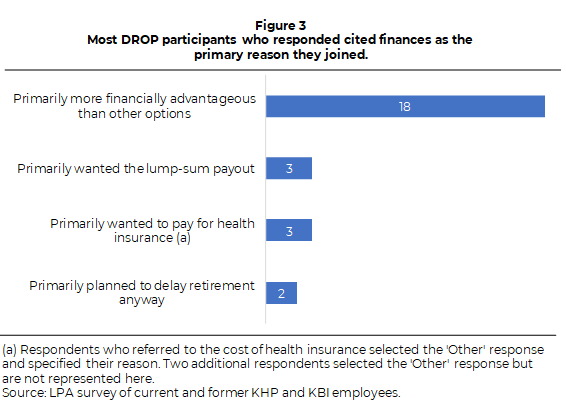

- Of the 60 responses we received, 28 (about 47%) came from DROP participants. This represents about 72% of the 39 staff who had joined DROP by April 2020. As Figure 2 shows, most DROP participants who responded said the program has influenced their decision making.

- Further, as Figure 3 shows, most DROP participants who responded cited finances as the primary reason they joined. Only 2 said they joined primarily because they planned to delay retirement anyway.

- 4 non-participating retirees who responded may have joined DROP under different circumstances. 2 said they were or thought they may have been denied participation by agency leadership. 2 expressed dissatisfaction with their agency’s leadership and not wanting to continue working there.

Current KHP DROP participants will likely retire after working more years on average than non-participants.

- We interviewed KPERS, KHP, and KBI officials and analyzed agency data to evaluate DROP’s current and future impacts. We also talked to officials from KPERS’ consulting actuarial firm. The Legislature gave KHP access to DROP earlier than KBI. KBI only received access in 2019. We had more data on KHP participants. So, we looked further into KHP employees’ DROP and retirement choices.

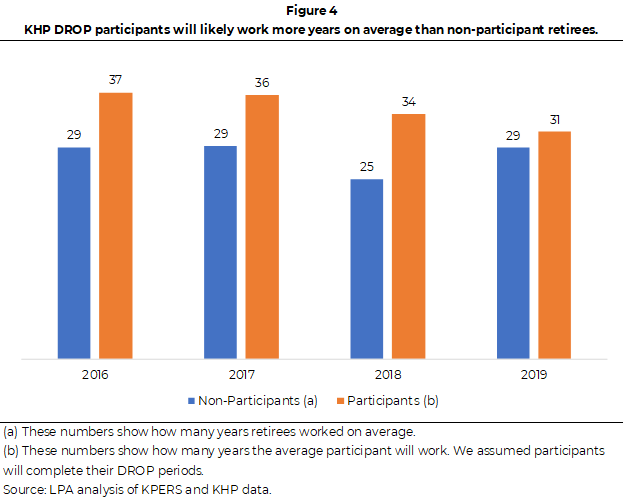

- As Figure 4 shows, current KHP DROP participants will likely work more years on average than non-participant retirees. They will also likely work until more advanced ages on average. This analysis assumes all participants will complete the DROP periods they elected.

- Figure 4 also shows more recent KHP DROP participants are joining the program earlier in their careers. Those who joined DROP in 2019 had fewer average service credits when entering DROP (about 26) than those who joined in 2016 (about 33). By contrast, non-participants have retired at about the same point over this period. The average non-participating KHP retiree had 29 service credits in both 2019 and 2016.

Although KHP DROP participants will work more years on average, the program may not effectively address identified staffing issues.

- KHP officials reported staffing shortages prior to 2015, when the Legislature created DROP. They said they needed more troopers on the road. They also identified 65 understaffed counties. They thought DROP would help address these issues.

- KHP employees ranked lieutenant or below are most likely to engage in front-line law enforcement, such as patrolling highways. Captains and majors are more likely to primarily do administrative or supervisory work.

- DROP may be more effective for retaining higher-ranking administrative staff. Administrators (captains and majors) have disproportionately joined DROP. During 2016-2019, these ranks made up about 14% of KHP retirees but 36% of KHP DROP participants.

- By contrast, front-line staff (lieutenant or below) made up about 83% of KHP retirees but only 64% of KHP DROP participants. Front-line staff such as troopers are proportionally underrepresented.

- Further, DROP may be less effective for retaining staff in understaffed counties. 27 KHP participants were stationed in counties without identified staffing shortages. 8 total participants have come from only 6 of the 65 understaffed counties KHP identified in 2015: Brown, Gray, Kearny, Meade, Neosho, and Osborne counties.

Only 32% of eligible KHP and KBI employees have participated in DROP so far, but more are likely to join.

- 39 of 121 (about 32%) eligible employees had joined DROP as of April 2020. This includes 35 KHP and 4 KBI staff. On average, these staff had 28 years of service when they entered DROP. Current employees who are eligible have 22 years of service on average. Some currently eligible staff will likely join DROP once they accrue more service credits.

- 140 more active staff could become DROP eligible before the program sunsets on January 1, 2025. It is unlikely all 140 will join DROP. About 48 will have service credit totals like current participants’ average service credits. We cannot predict who will join the program, but these 48 staff may be most likely to do so.

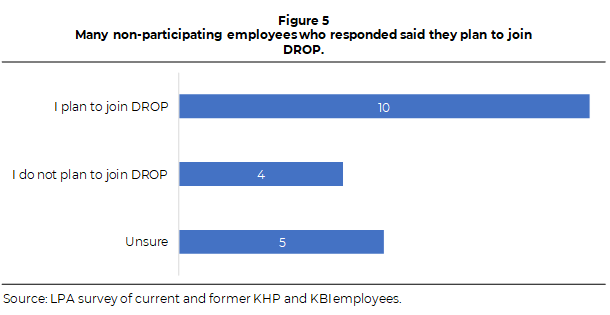

- Further, as Figure 5 shows, 10 currently employed non-participants who responded to our survey said they plan to join the program. 5 more said they are unsure.

KHP, KBI, and KPERS officials told us DROP has not significantly affected their administrative expenses.

- KHP and KBI officials told us they have not had to hire extra staff to administer DROP. Their existing administrative staff have been able to absorb all DROP-related duties.

- KPERS officials told us administering DROP has required about $145,000 in IT work. However, KPERS has not hired extra staff. Two existing staff spend about 10% of their time on the program.

DROP does not create any new staff expenses.

- We reviewed KHP and KBI data to see how employee retirement decisions affect these agencies financially. Based on our analyses, DROP does not create new agency staffing expenses.

- KHP and KBI may pay DROP participants’ salaries 3 to 5 years longer than they otherwise would have. This happens when DROP works as intended and participants defer their retirements. But the agencies would also pay similar amounts to replace staff who retired rather than joined DROP. Related expenses, like training, help offset any differences in salary levels.

- Other factors we looked at appear to have a minimal effect on staff expenses. For example, an agency may promote staff to maintain staffing levels after a retirement. This may create some small short-term costs or savings.

DROP is designed to be cost neutral to the KP&F pension plan.

- Contributions made during DROP help maintain cost neutrality. Participants and their employers pay into KP&F for their entire careers, including during their time in DROP. These contributions help to fund the retirement system and the cost of DROP benefits.

- When DROP works as intended (i.e. an employee joins DROP and retires later than they originally planned), KP&F benefits from longer employee and employer contributions.

- When a participant defers retirement, KP&F receives their contributions longer than it otherwise would have. DROP participants’ contributions would have stopped if they had retired rather than joined DROP. For example, an employee could join DROP or retire after 25 years of service. If they join DROP for 5 years, they will have contributed for 30 years total. If they retire, they will have contributed for only 25 years total.

- Similarly, KP&F receives participants’ employers’ contributions longer than it otherwise would have. DROP participants’ employers would have stopped contributing on their behalf if they had retired rather than joined DROP.

- When DROP does not work as intended (i.e. an employee joins DROP but retires when they originally planned anyway), KPERS’ actuarial liability may increase. Participants who join DROP and retire when they were going to anyway do not spend additional years contributing to KP&F. Neither do their employers. These participants also draw benefits for 3 to 5 years longer than they otherwise would have. KPERS officials told us they do not have enough data yet to say whether DROP is cost neutral overall.

- However, DROP has not affected KPERS’ unfunded actuarial liability. KP&F employers as a group must contribute enough to fund the system’s liabilities. KPERS’ actuaries reassess this each year. They include DROP in their calculations, so KPERS adjusts employer rates to cover the program’s costs. DROP might one day increase what employers pay to support KP&F. KPERS’ actuaries told us DROP has not likely affected this rate significantly.

Potential Effects of DROP Expansion

Allowing all 112 KP&F employers to participate in DROP would likely increase participation significantly.

- 2020 Senate Bill 343 would have expanded DROP eligibility to all 112 KP&F employers, but it did not pass. These 112 employers have about 7,500 total staff. KHP and KBI only have about 565. Expanding DROP to all KP&F employers would significantly increase the number of eligible staff.

- We asked several KP&F employers currently without DROP access about expansion. We selected small and large state and local employers from different parts of Kansas. We talked with officials from the Fort Hays State University Police Department, Kearny County Fire Department, Salina Fire Department, Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Office, and University of Kansas Public Safety Office. For some, we also spoke with budget or human resources officials.

- Most employers told us DROP could be a useful recruiting and retention tool. They said both are difficult. More employers thought it would help with retaining experienced staff than recruiting new staff. That is because new staff are usually young and retirement incentives are typically not relevant to them.

- 1 employer said DROP might help retirees pay for health insurance. KP&F employees often retire before Medicare is available. They must cover their own health insurance costs or find another job. Colorado and Iowa officials we interviewed also cited this benefit. 3 survey respondents said they joined DROP primarily for this reason.

- 1 employer thought DROP would help with succession planning. It would give them firmer retirement dates years in advance. This would help them schedule hiring and promotion testing. Iowa and Omaha officials we interviewed told us about this benefit, too.

- All said they would consider allowing employees to join DROP if the Legislature expanded it. Further, they believed their employees would have interest in an expanded DROP.

- On the other hand, all the employers we interviewed had concerns about the program’s cost. Employers must make larger contributions if DROP increases KP&F’s actuarial liability. KPERS officials told us cost uncertainty is DROP expansion’s biggest drawback.

Expanding DROP could slightly raise agency contribution rates and increase KPERS’ administrative costs.

- KPERS’ consulting actuarial firm estimated how expanding DROP during the 2020 legislative session would have affected KP&F’s actuarial liability. But they said they lacked enough data from KHP and KBI’s DROP experiences to reliably predict how staff would use the program.

- If DROP expansion were to increase KP&F’s actuarial liability, the employer contribution rate would go up. KP&F employers as a group must contribute enough to fund the retirement system’s liabilities. KPERS’ consulting actuaries said they reassess this rate each year.

- The actuaries created 3 expansion scenarios based on how DROP might affect staff retirement decisions. They assumed all staff would make optimal financial decisions. Each scenario estimated an increase in KP&F’s actuarial liability. They would each require a small percentage increase in employer contributions. These ranged from 0.17% if the program works as intended to 1.16% if it does not.

- The actuaries’ scenarios do not increase KPERS’ unfunded actuarial liability. Employers must contribute enough to fund the system as its liabilities go up.

- Finally, KPERS would likely incur some administrative costs from expansion. KPERS officials estimated $65,000 for one-time IT work and $74,000 annually for an extra benefits analyst. We did not review how expansion might affect employers’ administrative costs. Based on KHP and KBI’s experience, these costs may be small.

Kansas’ DROP includes most of the cost neutral elements of the other programs we reviewed.

Kansas’ DROP combines elements of the 4 other programs we reviewed.

- We compared Kansas’ DROP to 4 similar programs in other states. We reviewed other programs’ structures and benefits and selected programs with both similarities and differences. We also considered KPERS officials’ suggestions. We picked 1 program from Colorado, 1 from Iowa, and 2 from Nebraska. This includes the City of Omaha’s program, which KPERS officials identified as the model for Kansas’ program.

- Figure 6 shows how Kansas’ DROP compares to the 4 other programs we reviewed. Certain elements, like service credit caps, come from the retirement systems instead of the programs themselves. But these elements affect how employees use the programs, so we included them.

- Officials from Kansas and some selected programs told us they intend their programs to help retain experienced staff. They have generally similar participant age and service requirements, as well as similar program lengths. Also, all programs except Iowa’s give participants their full retirement benefit amounts right away.

|

Figure 6 Kansas’ and other programs share features meant to achieve cost neutrality. |

|||||

| Colorado | Iowa | Nebraska | Omaha | Kansas | |

| Retirement system funding ratio(a) | 100% | 81% | 87% | 52% | 73% (b) |

| Eligible employer types | Local | Local | State | Local | State |

| Still available to new participants | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Steps taken to help achieve cost neutrality | |||||

| Limits participant interest payments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Allows participation before capping service credits | ✓(c) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Allows employers to deny participation | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Limits participant benefits if they join immediately after becoming eligible | ✓ | ||||

| Participants keep contributing to the retirement system | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Employers keep contributing to the retirement system | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| (a) As of most recent actuarial valuation. Rounded to the nearest whole number. (b) This is 68% for the entire KPERS trust. The trust includes 2 other retirement systems. (c) Colorado’s system does not cap normal retirees’ benefits. Source: LPA review of statutes and program materials and interviews with retirement system officials. |

|||||

Kansas’ DROP aims for cost neutrality like the 4 other programs we reviewed.

- Officials from Kansas and the selected programs said they designed their programs to be cost neutral to their retirement systems. Staff retirement decisions affect whether this occurs.

- All systems limit the amount of interest they pay participants. Colorado officials told us allowing too much interest can hurt a system financially. Colorado and Nebraska participants do not receive interest payments. They invest their own benefits and take on all investment risk. Iowa invests participants’ benefits in certificates of deposit and keeps the interest for the system. Kansas and Omaha credit participants interest based on their systems’ investment returns.

- Most systems require participants and employers to keep contributing to the pension system. Iowa, Kansas, and Omaha require both employee and employer contributions during participants’ DROP periods. Omaha officials said these contributions help ensure a system’s financial health.

- Most systems encourage participants to delay joining the deferred retirement program. KPERS’ consulting actuaries said later retirements cost systems less than earlier retirements. Colorado and Kansas employees become eligible before hitting their service credit caps. Iowa does not pay participants their full benefit amounts if they join immediately. Employees in these states increase their benefits if they wait to join their programs. This may encourage them to join the program and retire later.

- Nebraska officials told us they closed their program to new participants, partially due to cost. Among the programs we reviewed, Nebraska’s differs most from Kansas’. As Figure 6 shows, it has the fewest features for achieving cost neutrality. For example, Nebraska employees become program eligible and hit their service credit caps at once. They do not accrue more service credits and larger benefits if they wait to join. So, most join as early as they can, which increases costs.

KPERS officials cautioned against changing Kansas’ DROP based on other programs at this point.

- Kansas’ DROP already features most of the beneficial elements of the programs we reviewed. We asked KPERS officials about the feasibility and value of a couple potential changes.

- KPERS officials told us initially limiting benefits may be beneficial but unpopular. Iowa officials told us participants must delay joining their program for 2 years after they become eligible to receive their full benefits. They get 52% if they join as soon as they are eligible, limiting the program’s cost to the system. KPERS officials said this change is feasible and could reduce DROP’s cost. However, they thought it would be unpopular and could reduce program participation.

- KPERS officials told us it would not be feasible for participants to make their own investments. Colorado and Nebraska officials said program participants invest their benefits on their own. The system does not pay them interest. KPERS officials said this change would require fundamentally shifting how they do business. It would be costly and would increase KPERS’ workload.

- KPERS officials cautioned against changing how DROP works. They told us they are still collecting data about employee behavior under the current program. Changes like these would disrupt this data collection. This data is important for predicting how people might use DROP if the Legislature expands it to all 112 KP&F employers.

Conclusion

In its current form, DROP costs the state very little and appears to help retain experienced staff. However, the program is also currently limited to a very small number of state employees. As a result, it is difficult to predict the financial impact of significantly expanding the program. Kansas’ program, like those in the other states we reviewed, is designed to be cost neutral. However, our analysis shows that significantly expanding could slightly increase employer contribution levels and result in some additional administrative costs for KPERS.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On July 24, 2020 we provided the draft audit report to the Kansas Public Employees Retirement System, Kansas Highway Patrol, and Kansas Bureau of Investigation. Their responses are below. Agency officials generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.